Hong Kong judges and barristers could wave goodbye to courtroom wigs in run-up to 2047, says city’s first chief justice

- Andrew Li predicts debates about continuing court dress code could emerge as city moves closer to end of Beijing’s 50-year handover pledge

- Barristers divided on subject of foregoing wigs, with some citing adherence to tradition, others calling headpieces impractical for busy lawyers

Silver horsehair wigs and long gowns have long been part of Hong Kong’s court attire for judges and barristers, passed down through generations as a part of its common law tradition.

The somewhat theatrical dress code also serves several practical functions: it is meant to deliver an image of solemnity, while also serving to distinguish levels of seniority among judges and barristers.

The tradition was retained after the former British colony returned to Chinese rule in 1997 to acknowledge a theme of continuity.

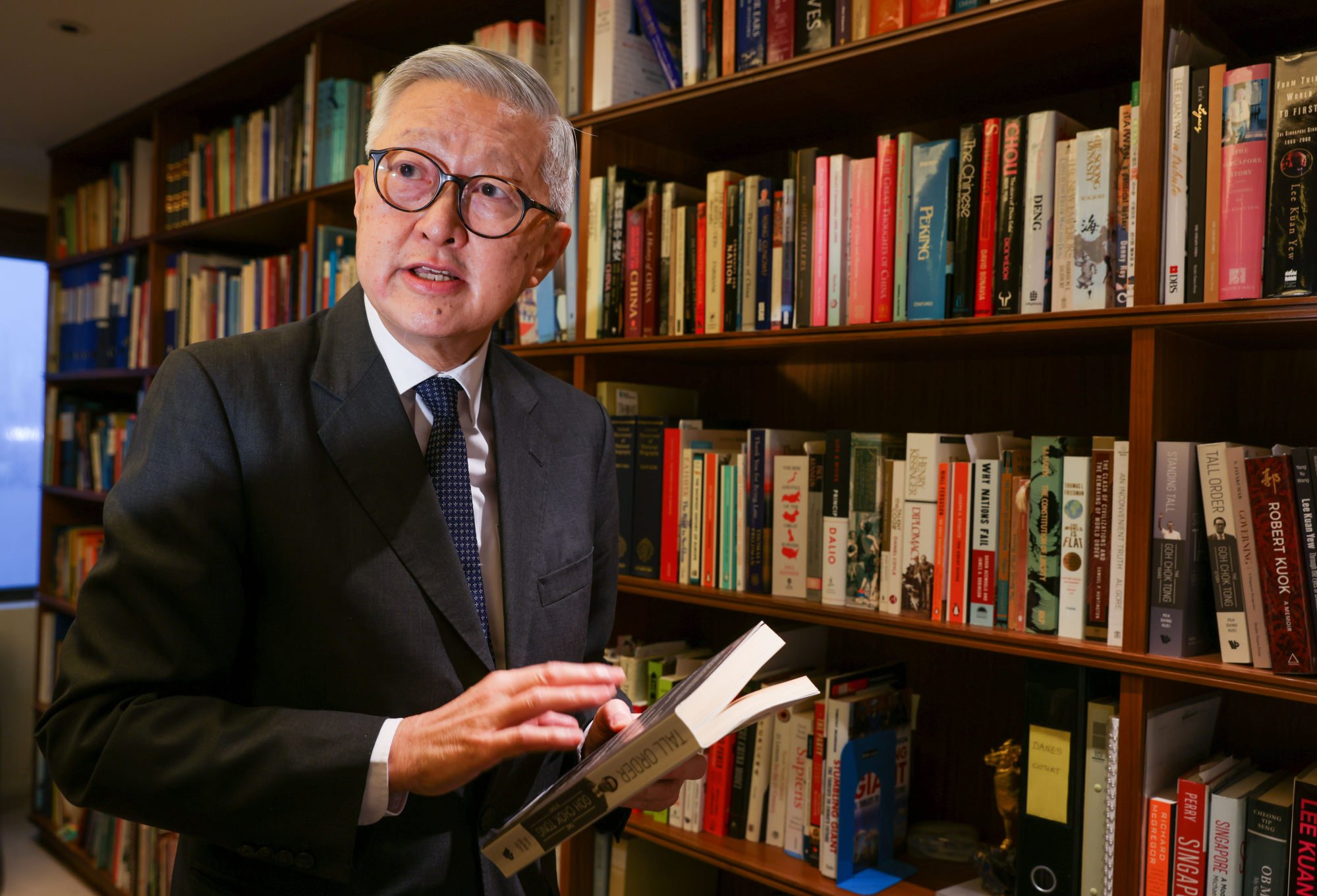

But the city’s first chief justice after the handover, Andrew Li Kwok-nang, has predicted that debates about continuing the convention were likely to emerge anytime in the run-up to 2047, the end of Beijing’s 50-year pledge of a high degree of autonomy for Hong Kong.

“There will come a time when it would be appropriate to discuss whether there should be a change in our court attire, in particular, whether the wig should be abolished,” he told the Post in an exclusive interview.

“I don’t think there must be change. I’m saying that this question should be discussed in due course,” he said. “There will be tension between tradition and modernity.”

Hong Kong barristers are currently required to wear wigs and black gowns at all courts above the magistracy level, except for the family court and at closed-door hearings.

An almost identical requirement applies to judges, except for the top justices from the Court of Final Appeal, where the wigs are exempted, while at the High Court, the colour of judges’ robes also shows whether they are adjudicating criminal or civil cases.

Li said that whatever the changes were, there should be uniforms for judges, explaining it would be conducive to “maintaining the dignity of the court and the judicial process”.

“Putting on the uniform would remind judges of their duty to adjudicate disputes fairly and impartially without fear or favour,” he said.

The wigs, which are derived from the headpiece worn by the English gentleman in the 17th century, are available to purchase at Jarvis and Kensington, a local shop selling legal wear in Admiralty.

A Hong Kong judicial tradition that’s worth keeping

Those who have a penchant for flair can even order them from judicial dress retailers based in the United Kingdom, such as Ede and Ravenscroft, which has a history dating back to 1689.

