How American Chinatowns are fighting new redevelopment projects they say will harm their communities

- Chinatown communities in the US are uniting and rallying against projects including a new ‘mega jail’ in New York and a sports stadium in Philadelphia

- Activists say North American Chinatowns need to band together to promote and amplify each others’ issues to a wider audience

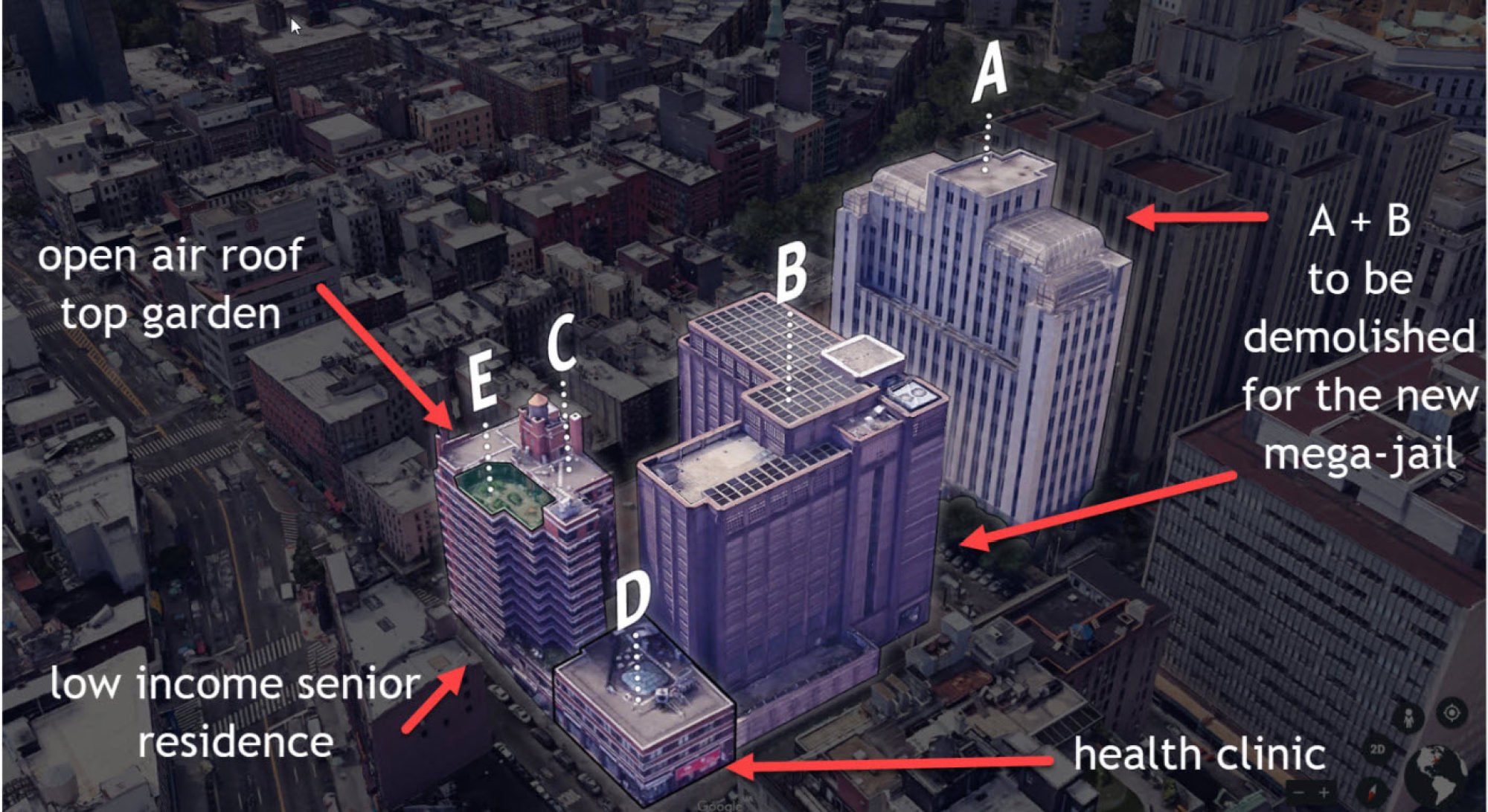

Demolition is under way at two jails, jointly known as “The Tombs”, that have been standing next to New York’s Chinatown since the early 1980s, to make way for a “mega jail” that will be about as tall as the Statue of Liberty and stretch over three blocks in each direction.

The authorities have said this new jail would be outfitted with state-of-the-art rehabilitation facilities to foster a more “humane” environment for detainees, and would also be less crowded.

Since 2019, Jan Lee and his fellow members of the Neighbours United Below Canal – Canal being Canal Street, the primary thoroughfare of Chinatown – have been trying to stop the estimated US$8.3 billion project, asking the municipal government to instead pursue the route of adaptive reuse, retrofitting the existing jails to meet current building codes instead of knocking them down.

“What we’re against is creating a jail that’s oversized, that is out of scale, and ultimately will be incredibly dangerous for the residents and the businesses of Chinatown,” Lee explains.

Oldest Chinatown in Australia faces suburban rival

“So what we’ve said is, you can adaptively reuse the two jails so that they remain jails, because jails have been there for a very long time, and nothing more.

“So we are OK with having jails. But we want them to reuse the buildings that are there so that the predictability of the size and scale is known to us.”

Lee was among the more than 50 advocates from 18 Chinatowns across North America who took part in the inaugural US-Canada Chinatown Solidarity Conference, held in Vancouver, in Canada, in May.

At the event hosted by the Vancouver Chinatown Foundation, attendees not only shared their experiences of the many challenges these communities face today, but also ideas on how to move forward. The two-day event also helped create a support network.

