Diversity, enthusiasm … dentistry: Hong Kong literary festival lauded as one of the world’s best by authors

- For Pulitzer Prize winner Junot Diaz it was the diversity of the audience, for Louis de Bernières meeting a very tall Japanese woman and a dentist’s chair

- The festival’s 20th edition next month will make new memories – if for no other reason than that Covid-19 has forced the virtual staging of a lot of its events

Nothing, it seemed, could stop the literary-festival snowball: a permanently rolling, swelling agglomeration of 400 members and counting, now with its own global association.

This year, however, festivals great and small have found that they can be stopped by an invisible adversary – or obliged to adapt to Covid-19 to ensure the show goes on.

In April, Catherine Platt, former head of the literary festival in the Chinese city of Chengdu, joined the Hong Kong event’s organisers as director. While she has embraced the difficulties involved in presenting a radically different event to that envisaged early in the year, Platt recognises the festival’s history and resonance.

“I’ve followed the HKILF from a distance, but this is the first I’ve attended. I admired the way previous directors brought in major international names while also programming interesting events with local talent,” she says.

Then, sessions covered fiction and poetry only. Today, befitting its staging in a “world city”, the event is an 11-day jamboree encompassing genres and topics galore – although this time many participants will take part virtually. In reflecting on the festival’s evolution, Jane Camens, co-founder with Nury Vittachi, admits to certain reservations.

“If I were starting the festival now,” Camens tells the Post from Northern Rivers, eastern Australia, “I would conceptualise it differently. I’d hope to make it a hub for literary translation of work from Asian languages into other Asian and non-Asian languages.

“When I envisaged the festival I hoped it would inspire more writers in Hong Kong and elsewhere in Asia to write in English – and thereby find international readers. I now consider that a colonial world view and not a way to share work with any original soul with readers across Asia.

“It was always important to me that the HKILF presented writers from Asia, or of Asian heritage, or non-Asians writing about Asia – the last group enabling the expat population to take part,” she says.

“I think that these days, the festival should be run by locals keen to hear a variety of stories and points of view. I realise that with increased surveillance and/or self-censorship this might be difficult, but worth aspiring to.”

The draw for any literary bash is its author roster. And soon, a galaxy of established names and emerging stars began descending on Hong Kong – Jung Chang, Seamus Heaney, Margaret Atwood, Amitav Ghosh, Jan Morris, Ian McEwan, Miguel Syjuco, Benjamin Zephaniah and Anhua Gao to name just a few.

Recalling his sold-out appearances in 2010, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Junot Diaz tells the Post: “The HKILF still ranks as one of the most memorable and invigorating festivals I’ve participated in: supremely well curated, well organised and so enthusiastically attended. I’d never had audiences like those, from expat financiers to the humblest workers who commuted to the events each day.

“In the United States we love to talk about diversity, but the diversity of the HKILF made what passes for diversity at most festivals seem almost laughable. I met so many readers from every fraction of society. I could have spent a lifetime in those conversations – and kinda wish I had.”

