Hong Kong at Venice Biennale 2023: sustainable, humane architecture to the fore as designers explore future of city at a crossroads

- The 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale spotlights processes shaping the built environment, and Hong Kong’s contributions highlight the city’s transformation

- The development of rural areas and the chance it gives to reshape the city are explored, as is the community-centric use of space in its public housing estates

When Scottish-Ghanaian architect Lesley Lokko took the helm of the 18th Venice Biennale of Architecture, the penny dropped. “An architecture exhibition is both a moment and a process,” she wrote in her introductory note to the biennale.

The same can be said about the built environment. It can be captured, recorded and studied at any given moment, but its evolution is constant: understanding it requires understanding the processes that shape it.

“Laboratory of the Future” is Lokko’s theme for this edition of the biennale, which ends on November 26, and the hundreds of exhibitors taking part are looking into each cog of the vast machine that is propelling society into uncertain times ahead.

“We wanted our exhibitors to focus on the design process and not only the outcome,” says architect Yutaka Yano.

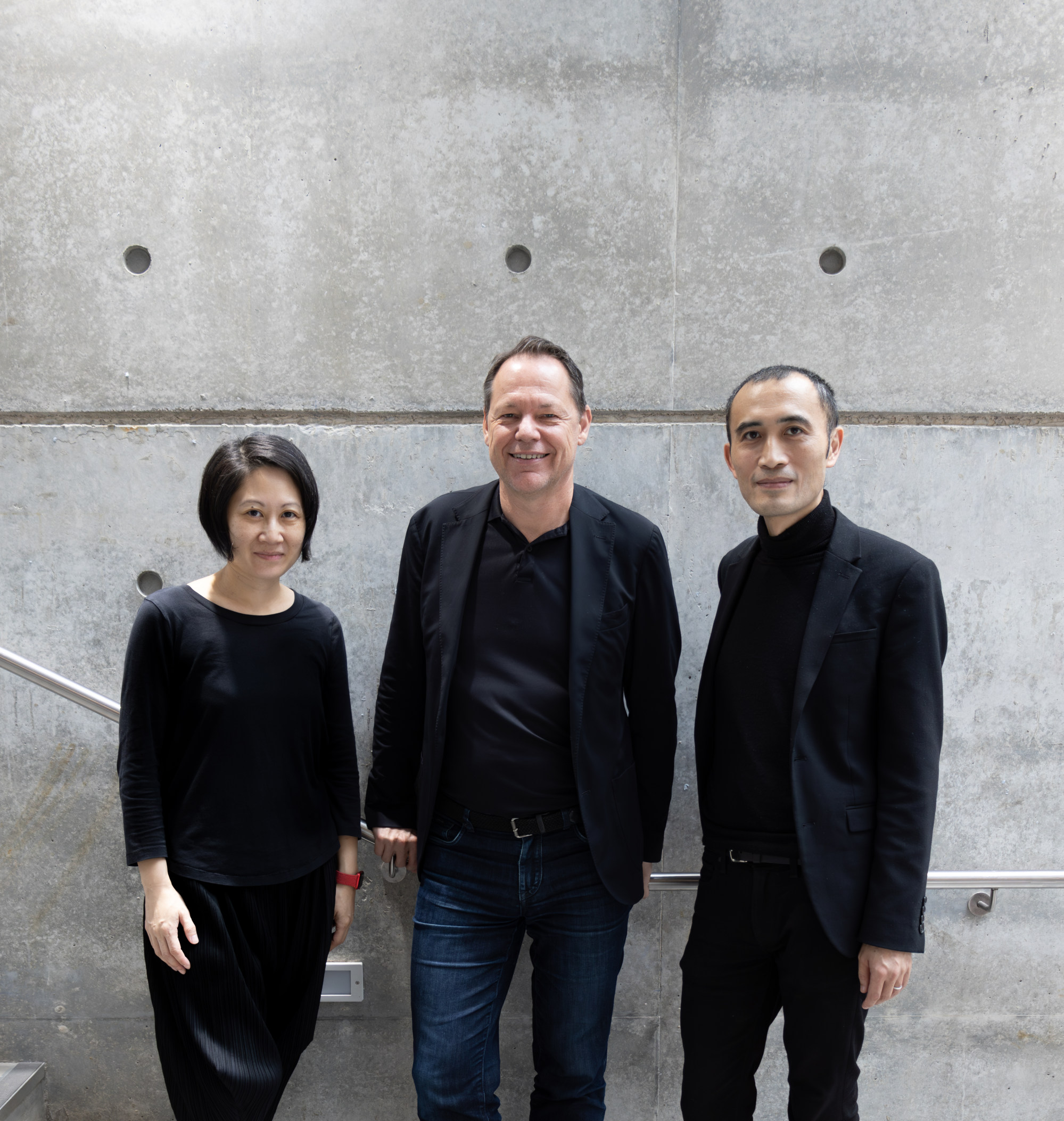

Yano and co-curators Hendrik Tieben, head of the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s (CUHK) School of Architecture, and Sarah Lee, Yano’s partner in architecture firm Sky Yutaka, argue that Hong Kong is at a pivotal point that will define it for years to come.

