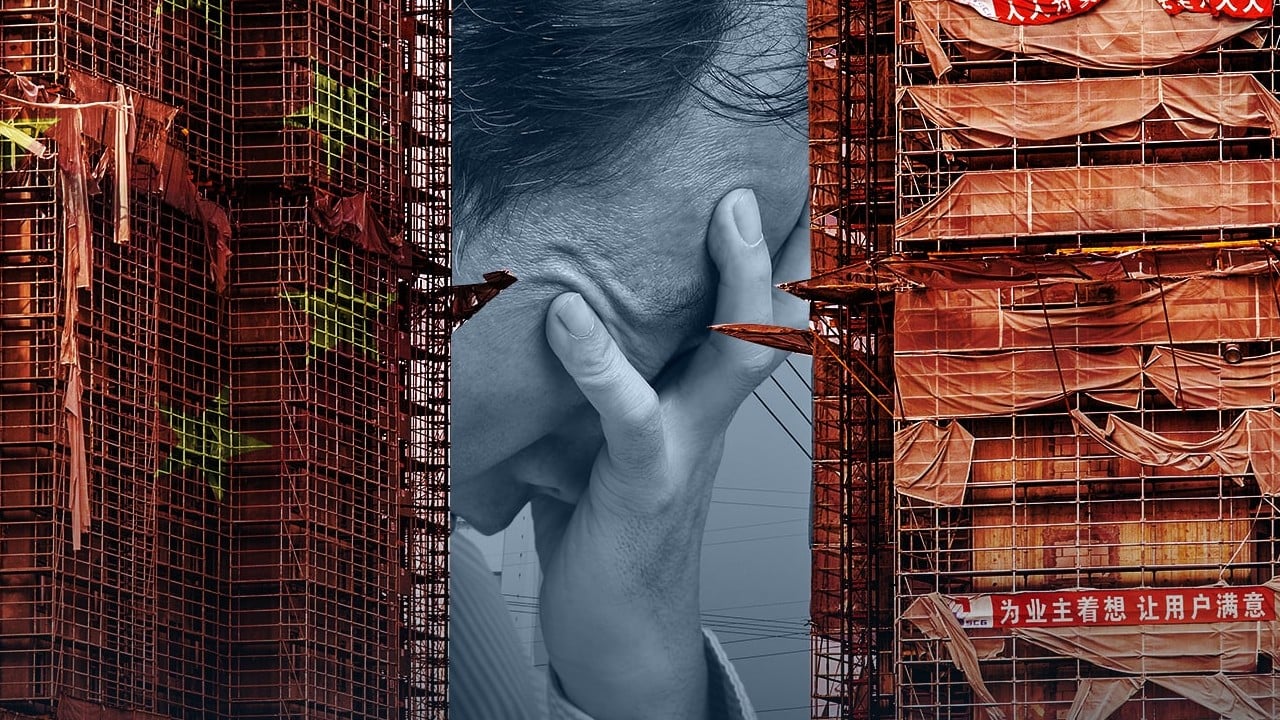

Investors keep wary eye on recession risks and China’s confidence woes

- There is a shared view among investors across Asia that developed economies face moderate recession risks after a year of monetary tightening

- On China, investors’ focus is squarely on the struggles of its post-Covid recovery, weighed down by poor consumer confidence and property market concerns

This is reflected in their investment stance. Most people do not have an overweight position in equities. Fixed income is viewed more favourably with a peak in interest rates in sight. Also, there is a common view that no major asset allocation decisions are likely when cash offers a reasonable return and credit and equity markets are not seen as particularly cheap.

The performance of equity markets was widely discussed. Most investors seem surprised at how strong returns have been, particularly when the default macro view is that a recession might be on the horizon.

Non-technology experts understandably do not see all the potential benefits and risks from AI, but they seem sympathetic to the view that it has the potential to provide non-linear growth for those businesses directly in the AI supply chain and those that are able to use AI to boost productivity and profitability. At the same time, few investors want to chase the AI frenzy when all other macro indicators are negative for short-term equity returns.

My trip started in Australia. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has been raising interest rates since May 2022, taking rates from close to zero to a current target for the cash rate at 4.1 per cent. Market expectations are for the RBA to take rates to around 4.5 per cent.

‘It’s never been this bad’: what’s behind Australia’s looming mortgage crunch?

This is good for Aussie bonds – the current benchmark 10-year bond trades with a yield of more than 4 per cent, just shy of the highs it reached in 2022. These are decade-high yields at a time when inflation is falling and thus are attractive for local pension and insurance funds.

There is clearly a risk of declines as housing finance conditions tighten. Is that enough to cause a recession? The forecast for GDP growth in 2024 is around 1 per cent, so a modest recession is very much on the cards, especially as commodity prices have also fallen this year, hitting revenues to the mining sector.

China’s post-Covid economic health check

In the longer term, there are interesting things happening in terms of the green transition in China and around the country’s need to respond to the controls put on its technology exports. These will provide potential opportunities in Chinese equities, but the near-term macro outlook and the uncertain geopolitical outlook will provide major hurdles to inflows.

Chris Iggo is chair of AXA Investment Managers Investment Institute and chief investment officer of AXA IM Core