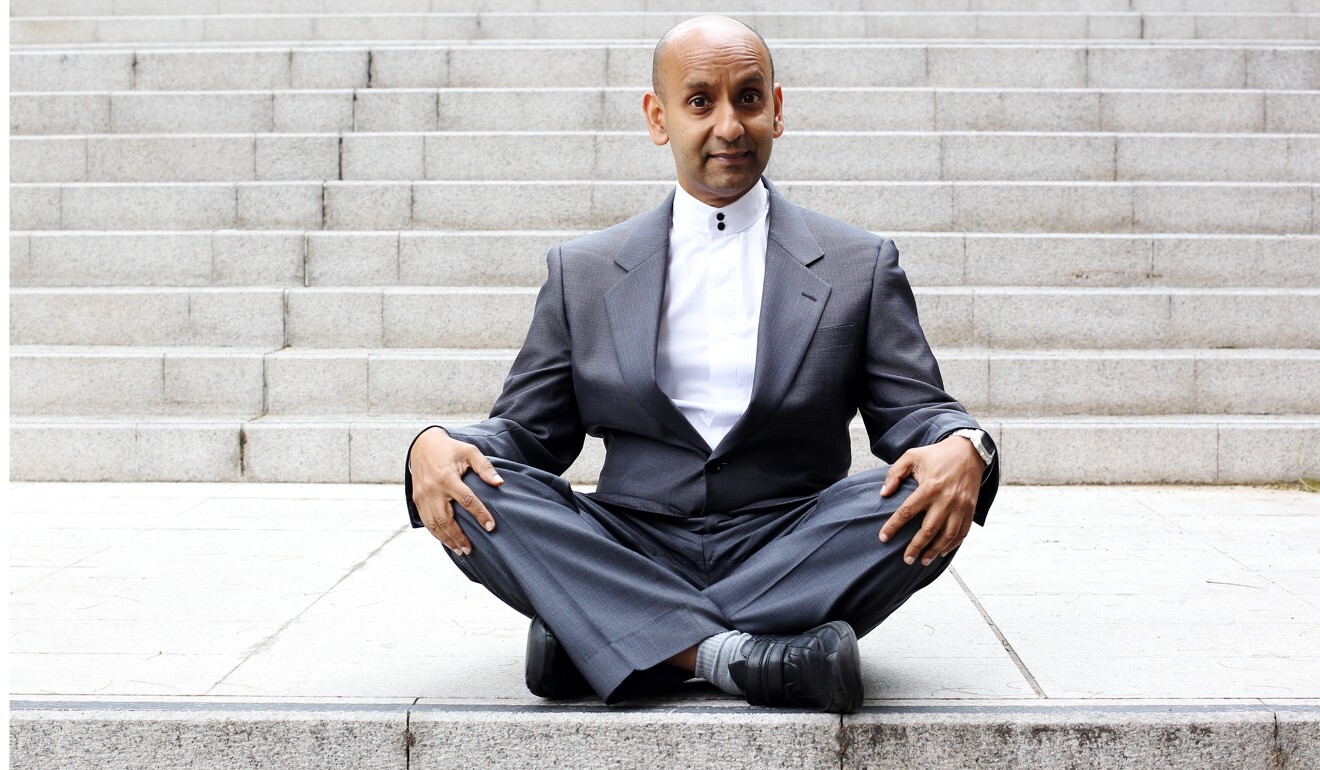

At the time of his appearance the same year, Mark Ravinder Frost, now associate professor in public history at University College London, had recently joined the University of Hong Kong, having held a senior position at the National Museum of Singapore.

“The HKILF was a turning point for me,” he reveals. “I’d written a history book [Singapore: A Biography] that had come out of a major public-history project I’d been involved in. I had taken an academic job but this wasn’t a conventional academic tome and I wanted it to be read by a general audience as a work of literature in its own right.

“When invited to do my session I didn’t expect anyone to show up,” he adds. “I wasn’t known and had never spoken at a paid event. Having a good audience, great questions and a brilliantly moderated discussion really set me on the path to craving more of this public-history thing.

“Being afforded space to read excerpts from the book was an entirely novel experience. To perform the prose I’d toiled over and feel the audience reaction was magical – something I’ve not felt in all the talks and lectures I’ve given since. The dynamic between reader and listener at the HKILF isn’t something you can replicate in these remote, Covid-19 times – no matter how good your ‘connection’.”

In the interests of full disclosure, this reporter has form with the HKILF, having had the pleasure of moderating events in all manner of venues during the course of many festivals.

Despite serving as books editor at the Post and editor-in-chief of the Asia Literary Review, and haranguing assorted festival board members and directors that they really should identify a permanent, centralised venue and stop scattering “gigs” across the city in places unlikely ever to be found on Google Maps (such as an obscure Spanish restaurant), he didn’t have enough clout to push a Tai Kwun Centre into the reckoning.

Imagine his surprise when the old Victoria Prison in the city’s Central district finally became the unofficial HKILF headquarters – its biggest claim to infamy to date concerns the on-again, off-again appearance of Chinese dissident novelist Ma Jian in 2018.

The festival’s patronising of unlikely venues saw the UK’s future poet laureate, Simon Armitage, gamely tackling a session above a Wan Chai pub in 2012. The event was undersold and the sparse crowd hardly in the mood for poetry.

At least they were well lubricated – unlike the technical equipment, which came with only one functioning microphone of the three provided.