Disregard for residents and business owners in New York’s Chinatown, like many other Chinatowns in North America, has been occurring since the mid-19th century, when racism against Chinese migrants forced them to live in ghettos, typically near slum areas.

Thanks to Chinese people helping each other – whether it be finding jobs or setting up businesses – eventually these Chinatowns flourished and became vibrant economic and cultural communities in Canada and the United States.

However, in the last 20 to 30 years, these Chinatowns have declined due to various issues including gentrification, public security, fewer young people living in them and, more recently, anti-Asian hate crimes during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Many businesses – from restaurants to shops – have been forced to close down, while more homeless people and drug addicts can be seen in these areas.

There’s a potential for catastrophic failure of the buildings nearby

New York’s Chinatown is not alone in being threatened with massive redevelopment. Philadelphia’s Chinatown is now trying to stop plans to have an arena built for the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers next door.

Announced in 2022, the proposed basketball arena represents the biggest fight to date for Deborah Wei of Asian Americans United (AAU), a non-profit group founded in 1985.

She and others have so far managed to fend off the construction of a federal prison, casino and baseball stadium. But this fight against another encroachment on their community might be more difficult, with three multi-billionaire developers behind “76 Place”.

Artist’s watercolours contribute to Vancouver Chinatown’s revival

“Let’s just say they don’t have much of a conscience, because their bottom line is how much money [they] can make,” Wei says.

“They will buy properties, they’ll jack the rents up, they’ll evict people there. The idea is to increase the value of their property, [and] a lot of times that increase in value is artificial … and that makes their equity investment more valuable on Wall Street.”

According to the NBA website, the Philadelphia 76ers are a storied local institution with a proven track record of investing in their community.

“That’s why we’re committed to building a world-class home in the heart of the city and creating a privately funded arena that strengthens ties within the local community through investments that prioritise equity, inclusivity and accessibility,” said Josh Harris, a Philadelphia 76ers managing partner and one of the three main developers behind the project, to the press in July 2022.

“David Adelman [a Philadelphia business leader and another of the project’s main developers] shares our vision for ensuring that the new arena is an anchoring force in the local community, creating well-paying jobs and economic opportunities for those who need them most.”

AAU talked to numerous residents and business owners in Chinatown and united them in rejecting the proposal.

The municipal government said it would not give the developers the green light if those living and working in the area did not support the new arena.

However, after a recent raucous town hall in which Wei says everyone voiced their opposition to the project, the municipal government did not stop it – instead, the Chinese community was gaslighted, she says.

Why dating as an Asian-American woman can mean hyper-sexualisation and fetishisation

“No worries. It’s what has happened to Chinatown all along, historically. We’re used to being put in positions where, OK, you can live here but you can only live in a place we don’t want. And once we want it, we’re going to take it from you,” she says.

“What we’ve learned over time is that we not only have the right to fight back against that, we have the responsibility to fight back against that. And nothing surprises us in what politicians or developers will do.”

Wei and her fellow activists are continuing their fight by getting the people of the wider Philadelphia area to oppose the construction of the arena too.

“I think the people of Philadelphia recognise that Chinatown is valuable. They recognise that it’s like when scientists say you need biodiversity – cities need biodiversity, of race, ethnicity and class. And it’s one of the things that make cities special,” she says.

Meanwhile, in New York, third-generation Chinese-American Lee and other protesters have pointed out that The Tombs will sit on a former pond, and construction will cause water flows that will destabilise neighbouring buildings, including those in Chinatown.

“There’s a potential for catastrophic failure of the buildings nearby. And I should add, there is no evacuation plan for Chung Pak [a building housing senior citizens], which is on the jail campus – that’s 88 units of people … and the average age is late 80s and early 90s,” Lee says.

He adds there will be “environmental and sound pollution for years during construction”.

Lee is now following Wei’s strategy of aligning with the local black community. He led a small group of Chinese-Americans to take part in a rally organised by Harlem Mothers SAVE in February to end gun violence, as people in Chinatown are also concerned about public safety.

“They were surprised to see us but they were very welcoming. They gave us time to speak at the microphone,” he says.

“One in our group was the victim of pushing and shoving in the subway. And so she was able to speak, but the importance there is that when black people are crying out to be safe, we have to join them because we have that similarity in their neighbourhoods and our neighbourhoods, and they need to see that we will support them, and the same is true for the black community.”

The Vancouver conference has energised Lee and her fellow attendees, knowing they are facing similar issues and learning possible solutions. For Lee, the meetings help band North American Chinatowns together to promote each others’ issues to a wider audience and are a reminder to exercise their democratic rights.

“We have to be able to amplify each other’s issues. Even though we’re not experiencing a stadium [like Philadelphia], we should talk about that stadium in New York City. They should talk about the mega jail in Philadelphia, Washington, Chicago, Edmonton, Vancouver, when the issues are happening to one Chinatown,” he says.

Wei believes Chinatowns are not only places that hold history but are living, breathing communities that deserve to stay alive.

“We can’t forget the history of struggle that the Chinese went through, to be able to be in this country, to be able to say we are Chinese-Americans. When you erase these communities, you erase that history … of racism and discrimination and violence,” she says.

“But it is also a history of resilience, perseverance and strength. And the lesson in these communities in Chinatown is that we need to take care of each other. We cannot just be about hyper-individualism.

“I think the world has moved toward hyper-individualism, including China and Hong Kong. I think people in my organisation agree that that’s a wrong way to move in the 21st century. When you lose your sense of responsibility to others, you lose your humanity.

“So I think Chinatowns help us keep that sense of humanity and keep the history of why that’s important alive.”