Explainer | Who led cinema’s Hong Kong New Wave? The directors, from Tsui Hark to Ann Hui, their movies and how they changed filmmaking in the city

- A new breed of filmmakers who wanted more than kung fu movies emerged in the 1970s after Bruce Lee’s death, and forever changed the Hong Kong film industry

- We recall the Hong Kong New Wave’s big players, from Patrick Tam to Ann Hui and Tsui Hark, their roots in television and focus on modern techniques and subjects

The Hong Kong New Wave of the late 1970s and early 1980s is spoken about with reverence today. We look at the directors and the films that changed the course of filmmaking in the city.

What exactly was the Hong Kong New Wave?

In a nutshell, it was a group of young filmmakers with new ideas and modern techniques who brought Hong Kong films up to international standards in terms of production values and stories.

“In the mid-1970s, the ranks of film and television were joined by a number of filmmakers who eventually changed Hong Kong films,” wrote influential critic Law Kar in his book Hong Kong Cinema: A Cross-Cultural View.

“Determined to use modernised cinematic language, they managed to update a film industry that had been mired in increasingly archaic ways,” wrote Law, who once worked alongside filmmakers like Hui at Hong Kong broadcasting company TVB.

How filming Hard Target taught John Woo some hard lessons about Hollywood

What was different about their work?

By contrast, the New Wave filmmakers brought a distinctly European art-house flavour to their works, and generally favoured social topics, although they made many other types of film.

Many of the young filmmakers had studied abroad, where they learned up-to-date filmmaking techniques which they brought back to Hong Kong.

“They were concerned with visual style and had stringent demands for photography, art design, sound effects and music. Preferring small, mobile crews, they went on location all over the territory, leaving the stodgy ways of studio sound stages behind them,” Law wrote.

The New Wave directors wanted to experiment and change the way Hong Kong films were conceived and shot.

