How Hong Kong New Wave cinema classics Nomad and The Story of Woo Viet, early movies by Patrick Tam and Ann Hui, show the movement’s diversity

- Hong Kong New Wave cinema legends Patrick Tam and Ann Hui’s early films Nomad and The Story of Woo Viet are very different

- Starring Leslie Cheung, Tam’s film played with genres. Hui’s film, with Chow Yun-fat, addressed social issues. Together they show the range of the movement

Hong Kong New Wave film directors Patrick Tam Ka-ming and Ann Hui On-wah both began their careers making programmes at Hong Kong broadcaster TVB, and Hui looked to the more experienced Tam as a mentor.

But they made very different types of films. Tam followed an interest in expanding the style of Hong Kong movies, while Hui made more straightforward films which highlighted social issues.

Nomad (1982)

While not as daring as the latter movie, a stylistic experiment with colour that limited its palette to red, white and blue, Nomad took a then-unusual approach by switching from a character-based story about youthful ennui to a thriller involving Japanese terrorists.

The time Michelle Yeoh stepped away and Cynthia Khan stepped in

The film is also notable for its natural and healthy depiction of sexuality – especially from a female point of view – at a time when most scenes of sex displayed on Hong Kong screens were of the comic nudge-nudge, wink-wink variety, or depicted violence against women.

“It was a film of vast complexity,” critic Law Kar wrote in his essay “The Progress and Contribution of Patrick Tam”. “It is one of the most important films of Tam’s career, and of Hong Kong in the 1980s, for its new sensibility and its conflicting attitudes towards popular/youth culture and modernisation.”

At the time of its release, Nomad was criticised for its depiction of urban youth, especially the unbridled sexuality of the character played by Pat Ha, who even makes love on the back seat of a moving tram.

The censors ordered some cuts to be made when a head teacher complained after seeing the film at a midnight preview.

The story begins with a focus on two romances that cross the class barrier.

Listless and irritable, the quartet dream of a life away from their urban woes, and fantasise about a free and easy existence – symbolised by the Nomad, a swish yacht belonging to Louis’ father.

The film handles the problems arising from their relationships with panache, but shifts gear when it transpires that Kathy’s time in Japan was spent with a terrorist boyfriend from the Japanese Red Army.

When he absconds from the terrorist group and turns up in Hong Kong to hide out on the Nomad, the film morphs into a violent thriller.

In an interview with critic Alberto Pezzotta for his book From the Heart of The New Wave, Tam said he was asked by producer Jeff Lau Chun-wai to make a youth movie, but expanded that idea.

“The one I wanted to make was different, in that it was not meant to be a realistic portrait. It would depict a more conceptual dimension. I was reading [philosophers] Friedrich Nietzsche and Gilles Deleuze and I liked the idea of ‘Nomad thought’, the idea of exploring the unknown,” he said.

The Sword, Patrick Tam’s modern twist on the martial arts hero

“I hoped I could make my characters embody this idea. I wished to explore the youthful energy which can be found in any age, if only the wish to explore and go far with their vital energy.”

The ending of Nomad, a poorly staged samurai swordfight on a beach in front of the boat, has confounded many critics, especially as it includes a leap using wires that’s better suited to a wuxia film.

Tam says that his original idea for the ending was hampered by “technical difficulties” and the scene was actually shot by producer Dennis Yu Wan-kwong.

“This is not the original meaning that I wanted to give the ending, [which was that] the ship does not stop even after the massacre – the spirit of freedom cannot be stopped by any kind of violence,” Tam said.

