How star Chinese architect behind Canada’s Absolute Towers thinks – Hong Kong exhibition goes behind the scenes of Ma Yansong’s MAD Architects projects

- Ma Yansong is arguably China’s most globally prominent architect, with his studio, MAD Architects, behind many eye-catching projects around the world

- An exhibition at the Hong Kong Design Institute Gallery is an overview of Ma’s near-entire career, offering insight into several of those projects

Beijing-based MAD Architects is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. For founder Ma Yansong, it’s an opportunity to look back and forward at the same time.

“Many projects are going to be completed next year, in 2025,” he says. “Many of them are also public buildings. That’s rare, for me at least, to have so many projects being completed at the same time.

“I felt I needed an exhibition as a platform to have a dialogue with the public, to let them know what is the thinking behind all these projects.”

That exhibition – “Ma Yansong: Landscapes in Motion”, on display at the Hong Kong Design Institute Gallery (HKDI) until April 7 – is an overview of Ma’s near-entire career.

He began his own practice just two years after finishing architectural studies at Yale University, with the intervening period involving stints working for pre-eminent architects Peter Eisenman and Zaha Hadid.

In two decades his studio has become known for buildings that appear to rise and fall like mountains, flow like water, and otherwise evoke the earth’s natural elements.

‘Full of adventures’: inside China’s award-winning school campus

With offices in Beijing, Los Angeles and Rome, Ma is arguably China’s most globally prominent architect, with work ranging in scale from individual pieces of furniture to enormous master plans.

The exhibition at HKDI, which was adapted from a larger show held at the Shenzhen Museum of Contemporary Art and Urban Planning in Shenzhen, southern China, in 2023, offers a behind-the-scenes look at several of those projects.

“We’ve showed many [objects] – models, sketches, the construction – to explain the ideas and thinking behind the process,” Ma says. “We start from the research of each location and explain this to the visitors. It’s like a narrative.”

