US-China chip war: history shows that mercantilism is no solution

- Neo-mercantilism initiatives in China and the US, with their enormous investments and unprecedented trade restraints, will take years to show benefits

- Yet much will change that could render this generation of semiconductor plants obsolete the day they open

The resurgence comes after the system waned in the late 18th century following 250 years of dominance. Mercantilism had flourished in a period that saw feudal estates succumb to consolidation within nation-states. Shipping capacity grew, allowing international trade to surge. Industrialisation revved up in response. Fewer barter payments were used. Economic nationalism – bolstered by military force – accelerated those trends.

Mercantilists viewed wealth as static or fixed. To amass wealth, your country had to reduce others’ riches. By exporting more than you imported, you earned foreign-exchange surpluses to buy precious metals.

To boost exports and achieve full employment, thereby quieting the masses, governments exempted certain businesses from laws and taxes. Monopolies had free rein. Trade restraints blocked competing imports while cartels ensured high prices and tight supplies. Skilled labour, capital and tools were banned from emigrating. States generated revenues by selling monopoly privileges and then siphoning off part of the companies’ profits.

Today, as growth slows rapidly worldwide, we’re seeing similar measures with greater frequency and intensity – especially in digital technologies – emerging with the rise in economic nationalism, as part of a nascent world order.

Mercantilism came under fierce attack in its last century of pre-eminence. The economist David Hume (1711-1776) argued that labour and commodities can generate unlimited wealth, that money is only a means of exchange. Hume advocated free trade because our innate nature requires us to be “dependent on each other”.

But it was another contemporary, Adam Smith, writing in his monumental The Wealth of Nations (1776), who delivered the most vigorous call for laissez-faire economics. Mercantilism obstructs the efficient division of labour, which allows us to specialise in what we do best and trade with those who have mastered other goods and services we need.

Free trade improves society’s living standards by leveraging comparative advantages. Europeans found these ideas liberating after suffering from centuries of imperialist battles.

Those 250 years, though, also showed rulers’ vagaries in managing economies. Short-term expedience, if not corruption, overtook long-term strategies. Demand for raw materials in foreign lands necessitated colonialism and its abuses.

Hong Kong must wrestle with Britain’s colonial legacy, not romanticise it

Rulers’ supporters were enriched; opponents weren’t. In markets protected from competition, the risks were minimised such that businesses grew profligate and lazy, inflating prices and cheapening quality for captive consumers. Inefficiencies corroded the system, wasting capital.

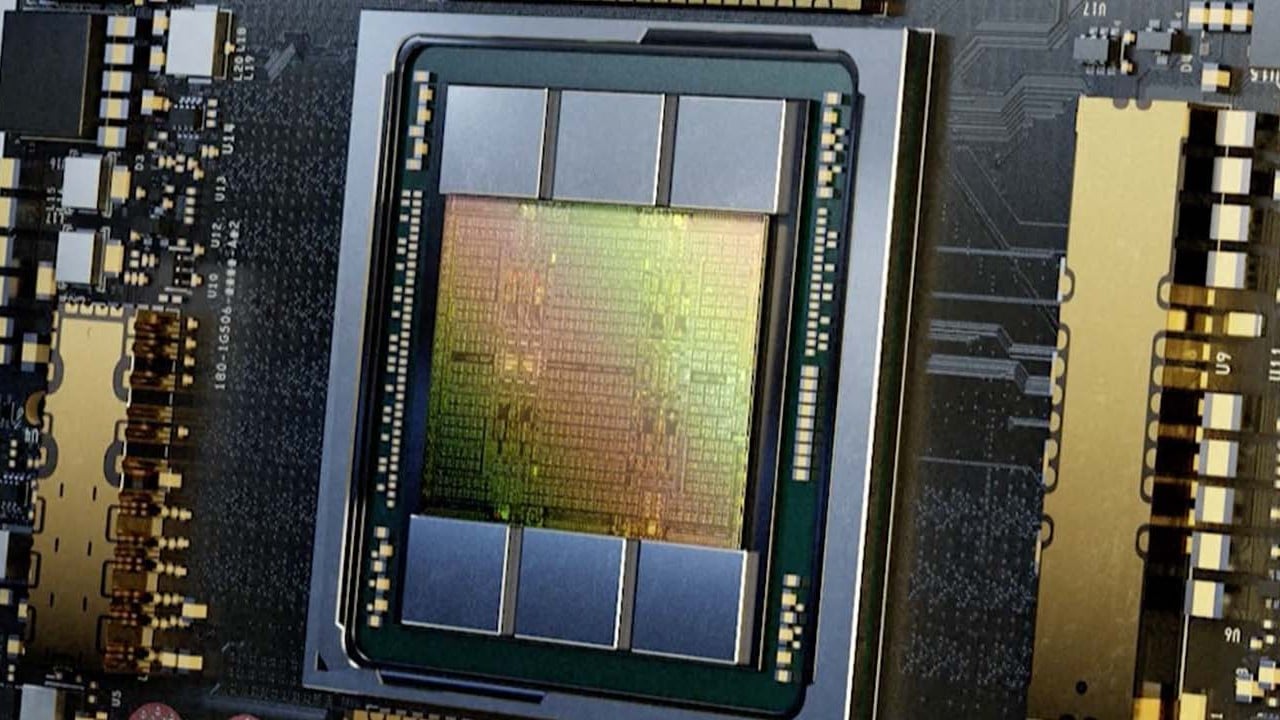

To meet the shortfall and achieve hegemony in developing and manufacturing chips, China and the United States have adopted neo-mercantilism, which some call decoupling, a move away from interdependence towards “bifurcated” technologies.

Yet, after more than 30 years of support, mainland Chinese semiconductor companies make up a relatively small part of the “fabless” (design only, production outsourced) global market, between 10 per cent and 15 per cent, depending on data methods, according to IC Insights, the Semiconductor Industry Association and others. The US, South Korea and Taiwan dominate. But China consumes more than three-quarters of semiconductors sold globally, roughly US$300 billion.

US is destined to lose the chip talent war with China

Will neo-mercantilism – the enormous investments and unprecedented trade restraints – rescue both countries? The answer is mixed, but only a temporary fix at best if history provides our answer.

Trade in technologies is fraught with enormous subsidies, restrictions justified on national security grounds, ever-shortening product life cycles, and, recently, the world economy’s slowdown. China has expended an enormous amount of capital yet remains a small producer, heavily relying on foreign suppliers for its chips. That has diverted investments from agriculture and sustainable energy.

The US lead is narrowing as Asia’s producers increase their shares. Both countries’ initiatives will take years to show benefits; a new plant takes roughly three years to build and operate. Much will change that could render this generation of plants obsolete the day they open. Governments are not nimble, their expertise haphazard, and their political compulsiveness worse than a CEO’s nervousness over quarterly earnings.

Mercantilism’s past is one of few gains and enormous costs. A rerun is likely.

James David Spellman, a graduate of Oxford University, is principal of Strategic Communications LLC, a consulting firm based in Washington, DC