Thai film director Apichatpong Weerasethakul on his Hong Kong art show, how making movies is a ‘silly attachment’, and why ‘nature is the ultimate art’

- In ‘A Planet of Silence’, Apichatpong Weerasethakul uses images of the Mekong River and South America to show the world in a new way, he says

- The Palme d’Or winner says his work isn’t political, but rather philosophical musings, free from a sense of time and space, that promote the idea of connection

Palme d’Or-winning Thai film director Apichatpong Weerasethakul is known for his haunting films which blur the boundaries between the physical and spiritual, the living and the dead, the mythical and the real.

For an exhibition in Hong Kong of his art, “A Planet of Silence”, Apichatpong has conjured a similar dreamlike atmosphere at the new Kiang Malingue gallery in the Wan Chai neighbourhood.

Taken together, the images, shot in Peru, Colombia and northeast Thailand, explore new ways of looking at the world, the filmmaker says. “The distance between different places doesn’t matter. There is this idea of connection and an awareness of oneness.”

Mekong, a Quiet Phantom (2021), which is hung upside down to make it all the more surreal, shows a view of the beleaguered river through two window frames in an abandoned hotel where he once stayed.

During that road trip, Apichatpong saw student protesters from his old university in Isaan rebelling against the government, military and monarchy. “For my generation, it was impossible to question authority,” says the filmmaker, who was raised in the city of Khon Kaen by parents who were both doctors.

Since 2019, however, there has been a big protest movement in Thailand, which he never imagined would happen. “For my generation the monarchy was untouchable.”

Apichatpong first studied architecture in Isaan but later pursued his filmmaking dreams at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, in the United States.

He shot to fame when his feature film Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 2010.

Over time, he developed a parallel career in the art world exhibiting in biennales and museums worldwide, but he remains best known for his slow, immersive films, which often have a political undercurrent.

Several works in the Hong Kong show tap into Thailand’s charged political landscape, such as Of Love, Of Lights.

On a photograph of an dilapidated cinema in Isaan, he has superimposed an image of a screen showing a mass antimonarchy demonstration in Bangkok in which the crowds are clutching mobile phones with flashlights turned on to evoke a sea of stars.

Apichatpong resists the label of political artist, however. “I’m most curious about people’s way of living, our relationships with each other, with fear and love,” he says. “The way I make art is actually self-exploration; there’s no trace of activism.”

The Hong Kong exhibition oscillates between striking images from the Mekong and from South America, where he shot Memoria. The film was the first he had made outside Thailand, and doing so made him realise people’s struggles and emotions are universal.

“It is the same – it’s all human,” he says. “So for me, the Mekong River and … the jungles of Colombia are one place.”

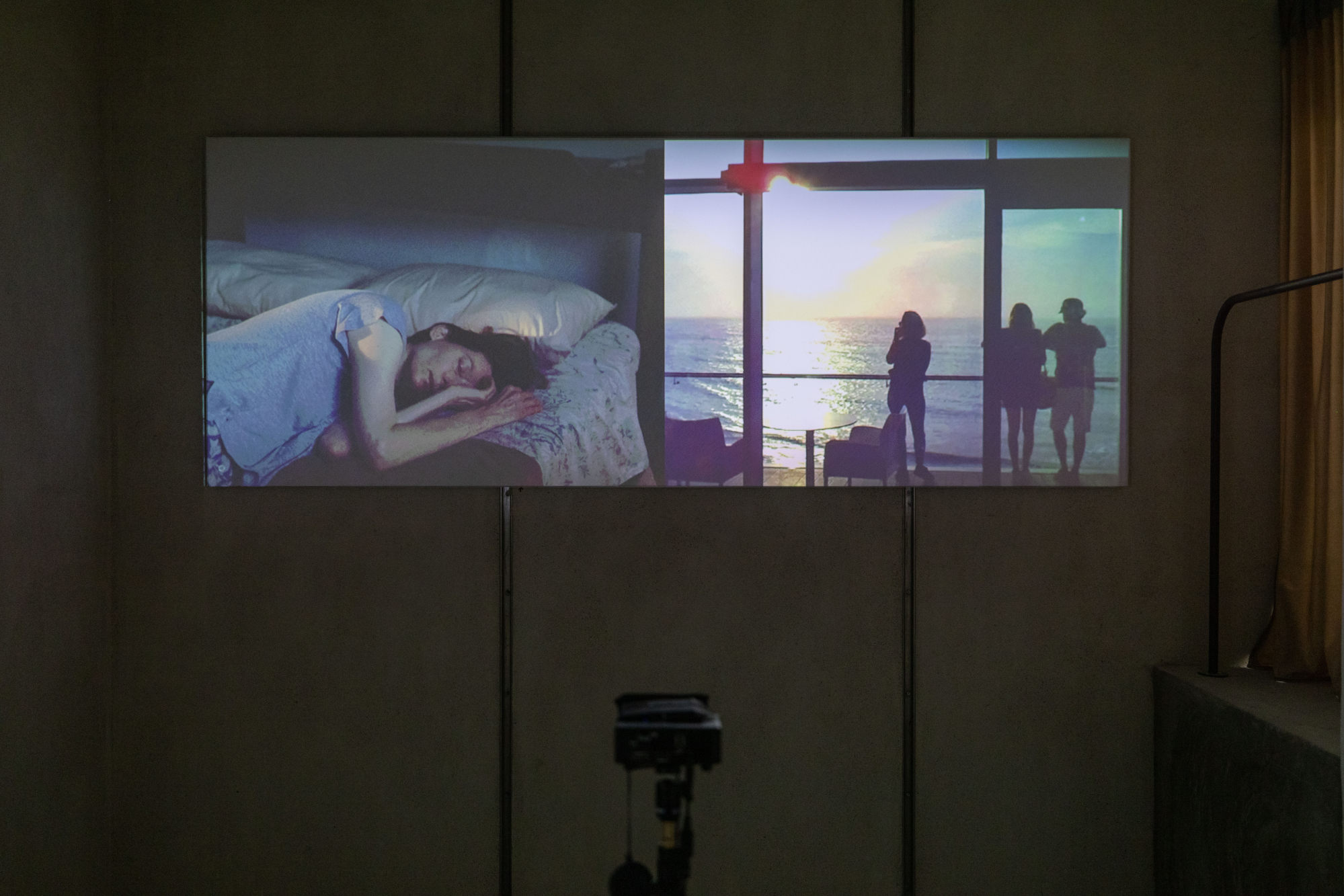

Walking up some stairs, the hum of insect life fills the air. The sound comes from a first-floor viewing room showing a dual-channel video installation called For Bruce (2022), which Apichatpong created in Peru.

While recovering from a Covid-19 infection and walking in the Amazon jungle, he came across a bridge where he stopped to reflect on his filmmaking journey and the influence of experimental filmmaker, and an old friend, Bruce Baillie.

Set in a nondescript location with no narrative, the work is free from a sense of time or place – a notion inspired by the writings of Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti.

Reading Krishnamurti’s work has been humbling and transformative, Apichatpong says. The philosopher promotes the idea of a mind that isn’t self-centred and a consciousness that is free from the burdens of time or memory.

“He forced me to ask the question: ‘Why do you make films? I realised it’s really just a silly attachment … I don’t put [filmmaking] on such a high pedestal any more. It’s just a part of living.”