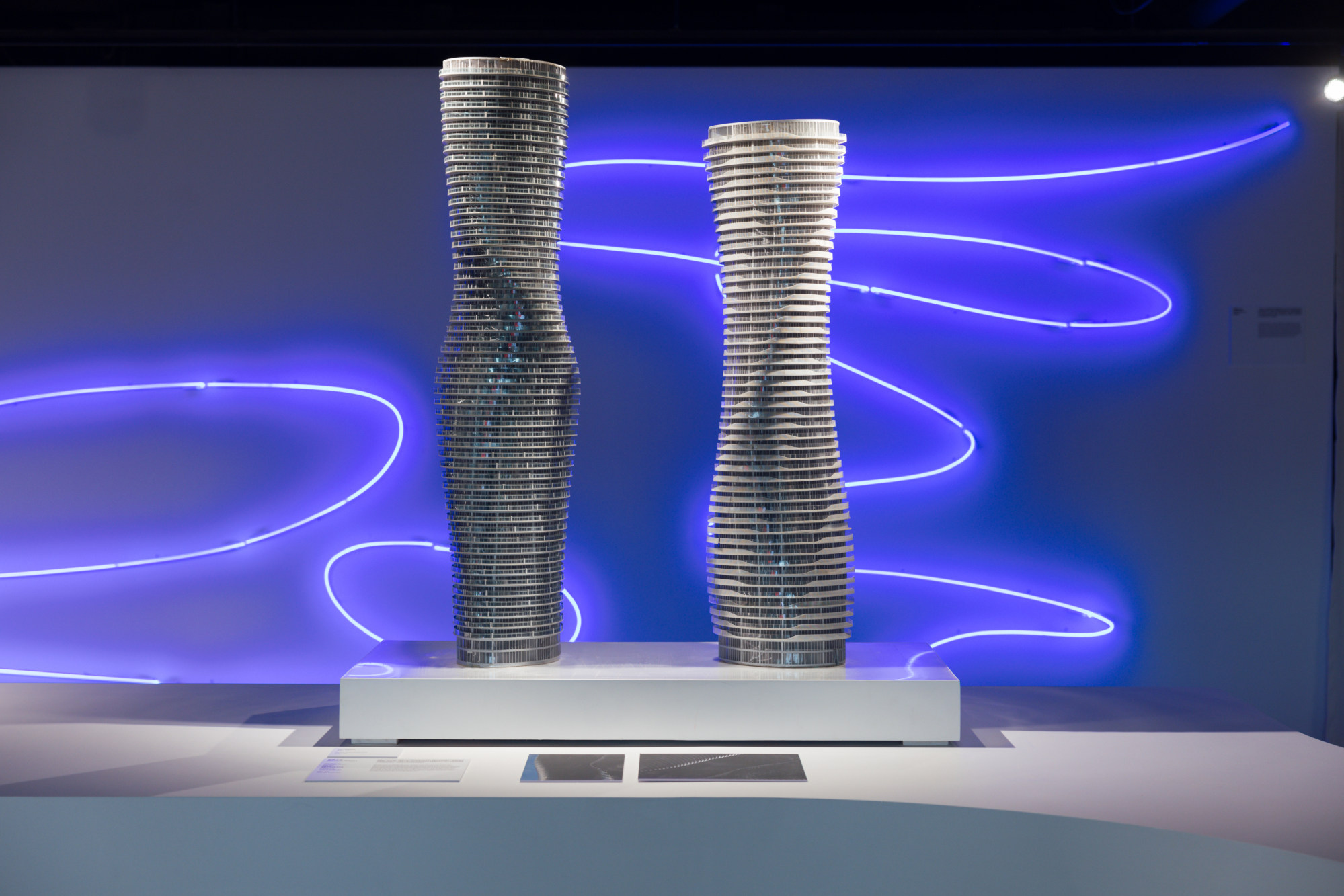

Some visitors will no doubt recognise the project that first earned MAD worldwide attention: the Absolute Towers in Mississauga, just outside Toronto in Canada.

Ma won an international competition to design the 50- and 56-storey apartment buildings in 2004. With curvaceous forms that twist 206 degrees from bottom to top, they were quickly nicknamed the “Marilyn Monroe” towers by local media.

Ma still sounds surprised to have been given such an opportunity so early in his career.

“That was a strange thing,” he says. “It was an open competition, I was a young designer and I started with this criticism of the city in general. I didn’t want to design a boxy, strong tower. I wanted to make it more natural. I didn’t expect it to get built.”

It went ahead as planned – and when the towers were completed in 2012, it minted Ma as one of the world’s newest “starchitects.” But even before the Absolute Towers were topped out, Ma was busy with a number of eye-catching projects in China.

The Ordos Museum, completed in 2011 in Inner Mongolia, northern China, is a bulbous metal structure that sits atop a desert landscape like a boulder. Fake Hills, the first phase of which was completed in the city of Beihai, in southwest China’s Guangxi region, in 2016, mimics a mountain range.

The Harbin Grand Theatre in Harbin, northeast China, completed in 2015, evokes the sinuous waterways of nearby wetlands.

These projects clearly take inspiration from natural forms, something Ma has continued to explore in his most recent projects. The Cloudscape, a public library in Haikou, on southern China’s Hainan island, which opened in 2022, uses concrete to create smooth, amorphous spaces.

“I want to dematerialise my spaces,” Ma says. “I use a lot of white, a lot of smooth surfaces to not attract people too much to the material. Of course I use glass because I need light, I need transparency. And concrete, yes, because I like the fluidity.

“But in most of the buildings, I don’t use too much texture or finishes. It’s more about the experience of the space, using light, the scale, the shape to make those experiences.”

He points to a few more recent buildings as examples of this approach. One River North, an apartment building in Denver in the United States completed at the end of 2023, is a glass box with a 10-storey “landscaped rift” that runs through it like a vertical canyon.

