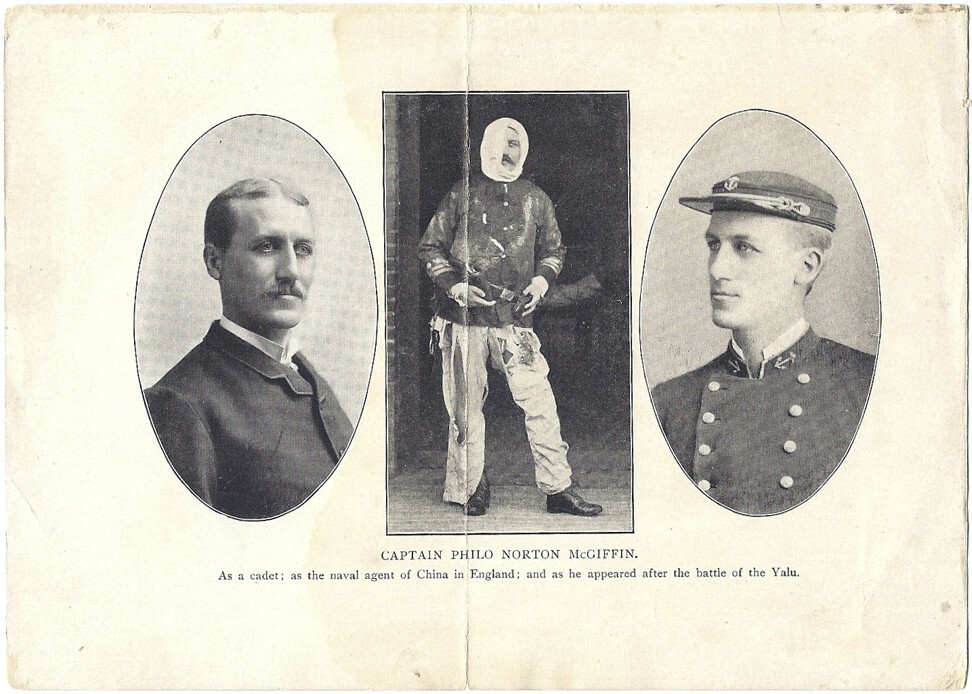

‘Treachery’: how US officer who fought for China in first Sino-Japanese War came to a bad end

- Unable to obtain a commission in the US Navy, naval officer Philo Norton McGiffin left America in 1885 to seek employment in China

- His story, including being seriously injured during a battle against Japanese warships, is told in a Hong Kong Maritime Museum online exhibition

The modernisation of China’s military is widely perceived as a threat in the United States today. Yet some 135 years ago, one US naval officer travelled to the Middle Kingdom and was engaged to help the country develop its prowess at sea – and it did not end well.

After eight years of intensive officer training, McGiffin failed to obtain a commission in the US Navy because of the lack of available ships in its tiny fleet. So instead he travelled to China, to seek employment fighting for the country in the Sino-French War (1884-85).

“McGiffin is an important figure in the naval development of the early modernisation of China and his story is really interesting,” says Katherine Chu Man-yin, consultant curator (archives, library and special collections), who curated the online exhibition that launched this month.

The war with France was over by the time he arrived in the country, but McGiffin, almost out of funds, managed to secure temporary command of an ironclad battleship in dry dock, before taking up the role of an instructor at the naval academy in the northeastern city of Tianjin.

“The McGiffin story is a good example of how China wanted to modernise with the help of the West after being defeated in various wars,” Chu says.

The Danes who defied their king to enlist in Hong Kong’s defence

His 12-year adventure in China also resulted in him being the only American naval officer to serve in action aboard a Chinese battleship.

