Ethical safaris in Africa: how some lodges are pushing conservation and ecology over profit, while still offering luxury experiences

- A new generation of luxury safari-goers is choosing holidays based on ecological factors, sustainability and the ability to watch animals without affecting them

- Tour operators are switching to using electric vehicles, listing the carbon footprints of food they serve, building sustainable lodges and offsetting emissions

Big game is not the only game in town nowadays, if you’re heading out on safari in Africa.

Instead, tour operators are talking about “soft tourism”, as nobody wants to be confined to one of dozens of vehicles that are jostling for a brief glimpse of a leopard.

Greater environmental awareness, flight shaming and climate fears have all harmed the reputation of safari mass tourism. These days, lovers of animals in the wild don’t want to see them to their detriment. Indeed, they’d prefer companies to put some of their revenue back into conservation.

Younger safari guests in particular are asking a lot of questions before they book and are increasingly choosing operators based on ecological criteria, says Julie Cheetham, managing director of Weeva, a platform that supports tourism companies in sustainability.

South Africa is a pioneer in eco-safaris, says Cheetham, who sees a major shift in the way people think in the safari sector.

Many safari companies, keen to help guests enjoy nature without hurting what they have come to see, put money into environmental projects, combat poaching and look to offset emissions.

How The North Face co-founder and ex-Patagonia CEO sparked Argentina rewilding

Increasingly popular are eco-safaris, where people stay in sustainable accommodation – lodges made of sustainable materials, rather than colonial-style cement and brick buildings – Cheetham says.