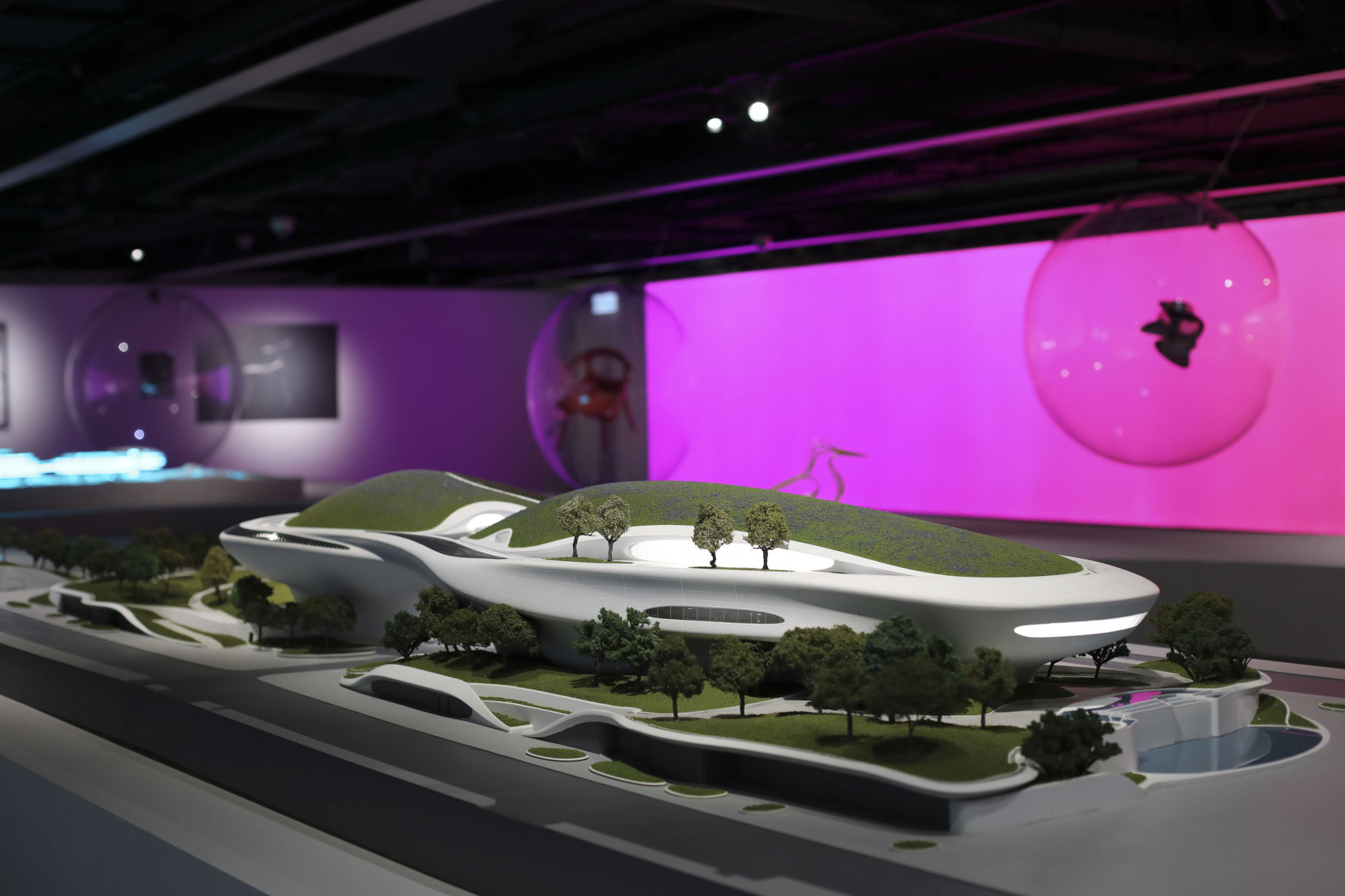

The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, currently under construction in Los Angeles, brings together the smooth concrete form of the Cloudscape with landscaped exteriors that attempt to turn the entire building into a public park.

Two more projects take this combination of natural and built forms to even greater lengths.

The Shenzhen Bay Culture Park in Shenzhen, currently under construction and slated to open in 2025, will include an assembly of structures that look like round river stones stacked upon one another, but most of the structure will be beneath a landscaped roof deck that attempts to merge into the surrounding landscape.

“Basically, I want to withdraw all the modern elements so the architecture and space is more abstract,” Ma says. “When people go in there they will feel a little lost and they have to enlarge their feelings of time and space to find a reference.”

How 3D printing is helping resurrect a century-old village in rural China

The 70-hectare Quzhou Sports Park in Zhejiang province, eastern China, does something similar by burrowing its structures under a landscape of what Ma calls “green volcanoes”.

The park’s centrepiece, a stadium with views of nearby mountains, was completed in 2022. The rest of the park, which is still under construction, will become the world’s largest earth-sheltered building when it is completed in 2025.

“It goes up and down so people can walk along the building shape,” Ma says. “They can arrive at the mountaintop, stay there and talk to the universe.”

At the same time, MAD is also working on projects that respond to the built environment, not just the natural environment.