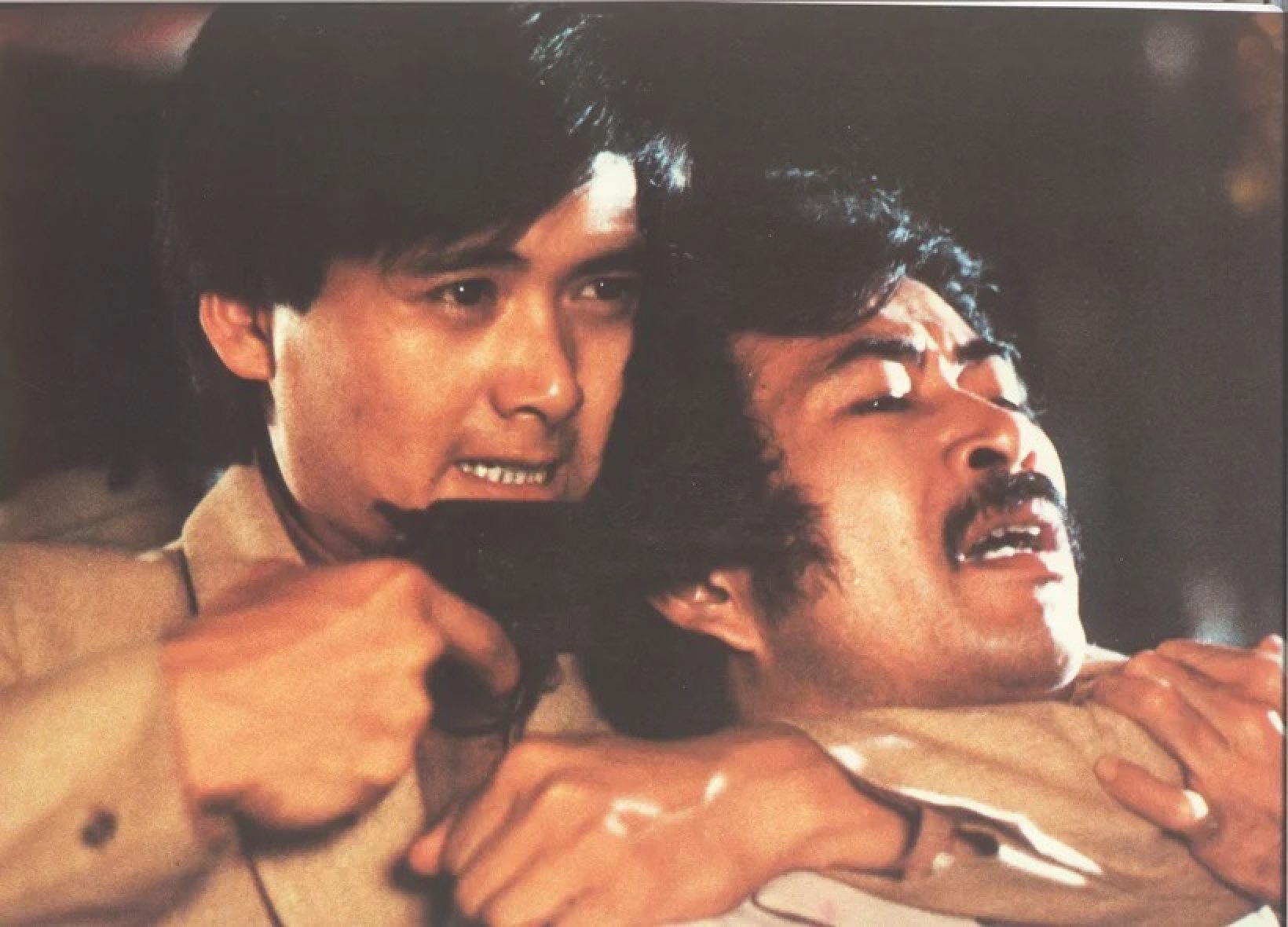

The Story of Woo Viet (1981)

Unlike Tam, Hui at this time was not interested in exploring film language, preferring instead to focus on presenting a clear exposition of social issues, often marrying them to elements of a crime thriller to give the story form and make the ideas accessible.

“I really want to do something different but I will not do it purposely to show off my own style and techniques,” she said in an interview at the time. “The themes of Hong Kong movies must enrich the viewers who have been numbed by senseless kung fu jabs.”

One reading of Woo Viet – and the trilogy – is that it uses the milieu to comment on Hong Kong’s relationship with Communist China. But Hui has always denied she was making a political comment. “I wasn’t doing that – people have read that into it,” she told this journalist in 1998.

To rescue her, Woo Viet has to agree to kill for the gang.

The film looks realistic, as Hui shot most of it in Manila. “It was very hurried,” she told this journalist. “There were a lot of brownouts in the city – it was a very chaotic place.

“That actually made it easier, as we didn’t have to inform the police about where we were shooting. We filmed in Chinatown, in real massage parlours and places that were supposed to be impossible to film in,” she said.

Film director Ann Hui on her Venice lifetime achievement award

Hui had not planned to make a second film about Vietnam. “When I worked at RTHK, I researched stories about Vietnamese refugees. Based on that research, I wrote Woo Viet,” she said.

“I had other material for films, but it just so happened that the investors chose Woo Viet. The next time, the investors chose Boat People. So it just so happened that I shot these two films about the Vietnamese.”

Although Woo Viet does not shrink from portraying the hardships of the boatpeople as they try to make their way to Hong Kong, it also works as a taut crime thriller.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.