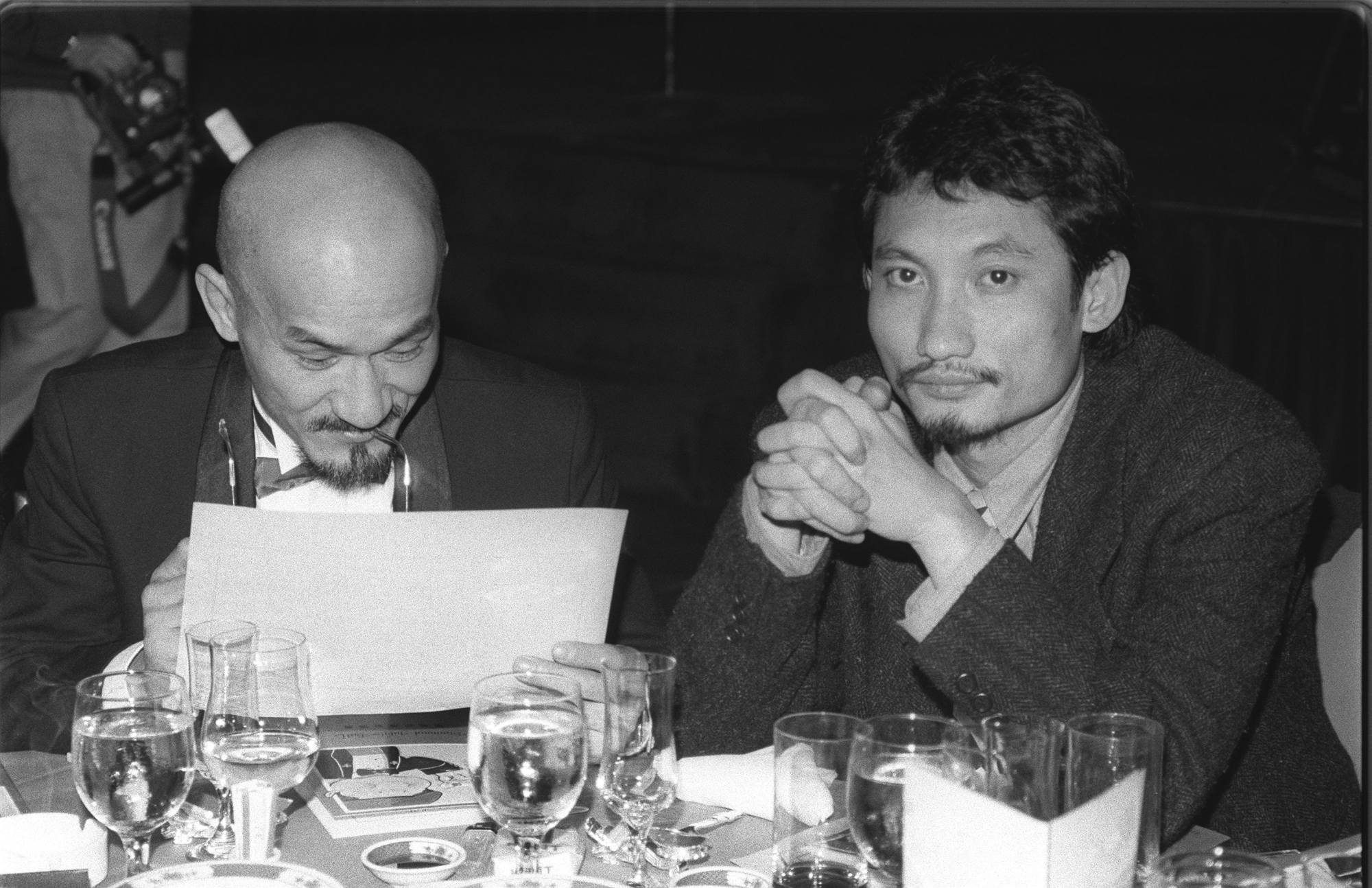

“[The aim] is to establish a new film language. A custom-made film language for Hong Kong or even mainland China,” Patrick Tam told the Chinese-language magazine Film Biweekly, in 1979.

It was a group effort, noted Tam. “I don’t think this is the sole responsibility of one person like me. Each New Wave director should keep exploring new tools and new ideas to keep creating,” Tam said.

Is it true that many directors began their careers in television?

Yes, and it was an effective way for them to hone both their technical and storytelling skills.

