‘Art was his lifeline’: how schizophrenic Hong Kong artist Wesley Tongson used creativity to deal with his condition, and how art therapy can help you

- Wesley Tongson discovered art at 17 and found the creative process soothing – his artworks have since featured in solo shows around the world

- Art is important for mental health and helps people connect with their emotions in a way that’s deeper than simply through language, one expert says

When the late Hong Kong artist Wesley Tongson was 15, he persuaded his parents to send him to Vancouver Island, off Canada’s Pacific Coast, to attend boarding school.

About three months later, he disappeared into some nearby woods overnight because he thought that someone was after him.

His parents flew to Canada and brought him home, where he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. It was 1973, and his family didn’t know what to do apart from following doctors’ instructions and giving him prescribed medication with serious side effects.

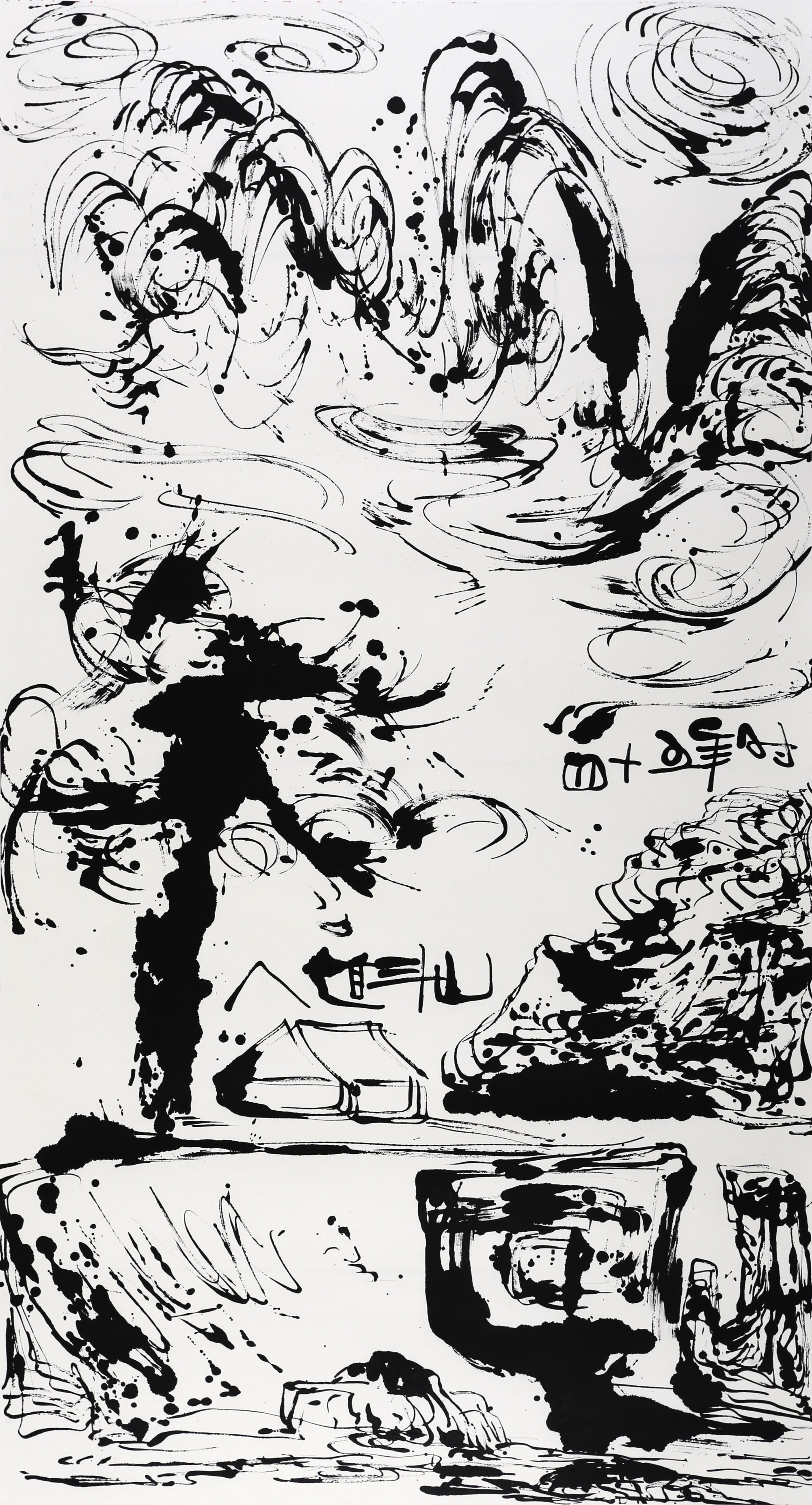

And then he discovered art. At 17, Tongson started practising Chinese ink painting and went on to become a prolific painter known for luminescent abstract works and dramatic landscapes painted using his fingers and nails.

