Ukraine war: the world is staring at mutual assured destruction

- Austrian scholar Friedrich Glasl’s model of conflict escalation tracks how disputes deteriorate from tension to total destruction

- In the nuclear age, it is vital for political leaders to come to their senses and choose diplomacy, not war

Back in 2021, the US National Intelligence Council’s report, Global Trends 2040, put it thus: “In coming years and decades, the world will face more intense and cascading global challenges ranging from disease to climate change to the disruptions from new technologies and financial crises.

“These challenges will repeatedly test the resilience and adaptability of communities, states, and the international system, often exceeding the capacity of existing systems and models. This looming disequilibrium between existing and future challenges and the ability of institutions and systems to respond is likely to grow and produce greater contestation at every level.”

In short, we are having trouble figuring out how to deal with the crises we face. Each challenge could cause fragmentation as resources are unevenly distributed, and would require hard choices.

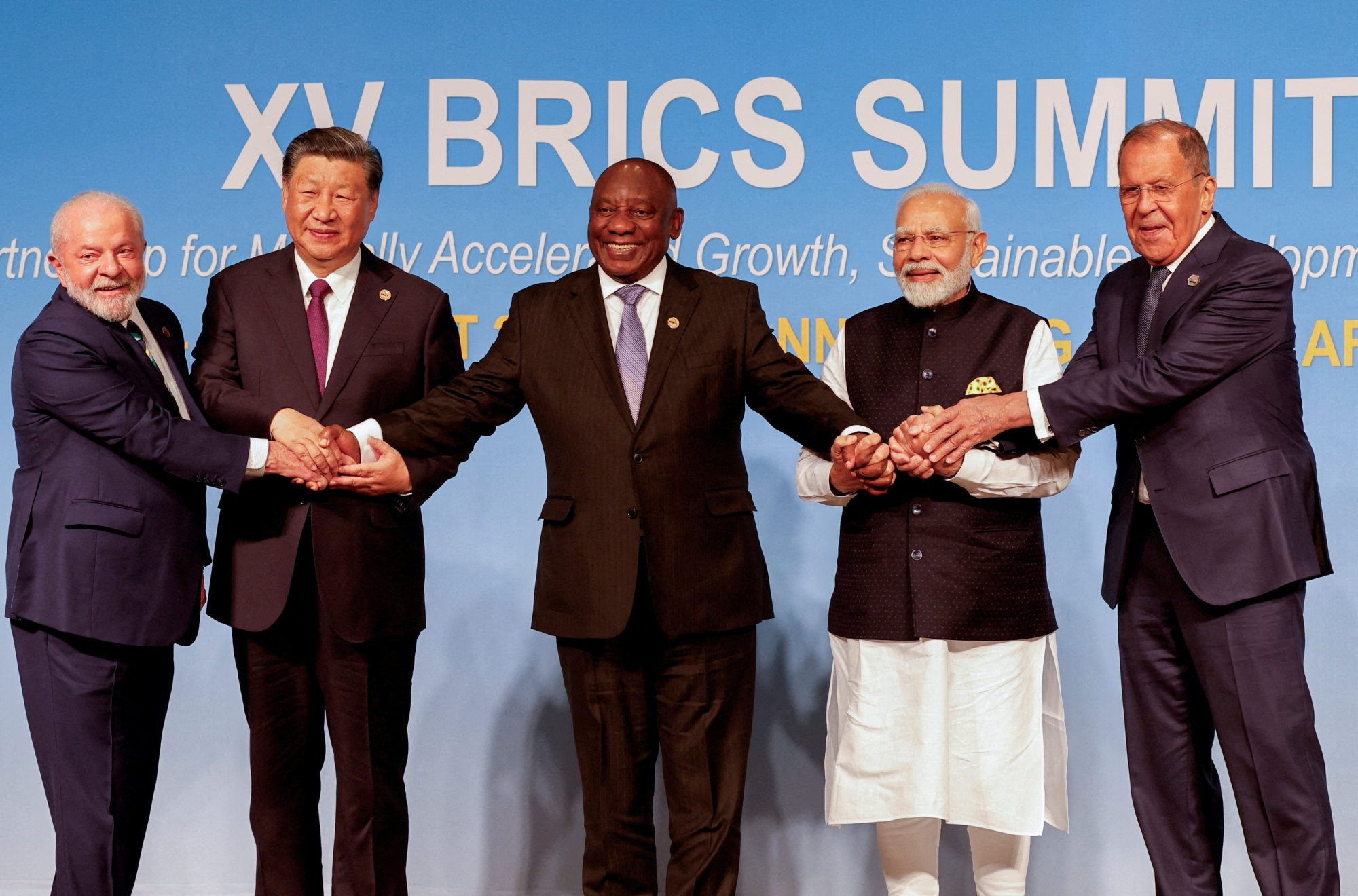

The enlarged Brics will account for 37 per cent of the world’s GDP and 47 per cent of its population, compared with 9.8 per cent of population and 29.8 per cent of gross domestic product for the Group of 7 (i.e., six rich Western countries plus Japan).

The Brics bloc is also more inclusive and diverse; more importantly, it is not a military alliance. Instead, it is a group of emerging economies, including former colonies, which are not about to swallow Nato, G7 or Western preaching about democracy and the rules-based order.

Ukraine war: West must accept the liberal order is gone for good

Interestingly, Austrian scholar Friedrich Glasl has developed a nine-stage model of conflict escalation. In this model, the nine stages of escalation are divided into three levels: level 1, where a win-win deal is within reach for both sides; level 2, where one side wins and the other loses; and level 3, a lose-lose situation for all.

Every conflict begins in stage 1, at the win-win level, with tension growing between two parties. Stage 2 is when the two parties debate and disagree. In stage 3, the conflict goes beyond words to actions.

In stage 4 at the win-lose level, each side tries to find allies and form a coalition to bolster its position. At stage 5, one side tries to make the other lose face. In stage 6, threats are made and then carried out.

Stage 7 is when the conflict deteriorates to the lose-lose level; at this point, one side is ready to suffer limited losses, if it causes more damage to the other side. At stage 8, the opponent has to be destroyed by all means possible. And if the conflict is allowed to progress to the final stage, when one side must destroy the other even if it means destroying itself, everyone will lose: in other words, it will be mutual assured destruction.

Further to this, Glasl regards the Ukraine war as three entangled conflicts: a geopolitical tussle between the West and the rest of the world, an interstate war between Russia and Ukraine, and a intra-Ukraine conflict between pro-West and pro-Russia groups.

However, Glasl’s model of escalation suggests that conflicts can be reversed, if both sides can seize windows of opportunity to de-escalate and move from military action back to diplomacy. The fundamental lesson here is that there are two sides to a situation, and we must learn to consider it from the other side’s perspective.

As we should know after two world wars, conflicts are volatile tangles of logic and emotion, and a small incident – the assassination of Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand, for example – can lead to a rapid mobilisation of troops, and war. Yet, it is easier to enter into war than to exit it.

Peace can only come when political leaders come to their senses and the realisation that war only leads to more war. In the nuclear age, warfare could end in the destruction of all.

Political leaders must climb down for peace, or face the collapse of everything, economically, politically and existentially. There is no victory to be won in nuclear war, nor will there be a status quo to return to. This is why peace is the only real option.

Andrew Sheng is a former central banker who writes on global issues from an Asian perspective