She wants to make pineapple buns as popular as ramen: how Ho Yuen Cafe brings a little bit of Hong Kong’s Lion Rock spirit to Canada

- In Vancouver, Canada, a Hong Kong-style cafe offers former Hongkongers a taste of home – think barbecue pork, pineapple buns, instant noodles and egg tarts

- Its owner has the DNA to run a cha chaan teng – her father opened one in Hong Kong in the 1960s and brought it to Canada in the 1980s. She continues his legacy

Inside Ho Yuen Cafe in Vancouver, Canada, hangs a painting.

The image is that of Hong Kong’s Lion Rock mountain nestled between Hong Kong’s and Vancouver’s cityscapes – an illustration of how the “Lion Rock spirit” links the newly opened cha chaan teng with its original in Hong Kong.

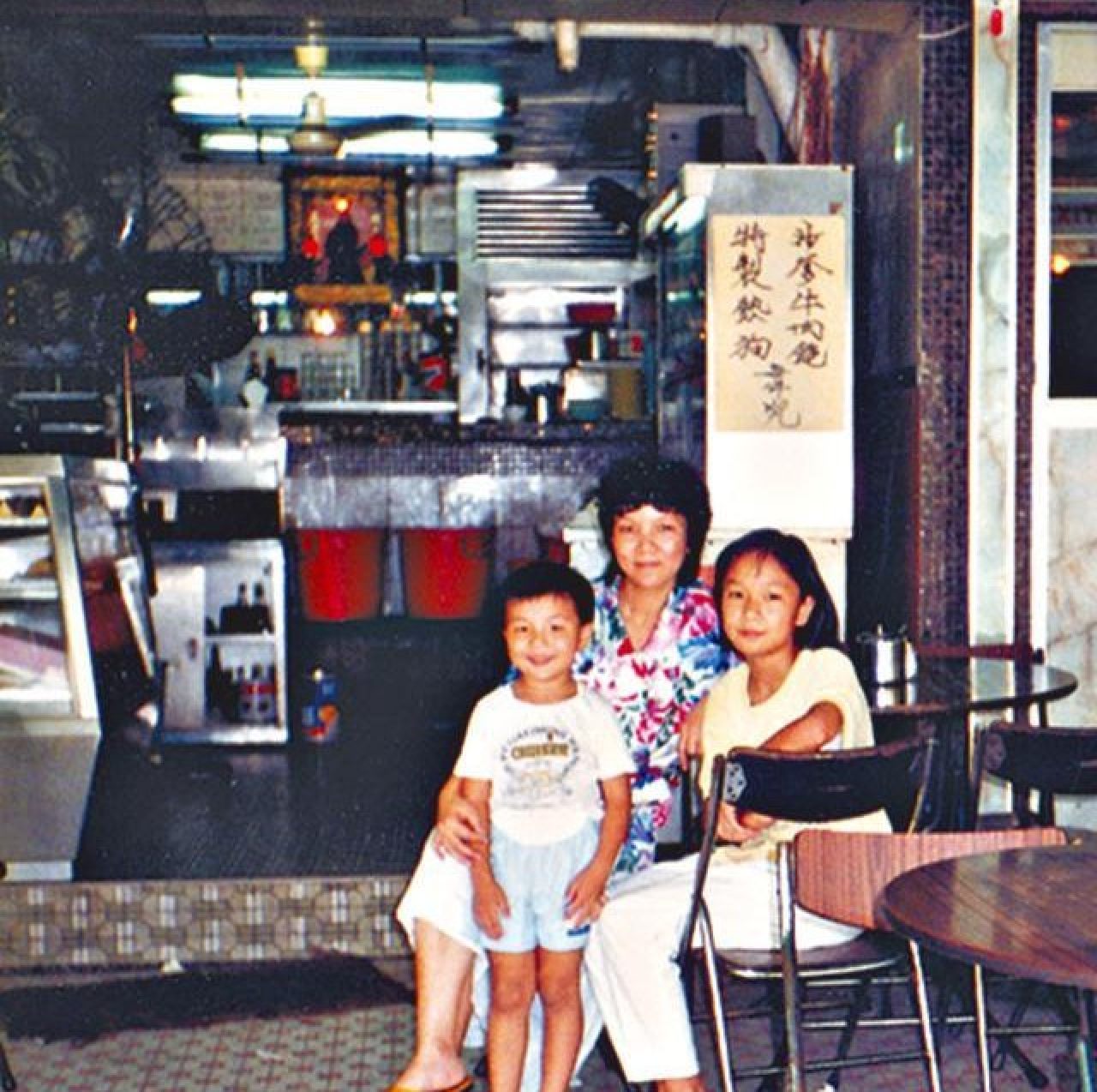

Conina Mui Lok-man is the second-generation owner of Ho Yuen, the first of which was established by her father in Hong Kong in the 1960s.

Mui remembers helping her father at the restaurant as a child, then later manning the cash register and working in the kitchen.

She was also on hand to help when the family moved to Vancouver in the 1980s, when her dad opened Ho Yuen and Ho Yuen Noodles.

The family returned to Hong Kong in 1996 after her father retired.

After graduating from university with a degree in marketing, Mui started working in the fitness industry, where she met fitness trainer Taro Lim, who eventually became her husband. He now roasts barbecue pork in Ho Yuen Cafe, and the two have a son together.

Mui never thought she would return to the restaurant industry but, in 2014, she saw an opportunity to start something new in her neighbourhood.

“I like eating cha chaan teng food, and it just so happens when I moved to Wong Tai Sin [in East Kowloon], there was no cha chaan teng and there was a shop for lease,” she says. “My father thought the space was good and he inspired me. It’s all about timing, the right place and meeting the right people. I just follow the flow.”

“We had regular meetings with the government to … see who would get which location, and everyone wanted Disneyland because we could make money there because it was a tourist area,” she recalls.

“Every day we had to load up food, figure out parking and where we could get electricity and water, and create new menus every two weeks because we couldn’t sell the same food at Disneyland as Kwun Tong pier,” says Mui. After the day was over, they had to clean up, and remove the food that was not used.

Even though the scheme was not profitable, Mui was happy to see the public get reacquainted with the Ho Yuen brand and says she learned a lot from the experience. “We had to be very flexible and quickly adapt to different situations.”

Mui chose to move back to Vancouver in 2020 for her son, who has special needs. She also wanted to open a place that would give her a better work-life balance – it is why the cafe’s hours are Mondays to Saturdays, from 9am to 4pm.

Mui says she took her time to find a space in Vancouver. “Buying a restaurant here is very expensive. I’m in marketing, so I’m curious and like to look around and explore. When I saw this space, I really liked it. It reminded me of our shop in Wong Tai Sin.”

Chinese restaurants tend to have extensive menus, which means a lot of work for the kitchen staff and high food costs. Mui went with a menu with only a few items to maintain quality. It has worked – the feedback from customers is that the pineapple buns and satay beef noodles have the same flavour as the ones in Hong Kong.

Mui is pleased because recreating the same flavour has been a challenge. This has been particularly so for baked goods, as Canada’s protectionist policies prevent the cafe from importing the flour used in Hong Kong. Instead, they had to experiment with many different kinds of Canadian flour.

Mui wants to continue spreading her passion for cha chaan teng culture across North America – specifically the west coast, from Vancouver down to the United States.

“Our target market is not Chinese people,” Mui says. “Our long-term goal is to introduce pineapple buns, milk tea, satay beef noodles – like how everyone knows [what] Japanese ramen [is].”

As if on cue during our interview, a young Caucasian man comes into the shop to buy some pineapple buns.