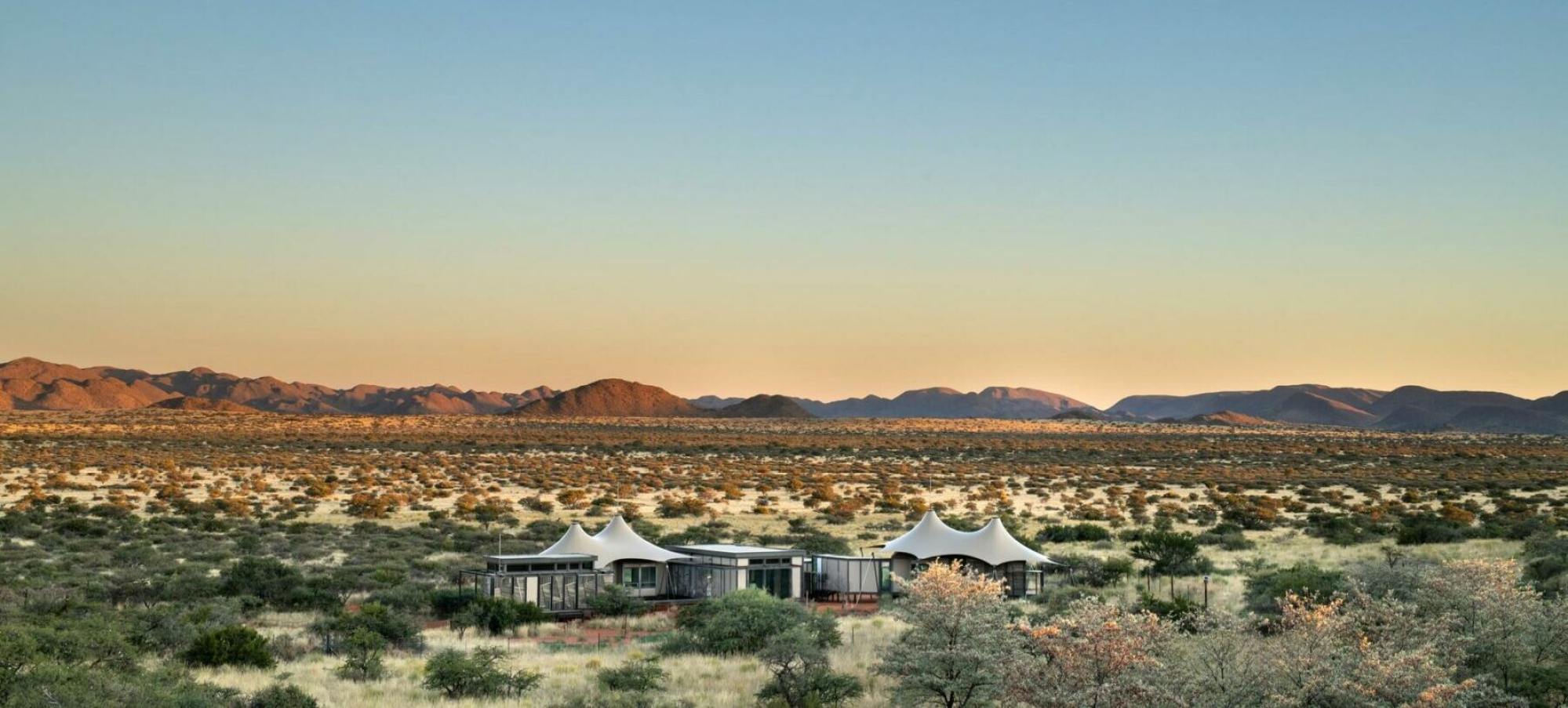

Take the new Loapi Tented Camp, in Tswalu, in the Kalahari Desert, in northern South Africa, which is built mainly from local wood and canvas, stands on stilts and has raised walkways. Small animals and reptiles can find shelter below. And the structure barely affects the soil, says Prince Ngomane, head of sustainability at the Tswalu Foundation.

The camp is powered by solar energy and rainwater is used for showers. There are no plastic bottles or garbage bags, disposable packaging or cling film. The restaurant offers seasonal cuisine using ingredients from local suppliers whenever possible.

Safari operator Singita takes a similar approach with the lodges it runs in Kruger National Park. It did not even lay water pipes underground for Singita Lebombo and Singita Sweni lodges, but neatly hid them below raised walkways.

“The thinking behind it is that the camp could be removed tomorrow and you’d have no idea that once something was there,” says Andrea Ferry, Singita’s sustainability coordinator.

She says Singita does not import building materials or furniture from abroad, which come with a high carbon price tag.

Many eco-safari operators now work out the energy and water consumption of each guest and invest in climate projects to compensate. Options range from reforestation to climate-friendly stoves for impoverished communities – and they also offer guests the chance to offset the carbon emissions of their flights.

That focus has helped Tswalu, a 114,000-hectare (281,700-acre) reserve, become a carbon-positive protected area that offsets more than it emits.

Tswalu is part of The Long Run initiative, founded by German entrepreneur Jochen Zeitz, an alliance of dozens of resorts actively committed to sustainability and conservation.

The reserve sequesters 13.5 tons (13.7 tonnes) of carbon per year, says sustainability manager Ngomane. “We use only about a quarter of what we offset. The rest remains as a carbon positive reserve.”

Other eco-providers, including Singita, also promise guests a carbon-neutral stay, or document their focus on sustainability. Some eco-lodges list the carbon footprint of individual dishes, for example, says Cheetham.

Electric mobility also has its place in this green new world. Solar-powered luxury lodge Cheetah Plains, in South Africa’s Kruger Park, uses e-vehicles with solar-charged batteries.

No more vandalism, urine bottles: world’s largest Buddhist temple is reborn

That saves a lot of exhaust gas, says marketing manager Peter Dros, as each safari vehicle in the private reserve covers around 32,000km (19,800 miles) a year.

Furthermore, e-cars are quiet, so guests are better able to hear the sounds of birds and wildlife, Dros says.

As with Tswalu, Cheetah Plains also has a negative carbon footprint. Anyone who spends three nights here automatically offsets their international flight, he claims.

Many other lodges are testing e-terrain vehicles, but e-driving presents some challenges, as safaris can involve distances farther than batteries can cover.

There aren’t many charging stations in the middle of the savannah, says Cheetham. Plus, dust and sand can be a problem for electric motors.

Tswalu started out by buying four smaller conventional safari vehicles, which at least consume less fuel.

Other options are going out on foot, horseback or bicycle – all options people want, says Cheetham. Guests, no longer protected by a vehicle, instead rely all the more on experienced rangers, who carry loaded rifles in case of an emergency.

“A walking safari gives you a totally different perspective of the wilderness. Suddenly, you are right in the middle,” says Ngomane.

The industry used to focus far more on profits. Suppliers exploited nature without a thought for the long-term consequences.

It is the tourists who are driving the change, as, for many, climate is the key factor when it comes to making a booking, says Cheetham.

The Londolozi Lodge, in the Sabi Sands Game Reserve in South Africa’s northeast, reinvests a fixed percentage of its annual revenue in conservation. For every night they stay, each guest indirectly pays for the protection of six rhinos, helps send eight children to school and trains one adult, the website says.

Tswalu is a prime example of eco-safaris. In 2021, the reserve’s owners spent 86 per cent of their total investment on conservation, habitat rehabilitation and anti-poaching efforts.

Tswalu is also home to a climate-change research project involving scientists from universities across South Africa.

Lepogo Lodges, in South Africa’s Limpopo province, goes a step further as a not-for-profit company that ploughs 100 per cent of its earnings back into conservation, it says.

Named after the Sotho word for cheetah, Lepogo focuses on reintroducing and protecting that particular species of big cat. It also runs conservation projects for endangered roan antelope, white and black rhino, and Cape buffalo.

“Because a safari product is essentially nature, it makes complete sense that they are the front runners in conservation,” says Ferry.