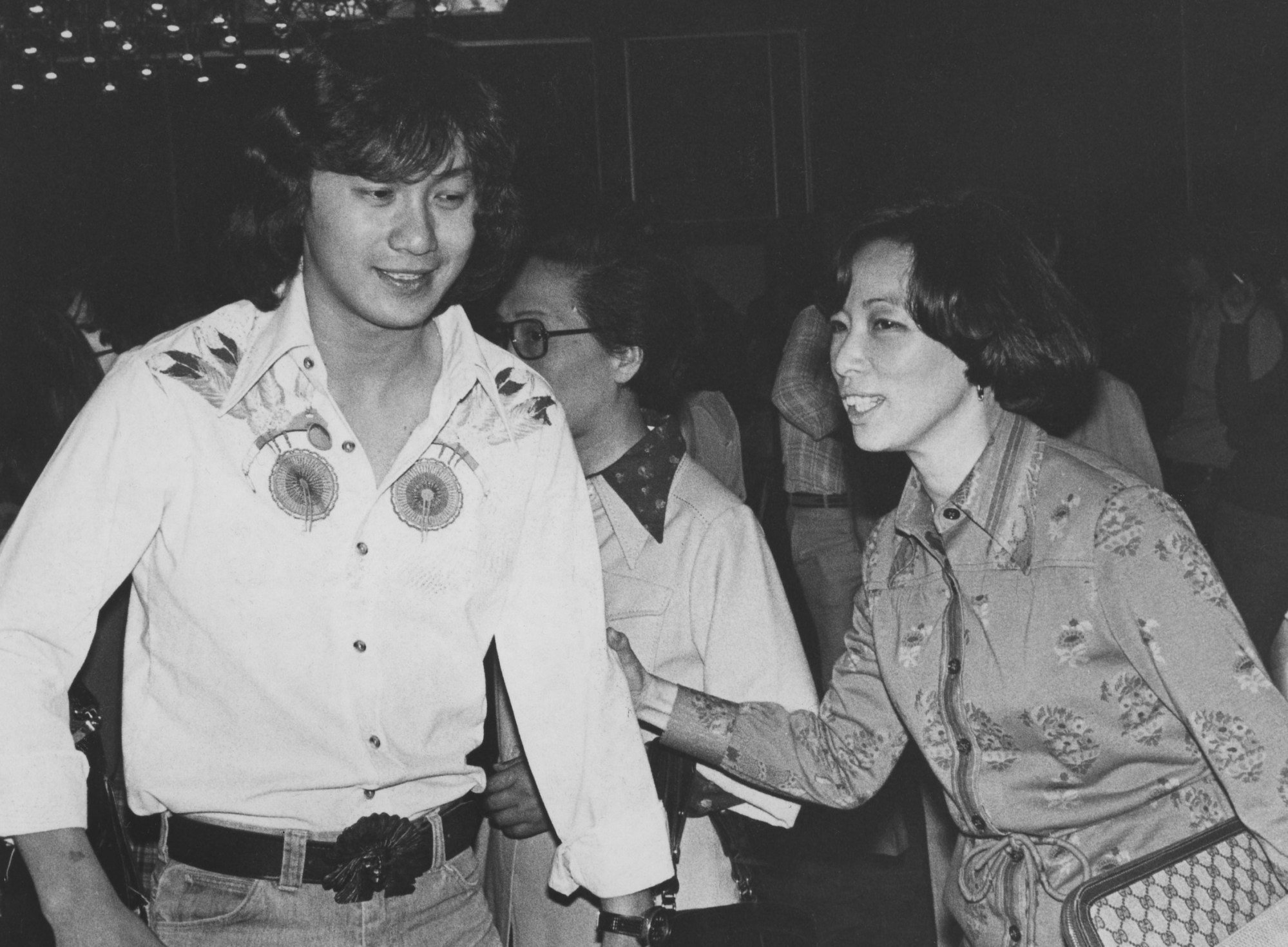

Novice directors like Tam, Ann Hui and Tsui Hark, among others, were invited by Selina Chow Liang Shuk-yee, TVB’s head of production, to work at the station.

Chow courageously gave her new employees much creative freedom – the directors had almost complete control, and could go ahead and make a TV film from a short news story or even just a title.

The 10 best films of Ann Hui, Hong Kong’s most celebrated director

“[The TVB executives] never read our scripts,” Hui told film programmer Tim Youngs. “It was really up to us. They didn’t read the stories and they didn’t ask to watch the episodes before they aired. I think they were too busy and trusted us to do our best.”

The results were stunningly good, and led to what critic and filmmaker Shu Kei has called “the Golden Age of Hong Kong TV”.

Ann Hui did important work for television, didn’t she?

Hui was a tireless TV director whose large body of television work is well respected. She worked on numerous episodes of a series called C.I.D. at TVB, a programme which used detectives to link together socially relevant crime stories about murder, abortion, suicide, and so on.

Hui was then hired to make TV films for Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) – she made dramatisations of real-life ICAC cases.

What are some of the important New Wave films?

Hong Kong film exhibitors demand a lot of film product, and the New Wavers were used to working fast for their television jobs. Put that together and you get a lot of films to choose from.

Fong’s Ah Ying, about a young girl in Hong Kong who tries to forge a path through life via self-education, won both awards the year after, and was notable for using non-professional actors who told their own stories on camera.

Yim Ho’s Homecoming, about a Hong Kong woman who returns to a small village in China, won best film and best director at the HKFA in 1984.

Tam’s Love Massacre and Nomad are also significant, as are Tsui’s early works.

I keep hearing about Leong Po-chih’s 1976 film Jumping Ash. What about it?