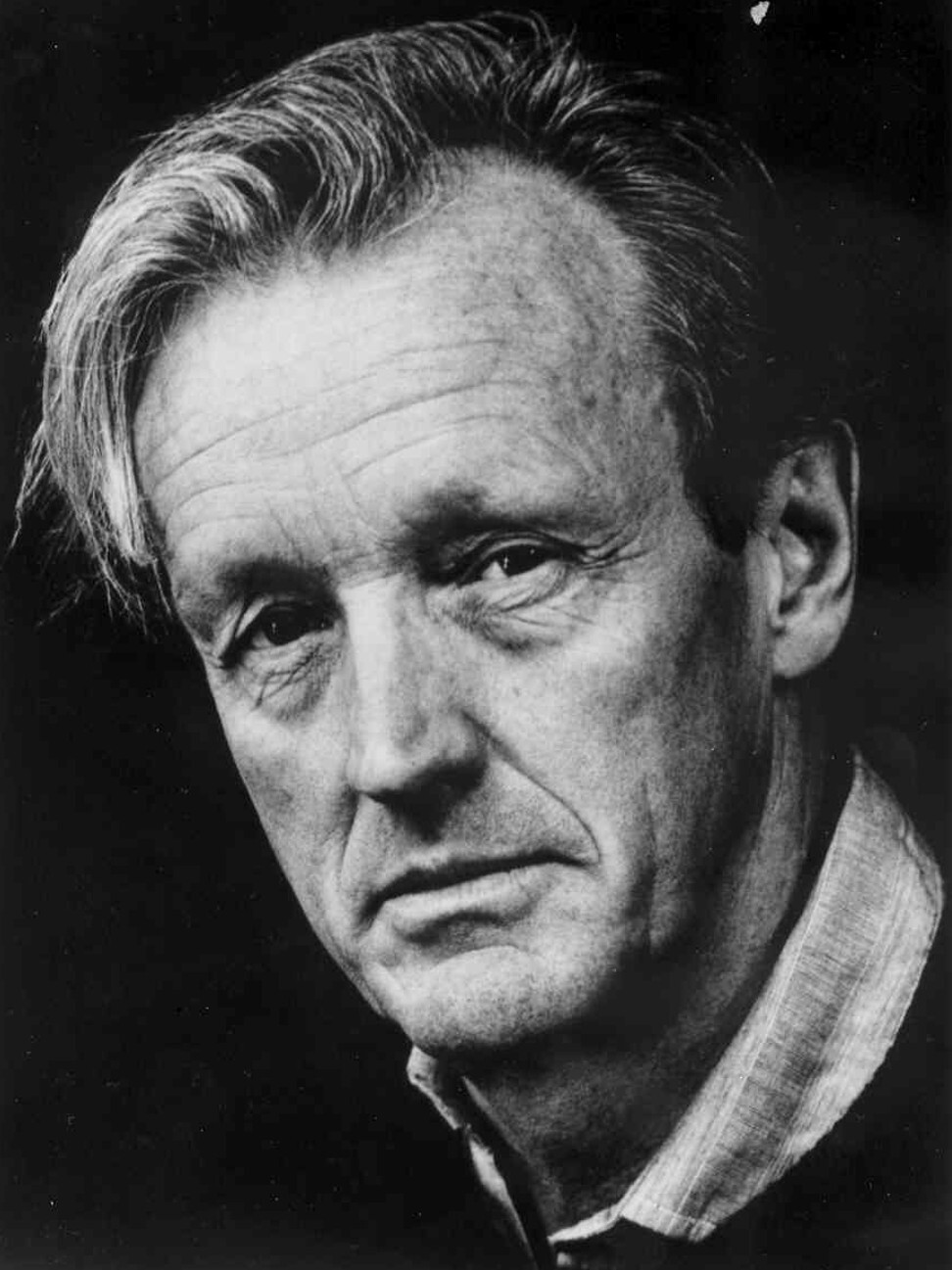

Then again, a penchant for quirky venues did permit this reporter a moderating debut at much-missed restaurant-salon M at the Fringe, in 2008. The star turn was novelist and revered travel writer Colin Thubron, whose lordly gravitas would surely leave a first-time microphone swinger like me floundering out of his depth.

The urbane Thubron, in fact, could hardly have been more accommodating, patient and generous with his lifetime of worldly insights. (Footnote: two metres from the speakers’ desk at that event sat Dava Sobel, a popular-science publishing phenomenon thanks to the chart-busting Longitude. This moderator took the opportunity afterwards to ask her exactly how to pronounce her name – only to earn a mild public rebuke some days later by mangling it at an oversubscribed event at The Fringe Club.)

The impressions made by a festival can long remain with its writers. Headliner Louis de Bernières, author of many novels besides his most celebrated, Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, has numerous colourful recollections of his HKILF appearances a decade ago – and not all are literary.

“I mainly remember a fabulous dentist who took out a wisdom tooth, and Stanley Market, and a very tall Japanese woman I liked a lot. Also, interviewing myself when the interviewer was late,” he tells the Post.

“The dentist was projecting [Rudolf] Nureyev and [Margot] Fonteyn, in Swan Lake, on the ceiling. I was so captivated I didn’t notice her doing the operation; it was over while I was still waiting for it to start. In Stanley I bought a velvet jacket each for me and the children. We called them our Emperor Jackets. And although the Japanese woman’s name escapes me, I do recall that she took me for my first Japanese meal. And that she said she was dumping literature to go and work for Goldman Sachs.”

The 20th Hong Kong International Literary Festival, November 5 to 15. See festival.org.hk