How India’s abortion laws are trailing society, technology and the young single women having more sex

Faced with a 20-week limit and cultural and other legal restrictions, millions of Indian women have abortions outside hospitals and clinics, while many others do not even know the procedure is legal because of a lack of public education

Using euphemisms, Anita Adhikari, 43, says shyly that her husband wants sexual intercourse almost every day. How they manage to perform the act is a mystery. The chip board partition which separates her room in a slum in Gurgaon, a satellite city of the capital New Delhi, from the family next door is so flimsy you can hear her neighbours talking.

With two grown-up married children, Anita is far less interested in sex than her husband, but she has no choice in the matter. Like most Indian women, she has to obey his every whim.

Pregnancy problems leading cause of death for teenaged girls and young women worldwide, study finds

Anaemic and underweight, Adhkari used to miss her periods occasionally. When there was no sign of her period after three months, she assumed her menopause had started. But, feeling anxious one day in February, she went to a doctor who said she was pregnant. She went to a nearby chemist and bought an abortion pill. By now, she was in her 18th week. The pill did not work. The only option was a surgical abortion.

In India, a woman cannot have an abortion simply because she does not want the child. The idea of “choice” is missing from the law.

Adhikari’s family is complete. Her children are in their late 20s. Her son is about to become a father. “The last thing I wanted at this stage of my life, when I’m about to become a grandmother, is another child. And I just don’t have the money,” she says.

Her doctor refused to arrange an abortion, which can only be performed up to 20 weeks from conception. By now, Adhkari was 22 weeks’ pregnant. If a woman wants to abort her fetus after the 20-week limit, a doctor can perform it only on three grounds: that the pregnancy poses a risk to her life; that the fetus has a severe abnormality; or that the pregnancy is the result of rape. Moreover, if the pregnancy is between 12 and 20 weeks, not one, but two, doctors have to sign off on it.

Adhikari cannot simply choose not to be a mother because she doesn’t want a child, or because she cannot afford to raise it, or because she is unhappily married, or because she does not want to complicate an already difficult life. Like millions of other women, she was in a fix. Where and how could she get an abortion?

“It was very frightening. My pregnancy was advancing and I felt time was running out,” she says.

Indian lawmakers had good intentions at the time they agreed to a 20-week time frame. Based on medical knowledge at the time, they felt that an abortion beyond 20 weeks would be unsafe. Even at 12 weeks, it was considered unwise. So they protected women by ensuring that two doctors had to sign off on an abortion if it was to happen between 12 and 20 weeks.

But the law, passed in 1972, has worked against women who discover abnormalities or develop complications, or who simply discover they are pregnant very late. And it is out of date; advances in technology have made it possible to detect fetal abnormalities – or risks to the mother – after the 20-week limit. In these cases, Indian women must get a court’s approval for an abortion. Clogged with pending cases, the courts take a long time to reach a decision, and often the approval comes after the legal limit.

Last year, a 14-year-old girl from Uttar Pradesh who became pregnant after being raped went to court after she was denied an abortion. The proceedings took eight weeks. By that time, her pregnancy was far too advanced. Having failed to get an abortion, her family forced her to marry her rapist to save the family from the “dishonour” of an unmarried pregnant girl.

The difficulty of getting a legal abortion pushes millions of women either into having abortions outside a proper hospital or clinic or into buying over-the-counter abortion pills. The findings of a study by the Guttmacher Institute published in December in The Lancet show that of the 15.6 million abortions carried out in 2015, only 3.4 million (22 per cent) took place in health facilities.

It’s been a nightmare. I was terrified the doctor would tell my family or that they would find out somehow

Faced with the 20-week limit, millions of women, rural and urban, end up seeking the help of quacks working in insanitary conditions. A total of 11.5 million or 73 per cent of abortions were obtained outside medical facilities through medication and another 800,000 (5 per cent) were through “other” methods that were probably unsafe.

As a poor, illiterate woman who works in a tyre factory, it was out of the question for Adhikari to go to court to obtain permission for a legal abortion. Even if she had the money, how could she prove the pregnancy was a risk to her life or that the fetus had an abnormality? Neither was the case. Eventually, an aunt took her to an unauthorised clinic for an abortion.

China’s one-child policy has a legacy of bereaved parents facing humiliation and despair

Many gynaecologists and women’s rights activists believe the law needs to be amended. “The limit definitely needs to be extended to 24 weeks, because medical advancements have ensured that it is perfectly safe and ethically sound to terminate pregnancies at that stage,” says Dr Jaideep Tank, secretary general of the Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India.

In fact, an amended bill has been ready since 2014. It proposes several changes to bring the law up to date, medically and culturally. These include increasing the legal limit from 20 to 24 weeks and recognising that the right to safe and legal abortion is every woman’s right, not just that of married women.

Indian society has changed drastically over the past few decades. Single women are more sexually active than before. Many women are divorced, single or in a live-in relationship.

Natasha Puri, for example, was studying journalism in New Delhi and had a boyfriend. They had been sleeping together for a few months when she discovered she was pregnant last November. “Having a baby was out of the question. I wasn’t even very serious about him. I had to study and do something with my life,” Puri says.

After taking an abortion pill, she started bleeding heavily and running a high temperature. When she went to the doctor and told him she was pregnant, the first thing he asked was: “Are you married?” She lied: “My husband is out of town on business.”