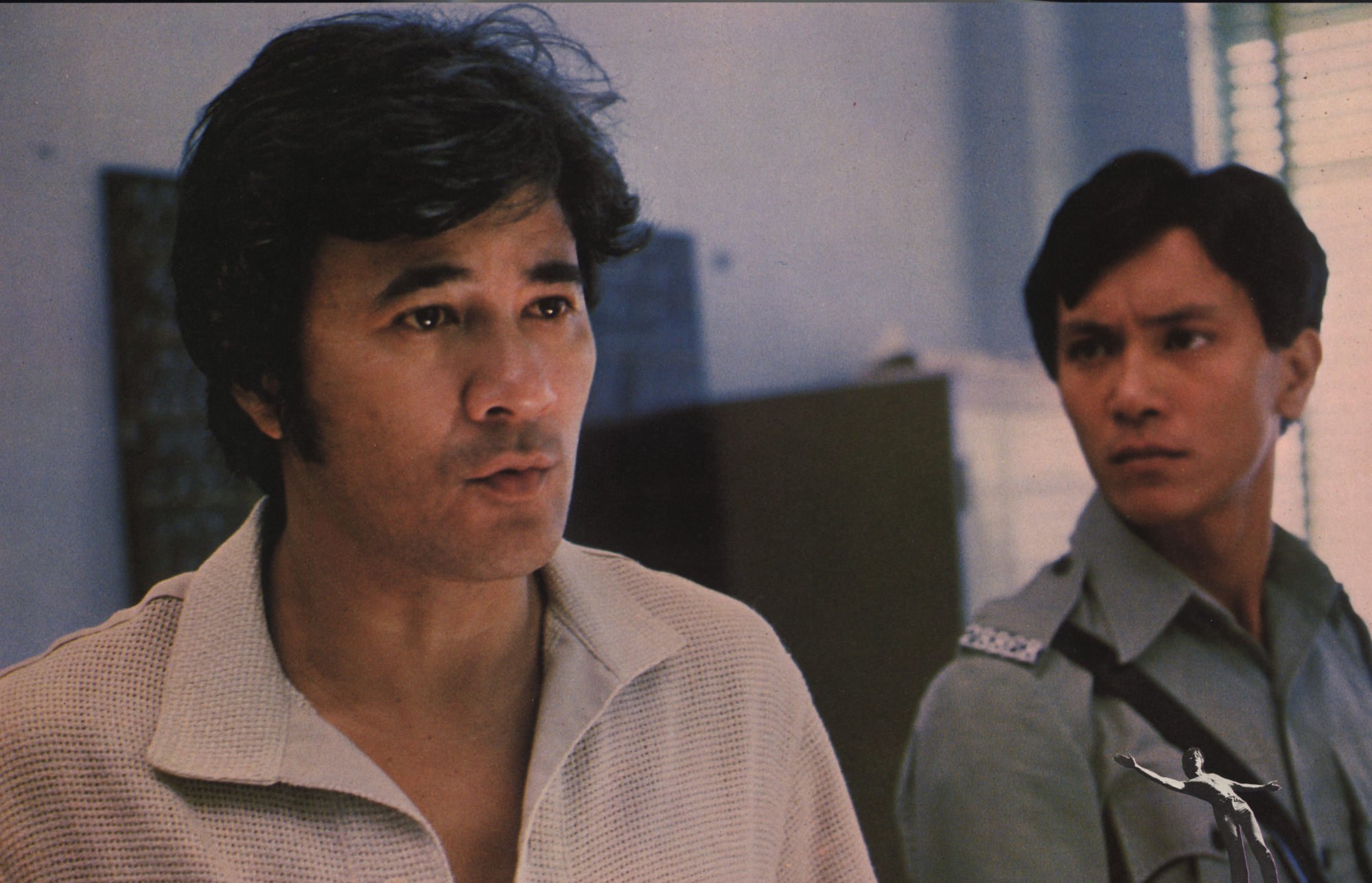

The crime thriller Jumping Ash – the term is slang for “drug peddling” – is generally referred to as the precursor to the New Wave.

The story revolves around a police officer who blows the lid off corruption at the top and suffers as a result.

“While the storyline is commercial in just about every respect, the storyline is based on real incidents and is highly credible,” Hong Kong film critic Mel Tobias wrote in 1976.

“The filmmakers have managed a professional look which clearly involved much technical know-how. For a Cantonese movie, Jumping Ash is very Westernised.”

Were there also action films in the New Wave?

The New Wave directors were generally not keen on action, as they were rebelling against martial arts films.

“Woo tended to be a loner, standing apart from the current trends in artistic development. The emergence of a New Wave in 1979 passed him by,” wrote critic Stephen Teo.

They liked making crime films, though

Crime was a popular topic for TV directors, and that carried over into their movie work. Crime was often used as a lens for social issues.

Who were the so-called Second Wave directors?

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.