How US schools use locked wooden box puzzle to motivate students

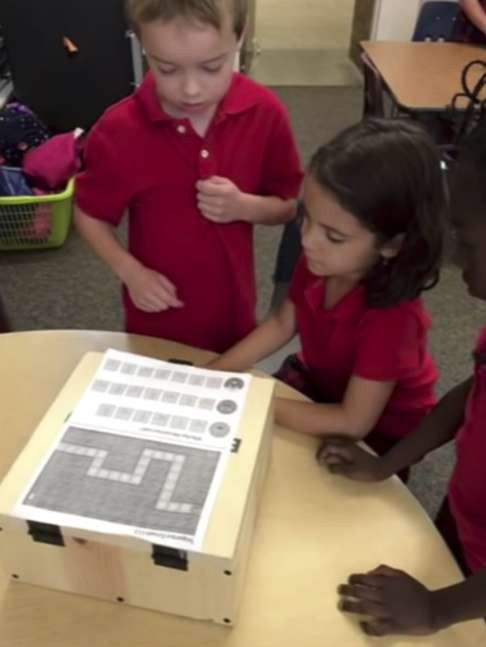

Created by a San Francisco-based start-up, Breakout EDU takes the idea of ‘escape rooms’ and flips it inside out – forcing students to use teamwork, problem-solving and critical thinking to open a locked box

One of the most talked-about education tech innovations in the US this summer is not so hi-tech. Actually, it is mostly wood-based.

Occupying a school bus parked outside the annual conference of the International Society for Technology in Education recently, a tiny start-up called Breakout EDU generated waiting lines as teachers queued up to get a peek.

How Hong Kong designers help children with special needs cope with school and learn better

The company is based in California, though its chief executive, Adam Bellow, lives in New York. At its simplest, Breakout EDU takes the appeal of the “escape room”, a recreational team sport in which a group of people use their wits to break out of a locked room, and turns it inside out.

The wooden models go for US$119 (about HK$920) plus shipping, but demand has been so high that the company recently contracted for a compact, black plastic model resembling a tiny suitcase.

“We’re all educators on the team, so the educators in all of us say, ‘We’re never going to be billionaires from this.’”

The company wants to impact teaching at a basic level, making it more problem-based, more social, more interactive and more physical. “I have little kids,” Bellow says. “When I see them doing this in their class, that is what I want for their education.”

A former Presidential Innovation fellow at the White House (as is co-founder James Sanders), Bellow saw the Breakout EDU model at a professional development event for teachers in Baltimore in March 2015. “I said, ‘This is it. This is lightning in a bottle.’”

Sanders has said he got the idea after visiting an escape room in Canada with a group of high school students. “I’d never seen high school students work that hard in my life,” he told Education Week last year.

He and his colleagues began prototyping lock boxes and building them in co-founder Mark Hammons’ garage, not unlike how many other tech start-ups took shape.

Since its inception last year, the company has invited teachers to develop their own games built around the boxes. Teachers have stepped forward with hundreds of games on nearly every topic, from environmental science and Advanced Placement physics to kindergarten-level literacy. More than 200 are available for free on the company’s site, and though it gives teachers the option of charging one another for them, none of the teachers has asked for payment.

“It’s one of those things that, once they do it, they get hooked,” Bellow says.

In one game, players must complete a computer coding unit that reveals a QR code that takes them to an internet site that helps solve a puzzle that unlocks a combination … that gets them into the box.

That tracks with bedrock “intrinsic motivation” research that suggests the way to motivate people to work hard is to give them challenging tasks that they can figure out for themselves while making them feel competent and connected.

“There are cheers, there’s frustration, and ultimately, if there is success, it’s that moment of ‘We did it!’ And that is intrinsic. It doesn’t need something else,” he explains. “I don’t see kids cheering when they do worksheets.”

The game-like lessons, Bellow says, are a welcome relief from the “canned curriculum” that teachers often rely upon.

The company won’t give out sales figures, other than to say it has sold “in the low thousands” of boxes. They’ve found that schools will often buy one box, then, within a few weeks, five more, “because the reality is that it’s an idea that works”.

Bellow estimates that there are about 8,000 teacher members who are “extremely active” in Breakout EDU’s online community, sharing lessons on Facebook and posting instructions to YouTube. To prevent students from simply searching online for instructions, the games themselves can’t be accessed except with a password.

Once a school purchases the kit, teachers and students don’t need to buy anything extra. They can simply modify the hardware to suit what they want to teach.

“We look at ourselves as the platform,” Bellow says. “We are Nintendo – you build whatever cartridges you want.”