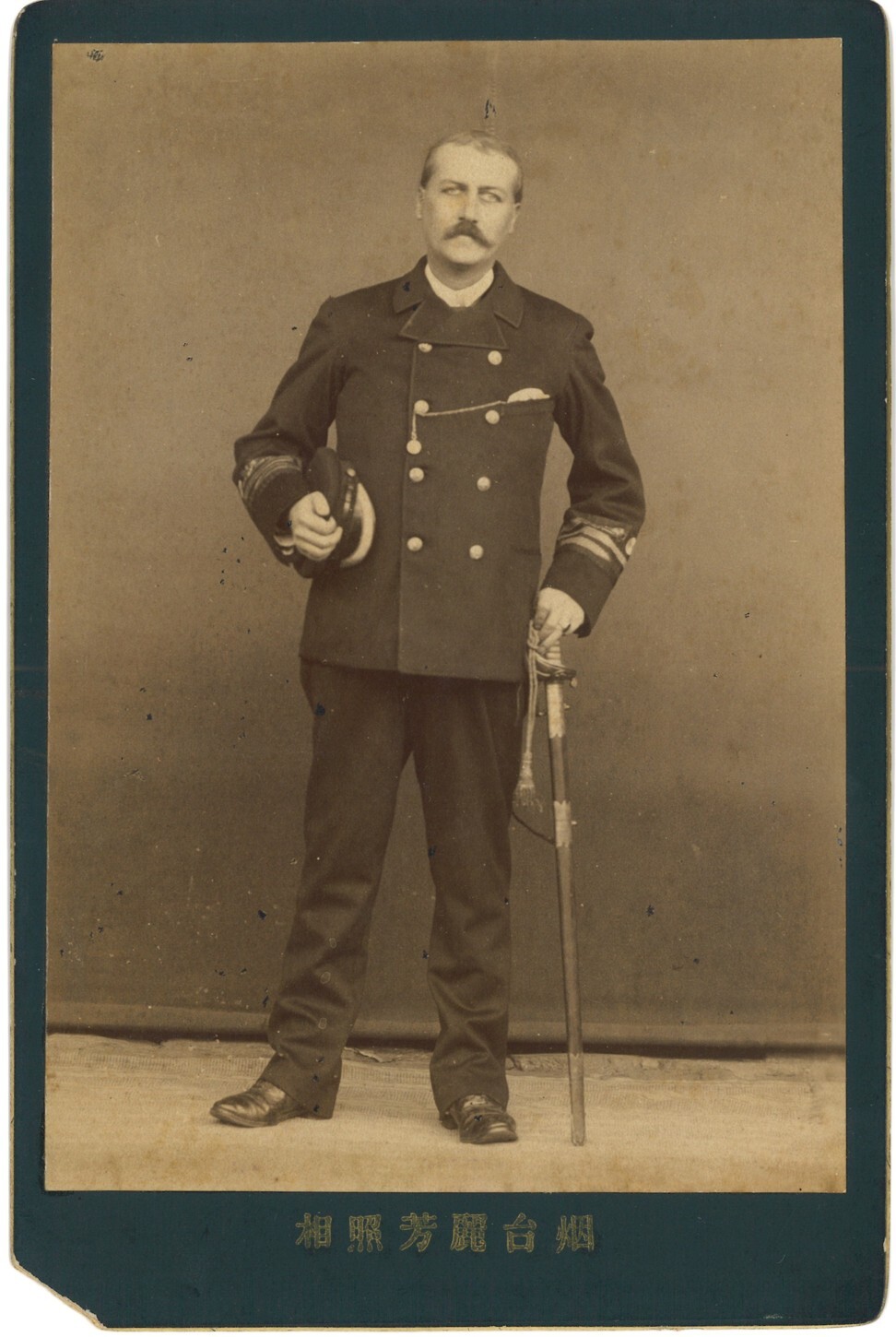

His unique experience is recorded in a collection of some 150 artefacts and archives that the museum acquired from an auction in San Francisco in the US some years ago. Personal items such as his Imperial Chinese naval officer’s dress sword and dress jacket are on display in the museum galleries.

