European disunity on China won’t smooth the path ahead

- Brussels has sought to bring the bloc together around a stronger policy towards China, as Beijing’s influence grows across Europe

- However, there are clear differences between hawkish Eastern European nations and Western European economies which do more business with China

Former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger is widely credited with saying: “Who do I call if I want to speak to Europe?” This famous question has been repeated often over the years to highlight the lack of a unified foreign policy across the continent.

The implication here is that there could be significant benefits for foreign powers if they could speak to a single interlocutor for the European Union. However, an increasingly common criticism in Europe of China is the opposite: namely, that it favours a splintered EU so that it can “divide and rule” across the continent.

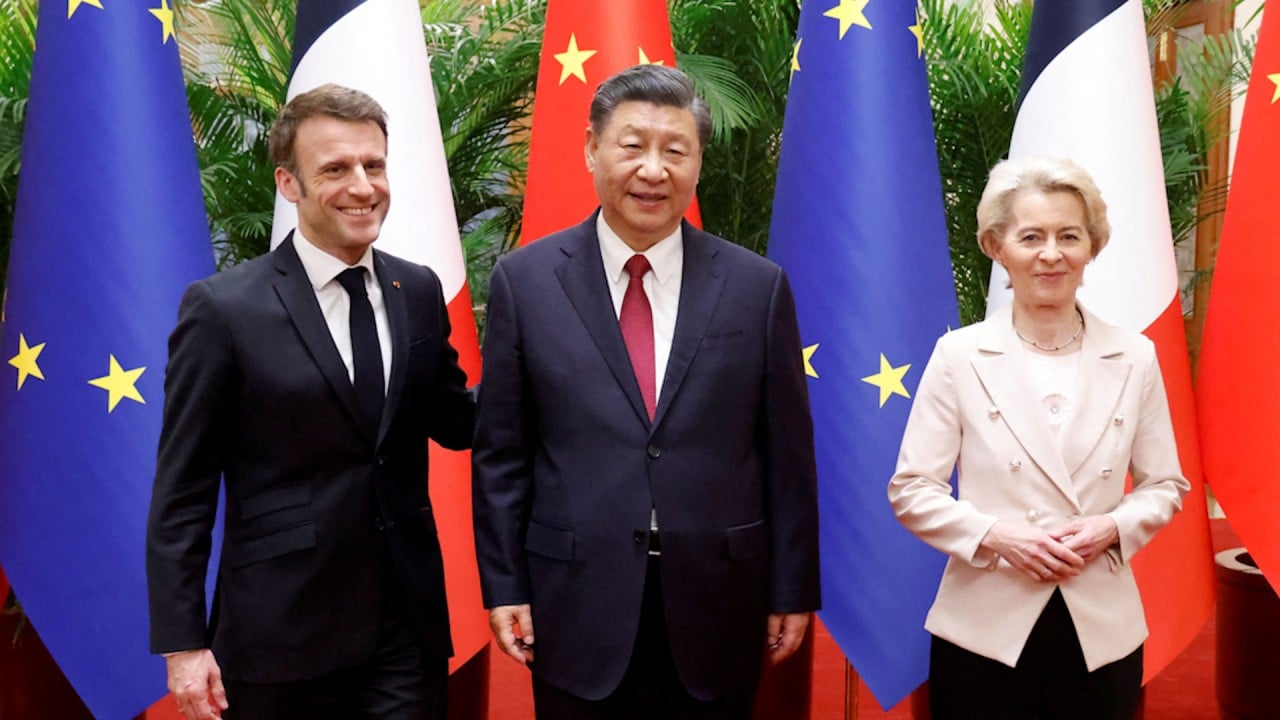

The summit comes as European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen and other top EU officials such as foreign policy chief Josep Borrell attempt a unified, bloc-wide stance towards China. Yet, despite its efforts, Brussels is struggling to find common ground on Beijing across all 27 member states.

Top EU officials have become increasingly concerned in recent years about whether China’s interventions in Europe represent a “divide and rule” strategy to undermine the continent’s collective interests. Europe is becoming an important foreign policy focal point for China which had, until the pandemic, enjoyed growing influence across much of the continent.

Following the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Brussels has sought to bring the bloc together around a stronger policy towards China. Von der Leyen and Borrell have led on this, even though the European Commission president does not have a formal foreign policy role.

EU policy on China is clearly moving in a more hawkish direction. Yet, a central challenge for von der Leyen and Borrell is that the 27 member states don’t agree on China.

Despite ‘de-risking’ talk, Scholz’s Germany has not turned away from China

Perceptions of a divided Europe have also been publicly highlighted by Chinese officials including Fu Cong, the ambassador to the EU. Fu recently said a speech by the European Commission president gave him the impression that “Europe has not formulated a coherent policy toward China”.

Perhaps most surprising of all was Macron’s shift on Taiwan. Whereas von der Leyen asserted during the trip that “stability in the Taiwan Strait is of paramount importance” and that “threat of use of force to change the status quo is unacceptable”, Macron marked his departure from China by describing Taiwan as a crisis that is “not ours” and as a topic on which Europe should not become “America’s followers”.

Taken together, this forms a challenging backdrop to this week’s summit. It is not just that EU-China relations are frozen, but that they could yet go from bad to worse in 2024.

Andrew Hammond is an associate a LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics