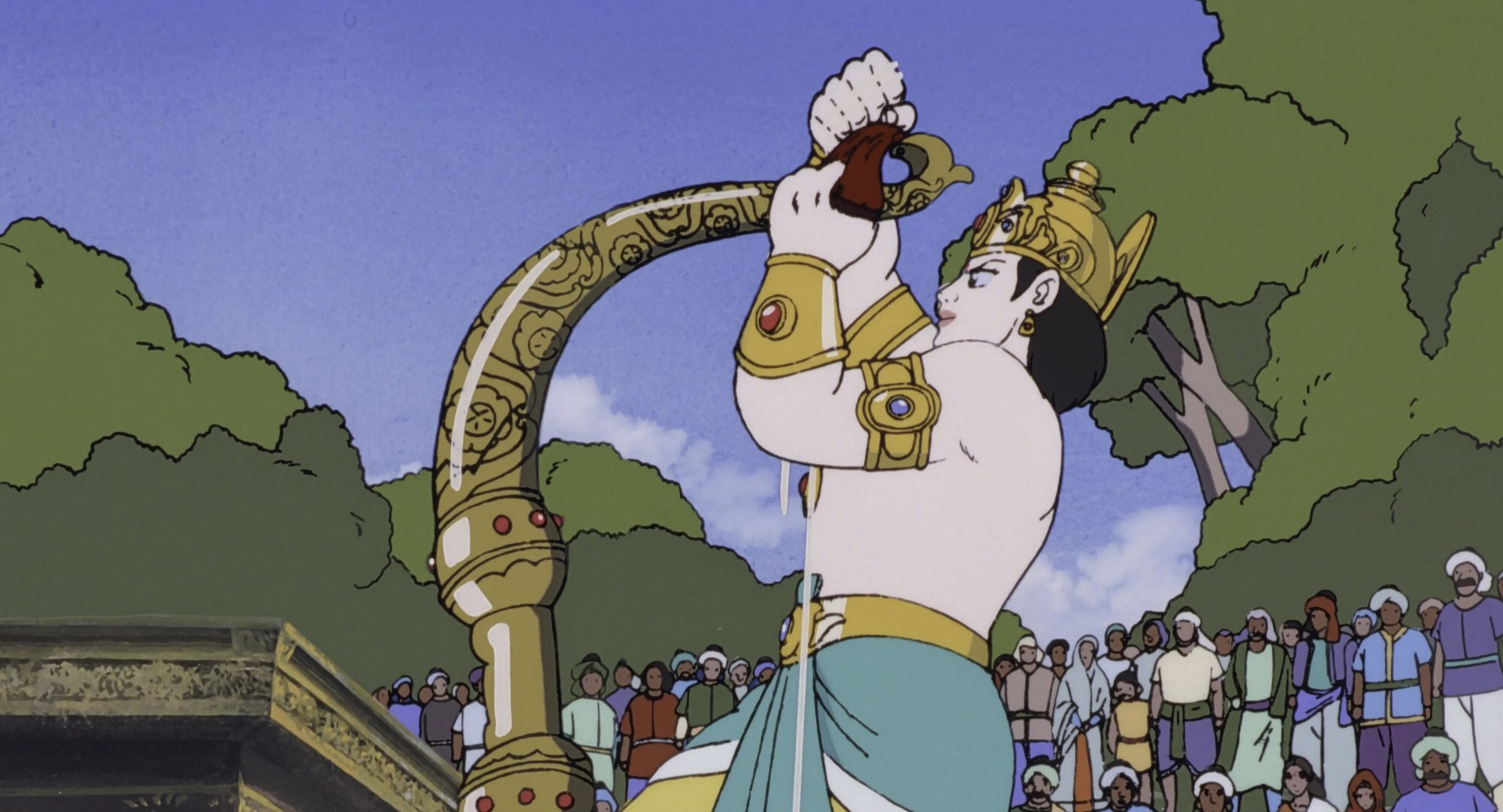

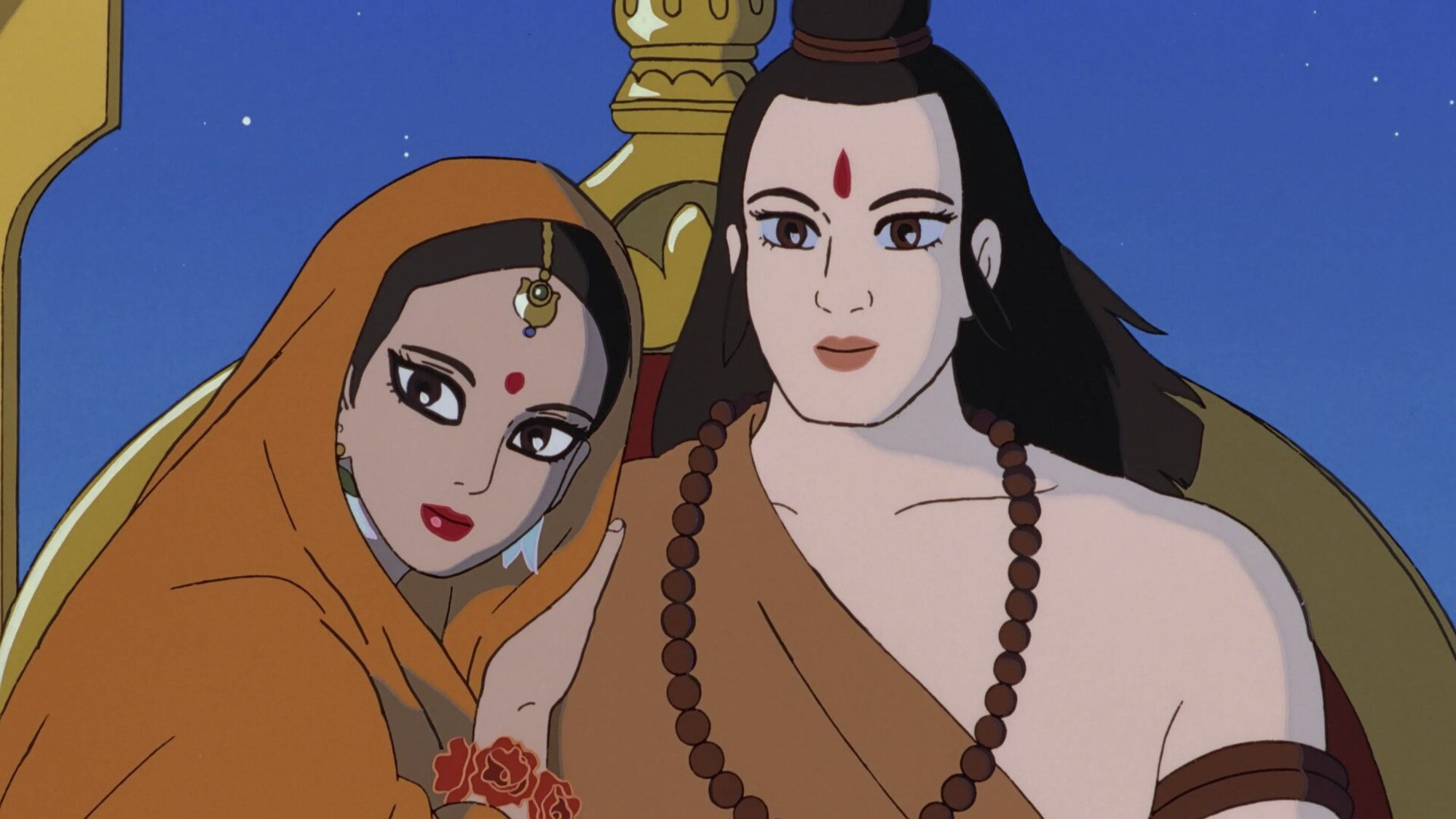

The ‘miracle’ of Japanese anime based on Hindu epic Ramayana, now digitally remastered to attract a new audience

- In an era before mobile phones, fax and email, Ram Mohan in India, the country’s ‘father of animation’, coordinated with filmmakers in Japan to make the anime

- They had to convince Indians anime could tell a serious story, but succeeded and it became a TV hit. Now a 4K digitally remastered version has been released

A Japanese anime based on the Hindu epic Ramayana released almost 30 years ago recently received a new lease of life in a 4K digitally remastered version.

Yoshii, along with Atsushi Matsuo, a director at TEM Co. (which owns the rights to the production) says Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama was made by a Japanese-Indian team at a time when international productions were uncommon in the Japanese animation industry.

“There were no mobile phones, fax or emails, and we were discussing images that we received via courier,” says Yoshii, adding that even telephone calls had to be kept brief because of the quality of the phone lines between the two countries in the 1980s.

Matsuo, who is also the executive producer, says it was “really a miracle” that the animation was completed under the circumstances.

The original anime was directed by Japan’s Koichi Sasaki and Yugo Sako together with Ram Mohan, known as India’s father of animation, and released in 1993. It cost 800 million yen, considerably more than the average for an animation film of that time.

Sako developed a passionate interest in the epic when he was working on a documentary about waterways in Asia, including the Ganges in India, and voraciously read all the Japanese translations of the Ramayana available at that time.

“He [Sako] was tremendously impressed with the story and also with the number of characters – humans, animals, even vegetables and plants – and said this was the ideal story for a film,” says the late Mohan’s wife, Sheila Rao.

Yoshii, also the assistant producer, says: “Sako said the most appropriate medium to convey a free-flow story like Ramayana across the world is through animation and not a movie.”