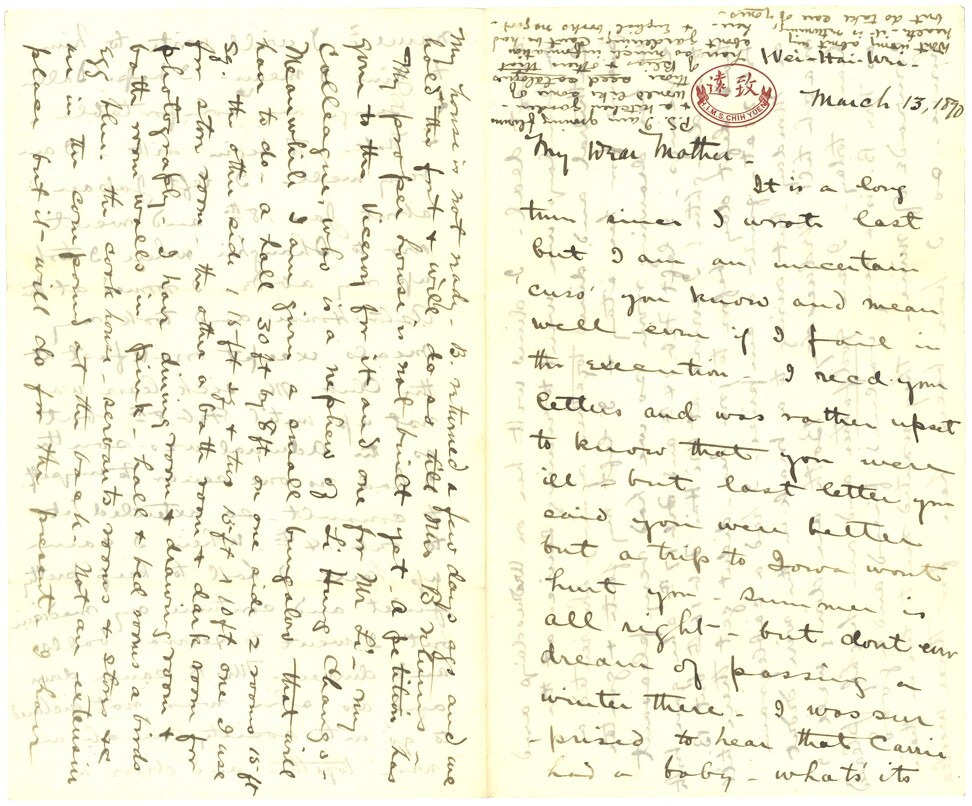

The collection of about 40 letters, photos, books and magazine interviews published during McGiffin’s lifetime reveal his impressions of 19th-century China and some personal details about him.

“Some people may not think that archives are a very exciting subject but McGiffin’s personal letters home to his mother run to 18 or 20 pages and say much about his work, the people he met, and also reveal that he was a very homesick young man,” Chu says.

In one letter to his mother, dated 13 April, 1885, McGiffin describes his arrival in Tianjin and his job offer from Li. “So here I am – 24 years old and Captain of a man-of-war – a better one than any in our own navy – only for a short time, of course, but I would be a pretty long time before I would command one at home,” McGiffin wrote.

He was paid US$100 a month and provided with an extremely comfortable house, close to the naval academy. “It has a long veranda, very broad; with flower garden, apricot trees, etc, just covered with blossoms; a wide hall on the front, a room about 18x15, with a 13-foot ceiling; then back another rather larger, with a cupola skylight in the centre, where I am going to put a shelf with flowers,” he wrote.

McGiffin also worked as a hydrographic surveyor on the Korean coast, helped oversee the construction of four warships being built in Britain for China, and was instrumental in the establishment of a dedicated school for naval training in Weihai, Shandong province, where he served as director from 1887. Hydrography is the science of measuring the physical characteristics of waters.

By July 1894, after persistent Japanese political interference in Korea, then regarded as a tributary state of China, war between China and Japan became unavoidable.

McGiffin postponed his long-awaited station leave to support the war effort. Like most observers at the time, he felt confident of a Chinese victory. Sir Robert Hart, the long-term inspector general of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, shared this optimistic view at the beginning of the conflict.

“If the war lasts long enough, we must win: Chinese grit, physique and numbers will beat Japanese dash, drill and leadership – the Japs are at their best now, but we’ll improve every day,” he wrote.