Also known by his Cantonese name Tong Ka-wai, Tongson spent years working in obscurity and died at home in 2012 of unknown causes.

Now his paintings have caught the attention of the art world. Earlier this year, Galerie Du Monde showed his work in Art Basel Hong Kong’s Kabinett sector, and he has been the subject of major solo exhibitions, including a 2022 show at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in the US.

“Stylistically, and technique wise, he stands apart,” says curator, art historian and art adviser Catherine Maudsley, who has been instrumental in bringing Tongson’s works to a wider audience since 2014. “And then to know that he also had these personal challenges and overcame them through his art is doubly inspiring.”

Art was his lifeline, says his sister Cynthia Tongson.

“In the 1970s, there were no support groups or resources. You hardly had any counsellors so everybody had to suffer alone and find their own way.”

After secondary school, Wesley Tongson moved to Toronto, where he attended Ontario College of Art and Design. Four years later, he returned to Hong Kong. He started painting through the night and sleeping all day. Only in his 40s did he speak to a psychologist. He suffered from paranoia and had few friends, his sister says.

Despite – or perhaps because of – his illness, he experimented tirelessly. In the early 1980s, he became fascinated with possibilities beyond traditional brushwork and adopted spontaneous techniques involving splashing and flinging water and ink. He also explored ink rubbing and marbling techniques, which added a sense of movement and depth to his landscape paintings.

He was exhibiting works locally at the time but then he withdrew from view. “He became a hidden and forgotten artist after 1995,” his sister says. “He had trouble being out in public. He couldn’t be out there in a crowded gallery reception. He felt afraid.”

Many of his works reflected his inner journey, she adds. In Untitled, (Mountains of Heaven series, #242) for instance, she suggests the light emerging from behind two dark, imposing mountains is a symbol of hope.

Toward the latter part of his career, he began applying ink with his hands, fingers and fingernails. “He always wanted to have a better connection with his painting. So by removing the brush, he could directly pour his emotion into his art and express himself better,” his sister says.

After his death in 2012, his sister discovered diary-like notes scattered around his flat, including some explaining the healing and liberating effect of art.

In one note he wrote, in Chinese, “To tackle my bad or unstable mood swings at night, I have to make clear to myself that I will feel good when I see the sunlight after a good night’s rest. I should always remind myself that I have my paintings and calligraphy to keep me company, my adept brushwork through years of intense practice, and then my mood will be good.”

Odile Thiang, lead clinical adviser (training and antistigma) at mental health charity Mind HK, says art is very important for mental health and helps people connect with their emotions in a way that’s a lot deeper than just through language.

Thiang believes that in Hong Kong, where little effort is put into preventing mental illness, art therapy – creating art to express and resolve emotions in the presence of a registered therapist – can be an important preventive measure.

In the 1990s, no one had heard of art therapy and they were sceptical, says Julia Byrne, art therapist at Lifespan Counselling and founding president of The Hong Kong Association of Art Therapists. But now people are more open to it.

“Making art reduces the stress hormone cortisol, while increasing serotonin levels in the brain, which contribute to a better mood,” she says.

Earlier this year, Hong Kong’s M+ museum of visual culture offered art therapy sessions to visitors as part of its recent exhibition featuring Yayoi Kusama, a famed Japanese artist who lives in a psychiatric institution.

“When I did another Kusama exhibition six years ago, it was common practice not to talk about mental health, but now people are more comfortable,” says Keri Ryan, lead curator, learning and interpretation, at M+.

The art therapy workshops, which were co-organised by The Centre on Behavioural Health at the University of Hong Kong, were so popular that several participants returned, says Ryan. “The opportunity to be creative in a safe environment was very important for them.”

“Wesley didn’t have many people to talk to or these kinds of resources,” reflects Cynthia Tongson. “We need more education so people are aware that mental illness is nothing to be ashamed about.”

Resources in Hong Kong

-

Lifespan Counselling