At the same time, there are countless hurdles to overcome, including the impact of climate change, the challenge of an ageing population, and growing demands for more humane, accessible and sustainable urban spaces.

“There’s a huge spectrum of scales in the exhibition, and that was a really important aspect of it for us,” says Tieben.

How Hong Kong uses green buildings to help fight climate change

He and Chan, a research assistant at CUHK, say the canopies could serve as prototypes for outdoor event spaces or temporary buildings, while also keeping a quintessential Hong Kong craft alive for new generations to learn.

How green building design can help take heat off Hong Kong

In a room with terrazzo floors and ancient ceiling beams, several other exhibits are displayed on mobile wood stations designed by Sky Yutaka that are inspired by shipping crates.

One display outlines the MTR’s plans for a 10.7km (6.6-mile) railway that will run through the far northern New Territories to serve the new town development, under way for the Northern Metropolis, near the border with Shenzhen in mainland China.

Several exhibits explore the implications of new technologies on scales large and small.

Global engineering firm Arup has a display explaining how Modular Integrated Construction – which plugs together components that have been pre-made off-site – can be used to reduce construction waste and lower building costs when creating new housing and other types of structures.

Made of biodegradable flax fibre, the stools are strong, lightweight and stackable.

“Hong Kong public housing has been successful at creating spaces where people can gather and form communities,” Cheng says. He credits this with 50 years of evolution, something the exhibit documents through illustrations, maps and photos.

He notes that the earliest estates, such as Wah Fu Estate, in Hong Kong’s Southern district, dealt with hilly topography by creating superstructures connected by footbridges, essentially creating an artificial ground level perched atop the natural one.

By the 1980s, new estates had become “more sensitive to the landscape”, with a more fine-grained approach to public spaces.

While Cheng focused on analysing the design of each estate, Provoost captured how these spaces are now occupied.

This reveals what Cheng calls the “generosity” of many estates, which place community needs ahead of profit by offering more space to linger than private estates or older neighbourhoods.

That raises the question of public participation in design and architecture, something that has become increasingly relevant in the past decade.

Multifunctional design magic, from furniture to interactive ceramics

Several projects showcased were based on a participatory design process, such as Lead8’s workshop with schoolchildren, the co-creative design of the bamboo canopies and HIR Studio’s approach to working, which is based on user studies and public input.

“There is definitely more participatory design in the works we see now [than in the past],” says Yano.

Tieben ascribes that to the “diversity of actors that make the city”, adding: “A lot of people, whatever their politics, try to contribute to the city and make it work.”

The life that has been erased

Capturing the spirit of the moment and Lesley Lokko’s curatorial approach, the focus of the 18th biennale is on decolonisation and decarbonisation. In many cases, attention centres on issues around architecture, rather than architecture itself.

A case in point is architect and photographer Justin Hui’s Unsettled Ground, an installation that pairs photographs of Chinese investment in Africa with the redevelopment and changes under way in Hong Kong’s northern New Territories.

In 2014, Hui visited Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia to assess the impact of massive Chinese investment in those countries.

He visited skyscrapers built by African and Chinese workers who communicated entirely though hand signals, as well as special economic zones run by China on 99-year leases – a model borrowed from the British, who acquired the New Territories in 1898 on similar terms.

Photos of the New Territories depict an area on the cusp of complete transformation, as the Northern Metropolis scheme replaces farmland and rural villages with a new town that will bolster Hong Kong’s connection to Shenzhen.

Paper stools, blood powder planters: the future of sustainable homewares

One of Hui’s images documents a pile of stone lions retrieved from a demolished village, new towers rising in the background. Many depict everyday objects that Hui found in abandoned villages.

The New Territories has traditionally been seen as the outskirts of Hong Kong, but Hui notes it is the part of the city that has been settled the longest.

‘It just didn’t feel penthouse-y’: Hong Kong flat has luxe Italian upgrade

“It’s actually the oldest part of the city. You encounter a lot of artefacts and mythologies that are not part of the colonial narrative.” With Hong Kong ever more integrated with the mainland, he asks, “should we re-fix our gaze back to the north?”

At the same time, Hui wants viewers to question why the northern New Territories is being developed. “I’m not opposed to development, but if it’s just repeating what’s already been done in Hong Kong, we’re squandering a massive opportunity to rethink what Hong Kong should be in the next 50 years.”