Prices can range from HK$2,000 (US$254) for a bar wig worn by junior barristers to HK$28,595 for the full-bottomed headpieces worn by judges and senior counsel on ceremonial occasions.

Most judges and barristers would usually use just one wig designated for a select role over a lifetime, while specialist dry cleaning services are offered at Jarvis and Kensington for HK$760 per headpiece.

“It is very uncomfortable wearing a wig in the summer,” said former chief justice Geoffrey Ma Tao-li, Li’s successor, who started his legal practice in Hong Kong as a barrister in the 1980s after graduating from a law school in the United Kingdom.

‘If everybody criticises you, you probably got it right’: Hong Kong’s former chief justice

Ma said he did not view the issue as an important one.

“If you said tomorrow that [the] chief justice would say: ‘No more wigs and gowns’, I don’t know anybody is going to really seriously oppose that.”

But he cautioned: “The only thing that concerns me is people who make a political point out of it.

“If you say: ‘Oh, we should finally get rid of any sort of links to the United Kingdom because the United Kingdom is not a friend at the moment. Therefore, get rid of all.’ That is being political … That is a bad reason,” he said.

Other common law jurisdictions, such as Australia and the United States, have long moved on from the practice of barristers and judges wearing wigs.

The Supreme Court in the United Kingdom also dispensed with the requirement for barristers to appear in wigs and gowns for civil cases in 2011. The top justices there have also done away with the attire.

A barrister, who asked not to be named, said lawyers were already carrying so many documents with them in addition to their wig and gown required for every court appearance.

“It’s based on convenience, not politics,” he said, adding the tradition could still be maintained at ceremonial occasions.

Hong Kong barristers given option of forgoing wigs for religious head coverings

Fellow barrister Azan Marwah, however, said he could see the benefits of preserving the tradition. Marwah co-led a campaign that resulted in the court in 2021 allowing barristers who practised certain faiths to wear religious head coverings, if needed, instead of a wig.

But he said that was an exception because it might stop some from wanting to join the legal profession, adding the tradition should remain so long as it did not obstruct the dispensation of justice.

“It is true that it adds to the gravity of proceedings. I think it does anonymise our argument of submissions,” he said, noting that the wig reminded barristers of their duty to the court regardless of their racial or economic background.

“I do think the sense of tradition and continuity of the legal style is very important at this point in Hong Kong history,” he said.