After examining her, the doctor said she had had an incomplete termination and that an infection had set in. She went in for surgical evacuation, without telling her boyfriend or her family. “If they knew, they would never speak to me again,” she says. “It’s been a nightmare. I was terrified the doctor would tell my family or that they would find out somehow.”

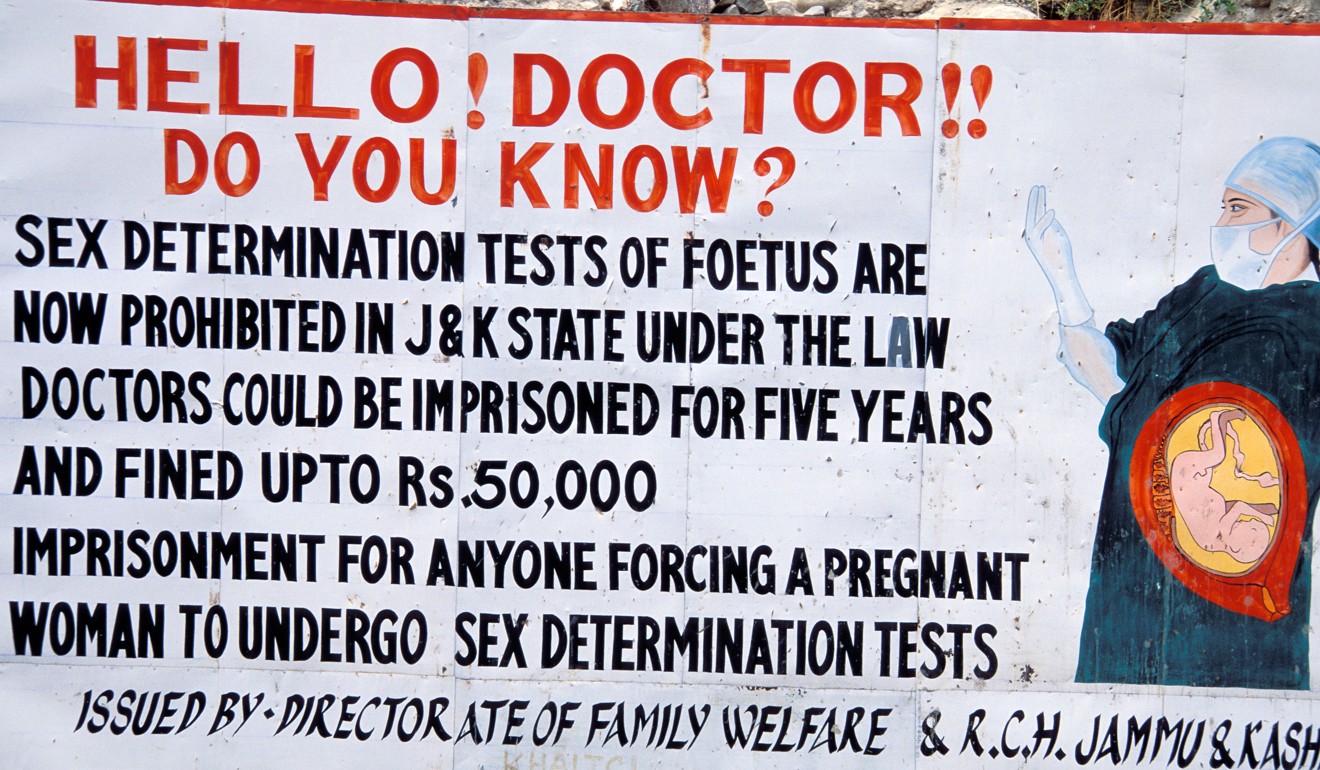

The government’s campaign against sex determination to protect the girl child has got horribly confused in women’s minds with abortion

Single women like Puri are particularly vulnerable. Not only can they not talk to their family, but they also lack the support of a partner. The fear of a doctor telling their parents or word getting out delays the process of seeking medical help.

Puri is an educated woman living and studying in the Indian capital. She knew that abortion was legal and knew what to do. But, as Dr Manisha Gupte, a pioneer in advocating abortion rights for women, points out, the vast majority of rural women do not know that abortion is legal.

“Since a woman’s right to control her reproduction was not the basis on which the law was formulated, no government ever launched a public campaign to make women aware of their right,” she says.

Most rural women think that seeking an abortion is a crime, so they are scared to ask about getting one – which is why many wait too long, and exceed the 20-week limit when it does become illegal.

“The government’s campaign against sex determination to protect the girl child has got horribly confused in women’s minds with abortion,” Gupte says. “The ads against sex determination say, ‘Mummy, don’t kill me,’ they show splattered blood, or a noose around a fetus. This emotional tone makes women think an abortion is both a crime and a sin.”

Meet the Gulabi Gang: stick-wielding women vigilantes standing up to abusers in India

The amended abortion bill will make it possible for young unmarried women like Puri to get an abortion without having to pretend they are married. But four years have passed and the Prime Minister’s office is still mulling it over.

“It’s not a priority for male MPs,” Gupte says. “In this patriarchal society, men don’t like the idea of women having control over their bodies. Who knows – they might deny them an heir. And it’s not important for them because men don’t get pregnant.”

Some names have been changed to protect people’s identity.