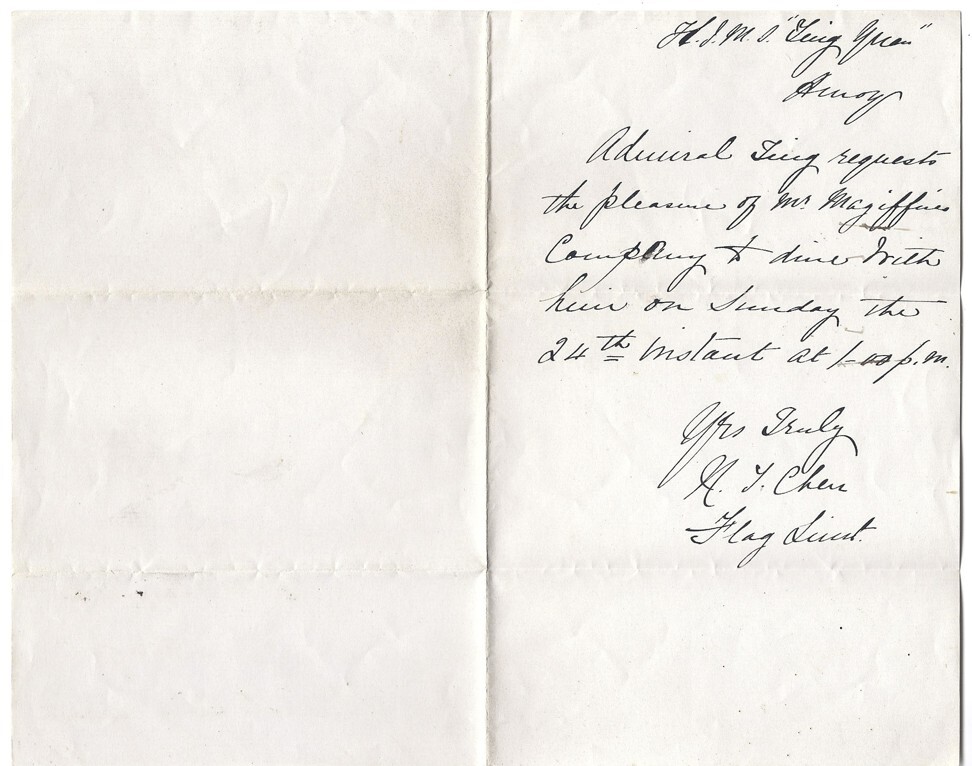

McGiffin was serving as commander and adviser of the Chinese battleship Chen Yuen under the command of Commodore Lin Taizeng. It was the sister ship to the flagship Ting Yuen, under the command of Admiral Ding Ruchang.

On September 17, 1894, the Chinese squadron was at anchor in the mouth of the Yalu River, which separates what is now North Korea and China. When the Japanese fleet was sighted, it presented the perfect opportunity to attack and stop Japan’s ambitions in its tracks.

Instead of a decisive victory, however, the Chinese forces suffered an ignominious defeat which led to an uninterrupted victory for Japan in occupying Korea and parts of the Chinese coast. McGiffin was badly wounded during the fierce exchange of gunfire.