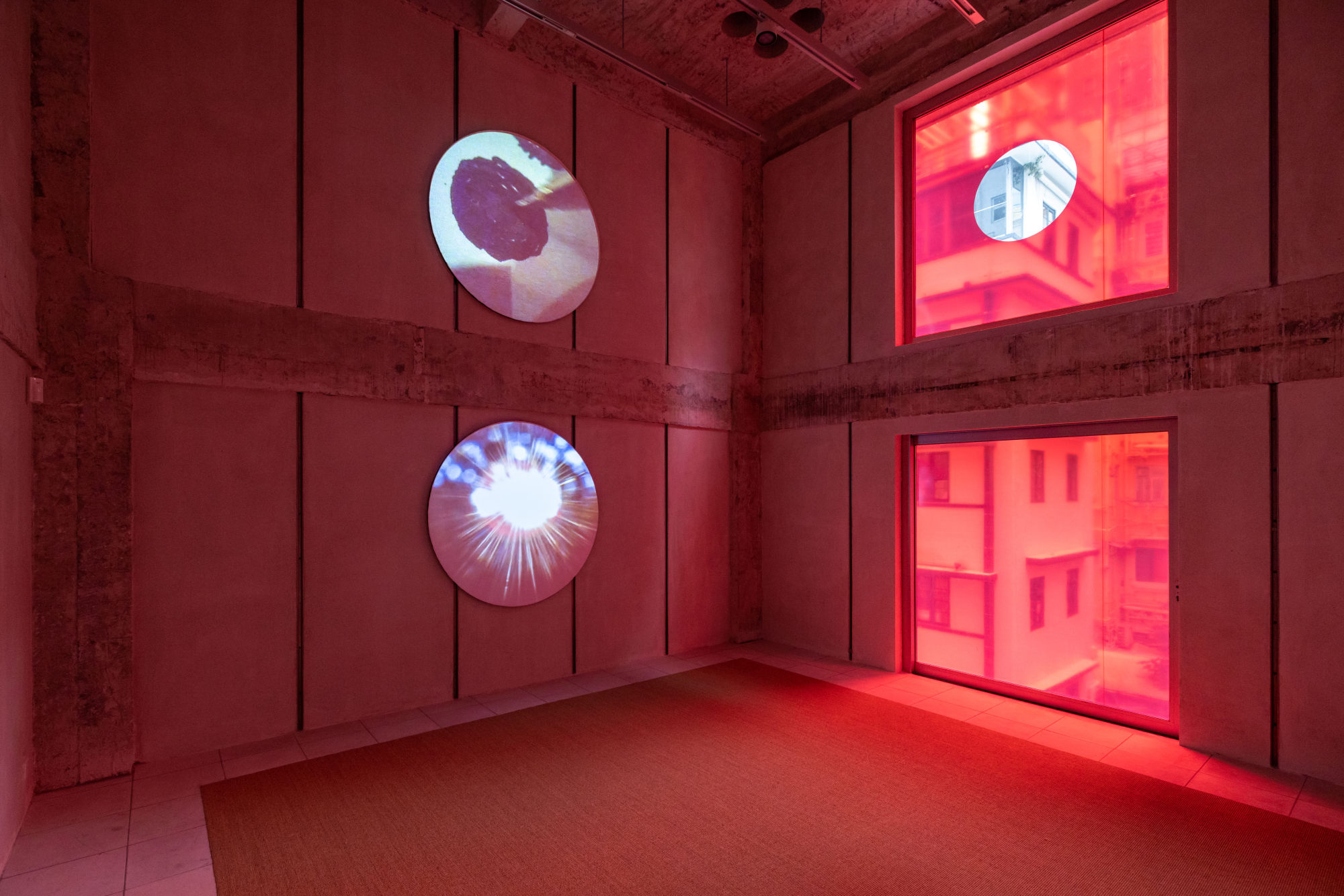

As if to reinforce that point, the top floor of the gallery features two videos of flickering, seemingly random images shot with a pocket camera that are projected onto large circular screens.

The windows in that room have been covered in red film with a circle cut out, creating a meditative environment that invites the gaze to the skies outside.

“For me, nature is the ultimate art,” he says. “Because it’s not fixed. When you look at the trees or a mountain, you realise these things are in the process of transformation. Good artwork should reflect this.”

“A Planet of Silence: Selected Works from 2021-2022”, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Kiang Malingue Sik On Street, 10 Sik On Street, Wan Chai, Tue-Sat, 12-6pm. Until January 28, 2023.

“A Bunch of Shorts Portrayed in Red” – a marathon screening of Apichatpong's short films – takes place at the gallery’s Aberdeen, Hong Kong location until January 7, 2023.