However, the project attracted opposition initially from a conservative religious group in India, as many in the country saw anime as just entertainment for children.

The Indian government even contacted Japan’s Foreign Ministry about the matter given that religious tensions in the multi-faith country were high due to a conflict about the Babri Masjid – a mosque constructed in the 16th century at a site believed by many Hindus to be the birthplace of Rama. The mosque was demolished by Hindu nationalists in 1992.

Animation … in India … was about simple cartoons … so if you said you were going to do Ramayana [via anime] they would immediately think ‘You’re crazy’

“It was as if Indians were making an animation on the Japanese imperial family, so it was natural for the Indian government to feel shock and worry,” reflecting the subject’s importance for Indians, Yoshii adds.

“Sako was not going to let it [the project] die and my husband kept on doing his work,” Rao says, relating how the Japanese director sought to explain to Indian doubters that anime is also made about serious topics in Japan.

“Animation was very nascent at the time in India,” says Ravi Swami, a British animator and illustrator. “It was about simple cartoons … so if you said you were going to do Ramayana [via anime] they would immediately think ‘You’re crazy’.”

But the work in fact did remarkably well on television as it was “quite groundbreaking in animation terms”, Swami adds. Many Indian children born in the 1990s waited anxiously for each episode at home, with little knowledge that Japanese animators had been involved, he said.

It also opened the door to a series of subsequent animations depicting Hindu gods and epics. “Watching Ramayana became a holiday ritual … and now you can’t find anyone who has not seen it,” says Mohan’s son Kartik, referring to Hindu festive holidays.

After TEM launched the remaster, some Japanese firms approached with suggestions such as making modifications to the storyline, but Matsuo again declined.

TEM now aims to set up a “Ramayana fund” from the earnings to contribute to “cultural exchange, world peace and human peace” at a time when the international community is going through such economic and political turmoil, Matsuo adds.