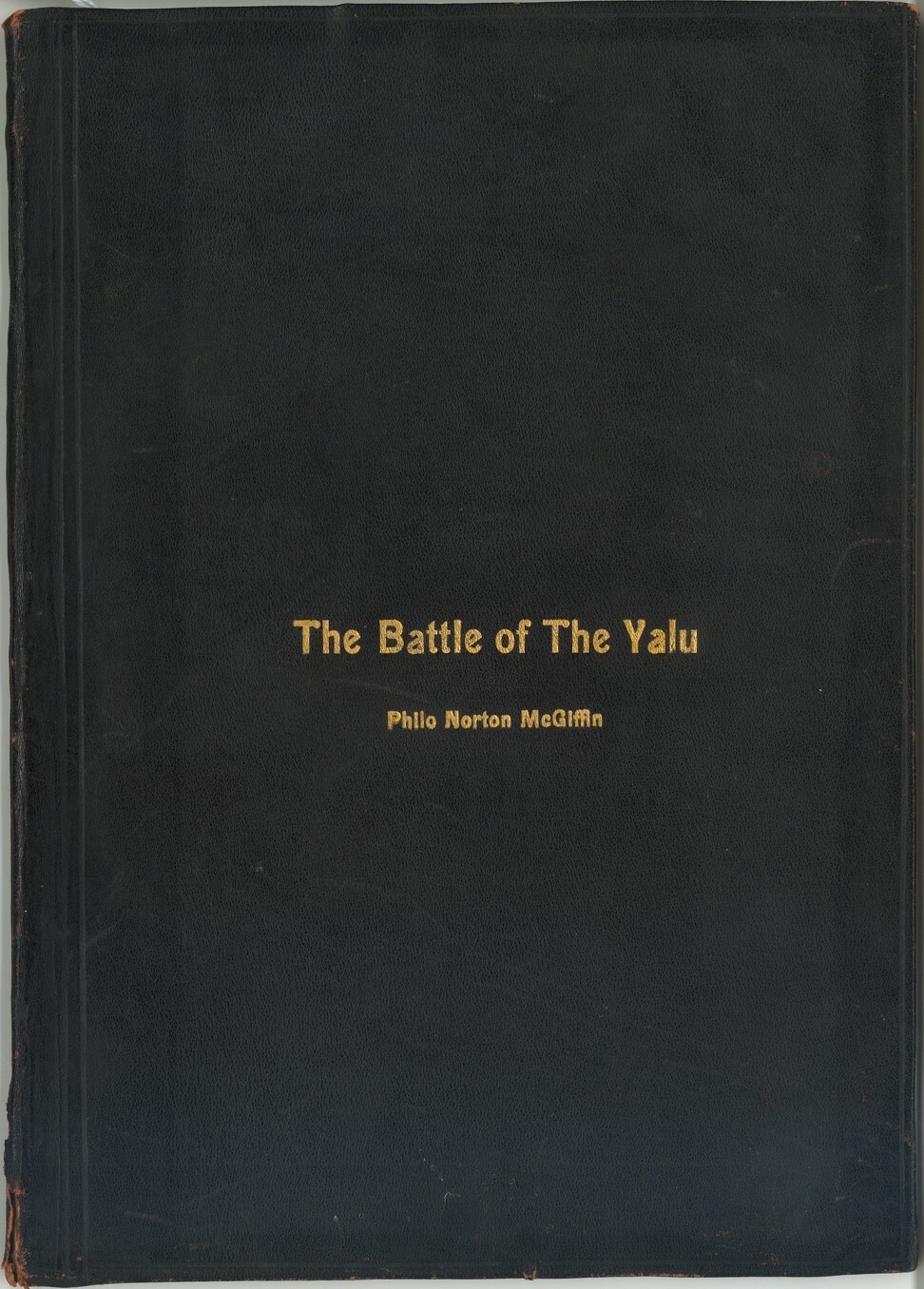

The events of that battle were recalled one year later by McGiffin in an interview with The Strand Magazine – also part of the archives and special collections along with his own published account of the battle.

The now-defunct monthly London-based magazine described McGiffin as “a tall, muscular-looking man with a strong, resolute face and an eye that indicates he would be a bad man to have as an enemy”, but by the time of the interview the captain must have been a shadow of his former self because of the crippling wounds he had sustained.

“How he ever came out of the engagement alive is a miracle,” the magazine noted.

The battle commenced at 12.20pm as the two Chinese battleships leading 10 warships opened fire with their 12-inch German-manufactured guns on the 13 Japanese vessels.

“The Japs soon replied to our music,” McGiffin told the magazine.

McGiffin’s lurid account of the battle and his barbed criticism of the conduct of some of his fellow officers has since been challenged by some scholars, but McGiffin was also complimentary about the actions of many of the ship’s company in action for the first time.

“On the whole I think our eight ships gave a very good account of themselves against the 13 Japanese vessels,” he recalled.

McGiffin was severely wounded while trying to lead a party of sailors to extinguish a raging fire on the forecastle of his ship, as his own guns fired over his head and enemy fire rained down on the burning deck.

“In the circumference of about a foot he seems to have been struck by at least from 40 to 50 pieces of shot or shell,” the article notes, and he also damaged an eye. Japan also put a price on his head of 5,000 yen and, in case of capture, McGiffin carried a vial of prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide) on him.

The accuracy of the account related in the magazine may be debatable, but McGiffin blamed the defeat on what he called “treachery in high places” and accused the First Lord of the Chinese admiralty of being in the pay of the Japanese.

Suicidal slaves, drunk translators – tales from Asia’s early travellers

There were insufficient shells and many had been filled with sand instead of high explosive charges. China had recruited Western experts and bought Western naval technology, but much of the deep-rooted Qing cultural traditions and rampant corruption flourished ashore.

Despite his extensive wounds, McGiffin safely navigated his ship to the port of Weihai in the east, where he sought treatment before returning to the US.

While undergoing further treatment in hospital in New York, his chronic pain became increasingly unbearable and his sight began to fail. On February 11, 1897, McGiffin called for a dispatch box containing his service revolver and took his own life, at the age of 36.