Hong Kong walled village memories: a Kowloon City exile snaps its fading history

John Chee, who grew up in a Kowloon City village, photographed some of its last stone houses in 2014 before most were demolished. He wishes more could be preserved to remind people of their roots

When John Chee was a young boy, he would go with his father to Checkerboard Hill in Kowloon City near their home. The hill is named after the giant red and white checkerboard which guided pilots to the old Kai Tai airport, and also features a stone pavilion with a chessboard table.

After his father died in 2014, Chee, now an investment banker and photographer living in New York, felt an urge to return, and wandered around taking photos of Hau Wong Temple New Village, the cluster of stone houses in Kowloon City where his father grew up.

He discovered that the stone pavilion was run down, its paint peeling – but still standing.

“It’s still very empty…almost like a hidden gem that no one cares about,” Chee says.

Last month, Chee published the book My Father’s Kowloon City, containing photos he took in his father’s village and in Nga Tsin Wai in 2014. An exhibition followed at the Stone House in Kowloon City, one of the Hau Wong Temple New Village buildings that has been turned into a heritage centre. The goal now, he says, is to document what’s left.

People really want to have some way to trace their roots – it means something

“It’s good that this stone house is being maintained now. I can take our next generation back and say, ‘Look, this is the place your grandfather lived in as a teenager.’ But the people from the walled village, they have no place to point to now. They cannot say, ‘This is where we come from.’ I basically saw a ghost village. It’s so empty.”

While the government’s Antiquities Advisory Board has declared some parts of these villages as historic buildings, Chee says many get ignored, even if they still matter to people.

“People really want to have some way to trace their roots – it means something.”

Chee says more than 1,000 people came to his exhibition, and he was struck by the memories they shared. One man recounted how he got dragged into the walled village and robbed as a youngster – the robbers took his wallet and the watch that his father had given him. Others talked about lying on rooftops and looking at the undersides of planes flying into Kai Tai airport.

Chee says some of the old buildings he photographed already had their windows boarded up, ready to be demolished.

Despite the doomed nature of the villages, Chee says he encountered optimistic residents during his photographic journey. For example, Chee recalls, there was Mr. Wong, an 80-plus-year-old owner of a general store who was about to close up because of pressure from his landlord.

Chee says he fears that indomitable spirit is not very common in the city any more.

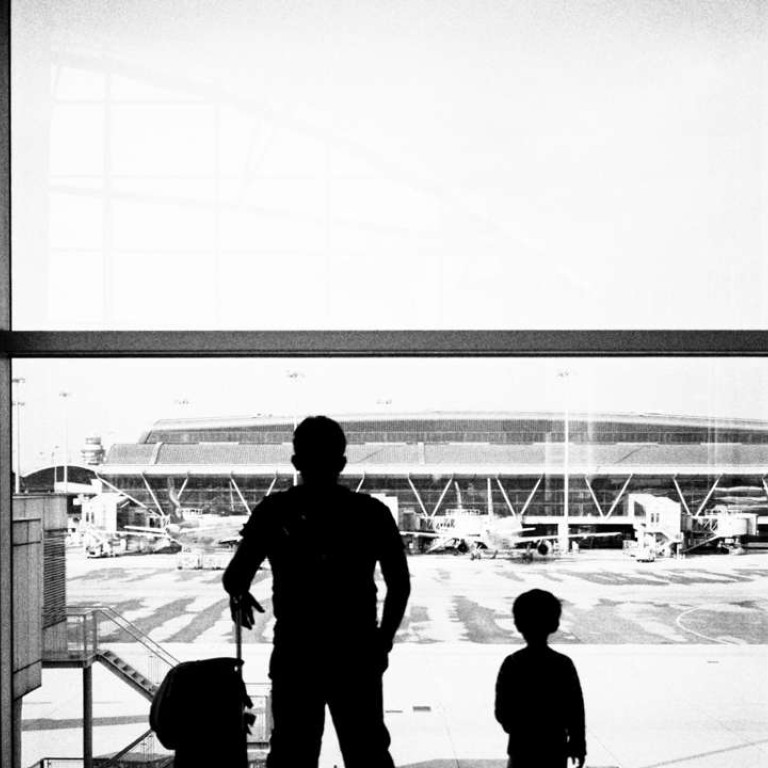

The book closes with a picture taken at Hong Kong International Airport of a father and son “looking out and imagining what the future’s going to be like”. He says the picture “represent leaving things behind, like how I felt when I left Hong Kong”.

Chee has no plans to return permanently, because he feels Hong Kong’s landscape, people and political atmosphere has changed. He cites the recent case of the missing booksellers as worrisome.

“Hong Kong doesn’t feel like home any more,” he says. “It’s not a place I want to come back to.”