Game strategy shows there can be no good outcome in the US-China-Russia power contest

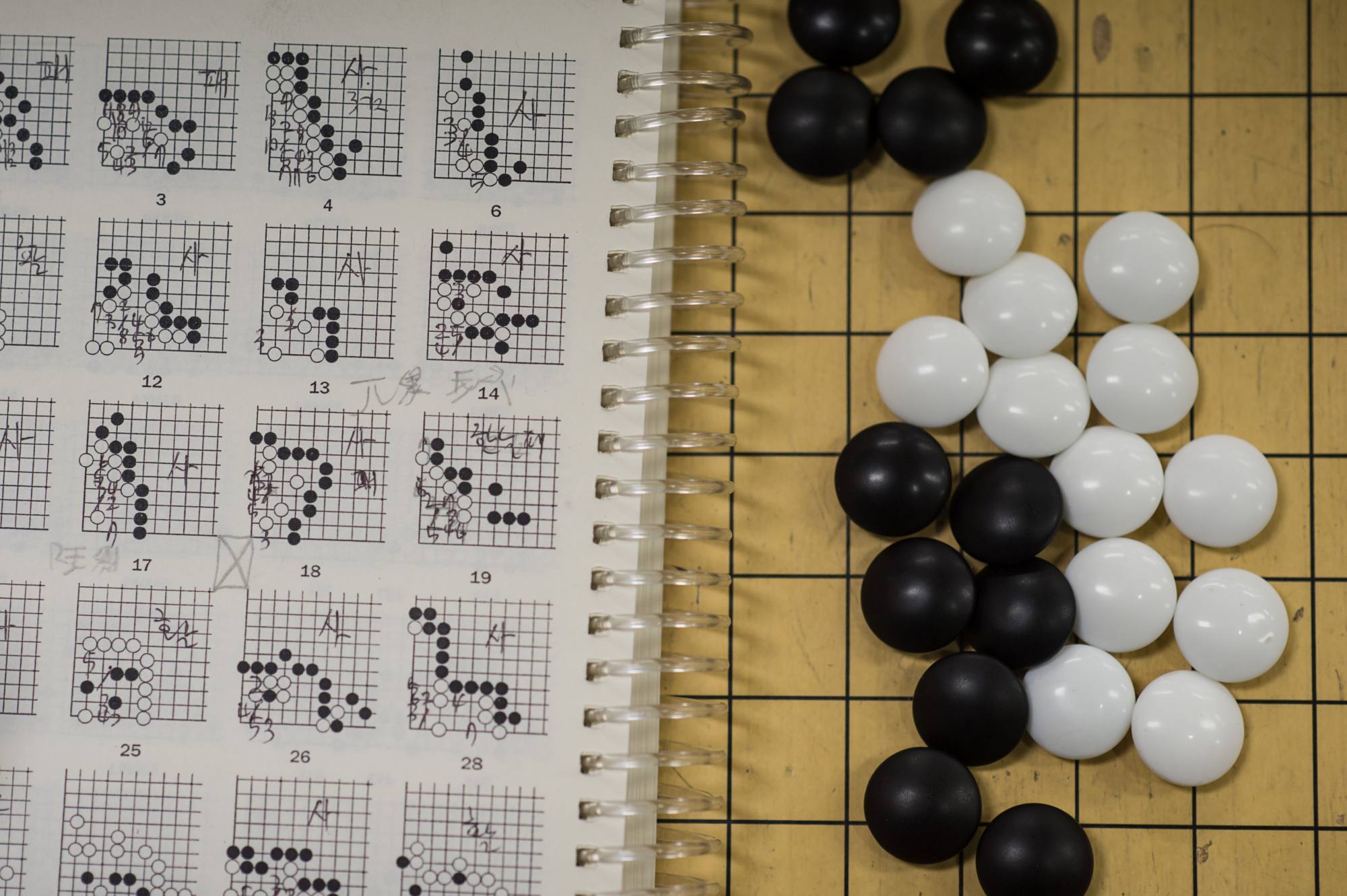

- The war games being played by the US against its two rivals are a combination of chess and Go, in which it must anticipate its opponents’ moves while claiming as much space on the board as possible

- Such a complex game can only end in negotiations with no clear winner, but much damage may be done before then

The current geopolitical scenarios are so scary that we need new narratives to try and understand where it will all end – nuclear annihilation or climate burning?

Games are imitations of real life. They teach players to read their opponent and anticipate his actions, with better players learning to appreciate how their opponent reads them.

So, back to how a player reads the game, and how the others read him.

The kiddie’s game of draughts teaches players to think linearly, but smart players quickly learn that if you offer the other side a quick win and he takes it, you crush him by thinking several moves ahead of him.

The game of chess is much more complicated, with pieces that have different power, and can be promoted (e.g. pawn to queen). The moves are intricate, with psychology and stamina key to winning.

The game of Go, popular in the East, has only black or white pieces, but is yet more complex, because you have to think spatially, manoeuvring your pieces to outwit your opponent.

But the smartest of weapons can be wielded by dumb users, leading to accidental conflicts. We are in that dangerous phase right now.

The Ukraine war is a massive tragedy, because from a practical point of view, Ukraine will pay for that principle to the last Ukrainian. The underlying US objective of the Ukraine war is to weaken Russia, as revealed by US Secretary of Defence Lloyd Austin.

History teaches us that all wars, just or unjust, end in negotiations, so that war is a way to strengthen your bargaining position for the best, or least worst, outcome. Principles give way to pragmatism. In the nuclear game, either you negotiate or everyone gets annihilated.

In the geopolitical board game – a mix of chess and Go – the question in essence is whether the West (Nato and allies) can contain the rise of its perceived “existential” rivals Russia and China. The Rest will decide who has the upper hand.

It is too early to tell who will win. Population-wise, the West has 1.2 billion out of 8 billion, whereas China and Russia have 1.5 billion and the Rest 5.2 billion. The West is rich in terms of GDP, and if you combine land area plus exclusive economic zones, the West has 46.4 million sq km, compared with 35.9 million for China and Russia. The BRICS countries have a combined 53.5 million sq km.

The Ukraine war revealed that Russia is not merely a “gas station” with the GDP of Texas. It is a nuclear power with the largest land area in the world, with everything it needs in terms of food, energy and mineral resources. China has economic and people clout, but lacks natural resources to power its economy.

This global rivalry is already becoming a hundred-year marathon, not a quick win for anyone. Europe and the Rest will side with the winner. Europe is now clearly deeply weakened by the Ukraine war, having its supply of cheap food, energy and mineral sources cut off by the alienation of Russia.

Biden is pushing China towards a conflict it doesn’t want

America remains the fortress defended by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. But how long can it maintain the largest military in the world if the global economy moves into recession?

War cannot be the solution to global peace and prosperity. War and more defence spending will not get us out of climate warming, inflation, debt distress, financial crises and job disruption from technology.

There is no endgame in war, only wealth and health destruction. Better sense will prevail when everyone loses sufficiently from the fever of war and get back to practical living with each other. The geopolitical board game is not going to end any time soon.

Andrew Sheng writes on global issues from an Asian perspective