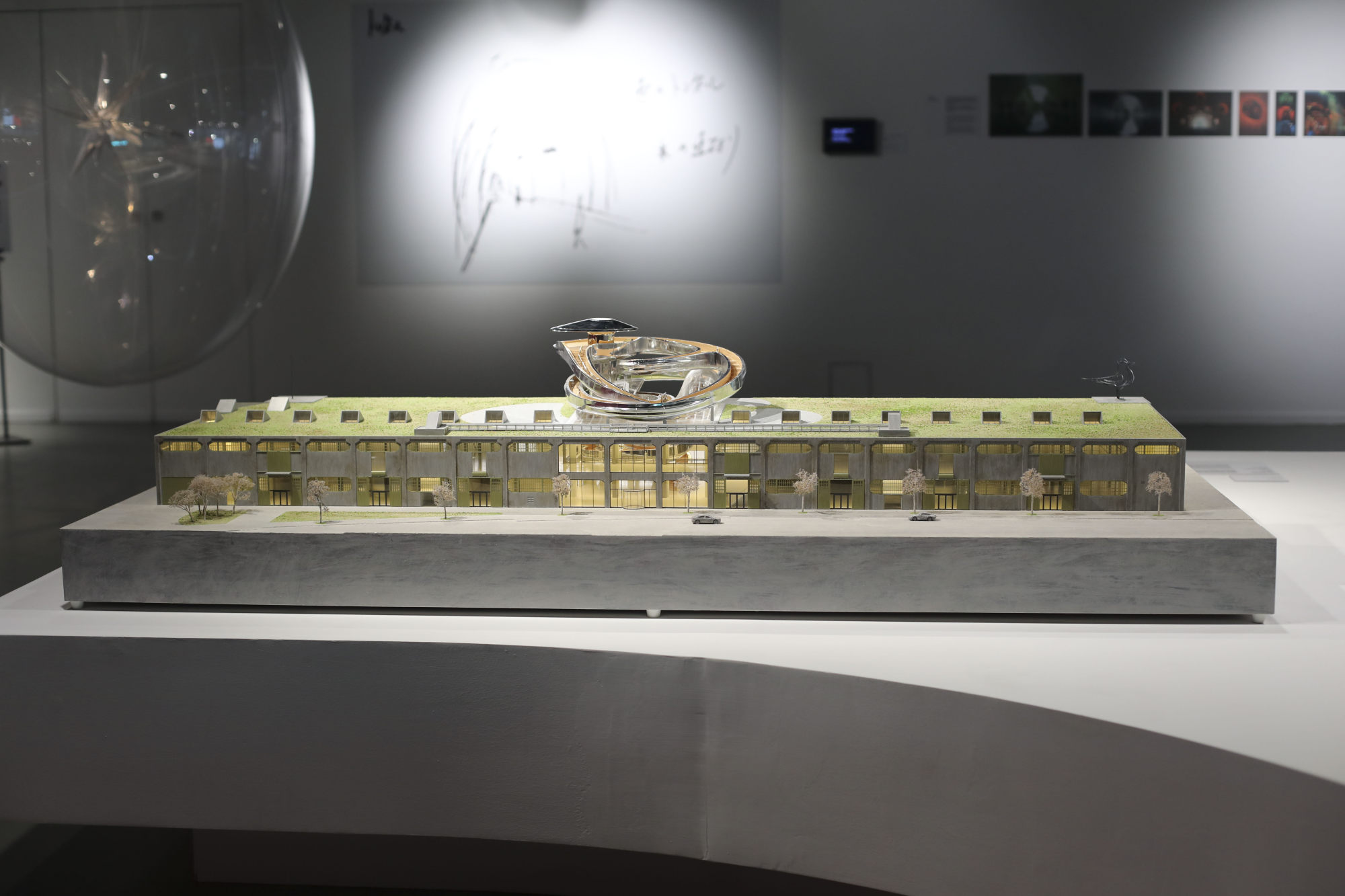

The Fenix Museum of Migration, slated to open in Rotterdam in the Netherlands in 2025, adds a gleaming, chrome-like spiral staircase structure onto a historic waterfront warehouse built in 1923.

The YueCheng Courtyard Kindergarten, completed in Beijing in 2023, encloses a traditional siheyuan courtyard house with a nebulous structure whose rooftop serves as an enormous playground.

“When I look back at the exhibition, [the projects] are so diverse,” Ma says. “It’s not a typical style of architecture. I think I’m still finding my way – I’m not fixed. It’s already 20 years of practice, but I think we’re still challenging things. We’re still young.”

Ma Yansong: Landscapes in Motion is at d-mart, Hong Kong Design Institute, in Tseung Kwan O, until April 7.