The greatest challenge facing China’s chip drive? It’s neither funding nor talent, but resource allocation

- China can plug the talent gap by revving up its universities and use its powerful state apparatus to pool semiconductor funding

- But getting the resources channelled to the right companies and minds is a path riddled with subsidy fraud, R&D incompetence and corruption

Yet there are differences between China’s semiconductor industry today and Japan’s then. In the 1980s, Japan accounted for more than half of the global semiconductor market. China had just 4 per cent of the market in 2021. Even so, Washington has decided to stifle China’s semiconductor industry, from the upper to the lower reaches of the supply chain. Its chip sanctions on China are far worse than those unleashed on Japan decades ago. It appears Washington is determined to snuff out the industry in China before it fully matures.

Beijing is clearly unwilling to be a sitting duck. But as a more vulnerable competitor, China can expect a tough journey.

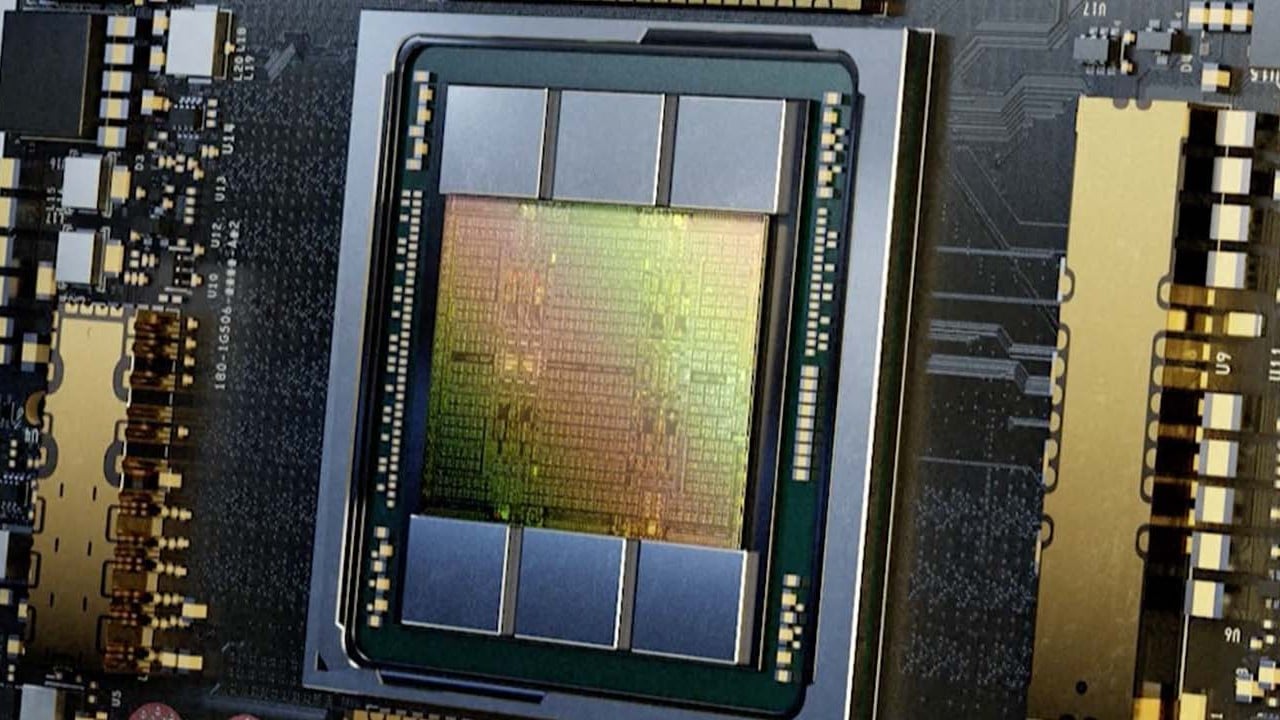

In 2021, the combined revenue of China’s top 50 semiconductor companies was only US$40 billion – half of Intel Corp’s US$79 billion. Accordingly, Chinese companies are limited in what they can spend on research and development. For instance, Intel spent US$15.2 billion on R&D in 2021, three times the revenue of China’s top chip maker SMIC.

Given China’s huge population and strong economy, its talent and capital shortages will not last too long – its real challenges are in resource distribution.

Firstly, how can the government make sure that resources go only to qualified entities? There have been fraudulent applications for subsidies, and some companies are simply incompetent at R&D. Giving them resources will only result in waste and losses.

Jinhua had been collaborating with Taiwan’s United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) on DRAM chip development. However, the DRAM development team was located in Taiwan. After Jinhua was sanctioned by the US, UMC backed out of the cooperation deal and Jinhua had to stop production with little to show for its investment.

If government funds are reduced to a hotbed of corruption, Beijing’s hope of breaking free of US chip sanctions will crumble.

Beijing must take a good, hard look at its institutional flaws at every stage of industrial policy implementation, from qualification verification and project approval to financial transparency – and make timely adjustments.

Otherwise, these are serious problems that could stand in the way of China’s efficient use of talent and capital in its semiconductor self-sufficiency drive, and could risk ruining the virtuous industrial ecosystem.

Chengxin Zhang is a doctoral candidate at the School of Politics and International Relations of Lanzhou University, China, and a researcher at the Youth Think-Tank of The Glory Diplomacy of China