Ukraine crisis: is there reason to be optimistic about peace?

- On the matter of Russia and Ukraine, Beijing has been notably careful not to endorse any invasion

- It is Washington that should stop taking a dim view of countries with national interests different from its own

Putin, a former Soviet intelligence operative, comes across as a man so manifestly wired for no good that he could make Niccolo Machiavelli look like the second coming of a teenage environmentalist.

That’s the reason I found my way to her tome and started to wonder whether a pessimist might make better sense of what will happen next in Ukraine than an optimist. It turns out that I am not the only reader who found his way to that book.

Not only Nixon could go to China: there’s still hope for Sino-US relations

At the same time, anyone could make the point that, geopolitically, Ukraine is to Russia (more or less) as North Korea is to China. Buffer countries make the nicest neighbours, don’t they? Look at the United States: over Central America, it has insisted on suzerainty consistently since the 19th century. Under the Soviet Union, Moscow had the comfort of Eastern Europe standing by. So why shouldn’t Beijing have big power sway in the South China Sea?

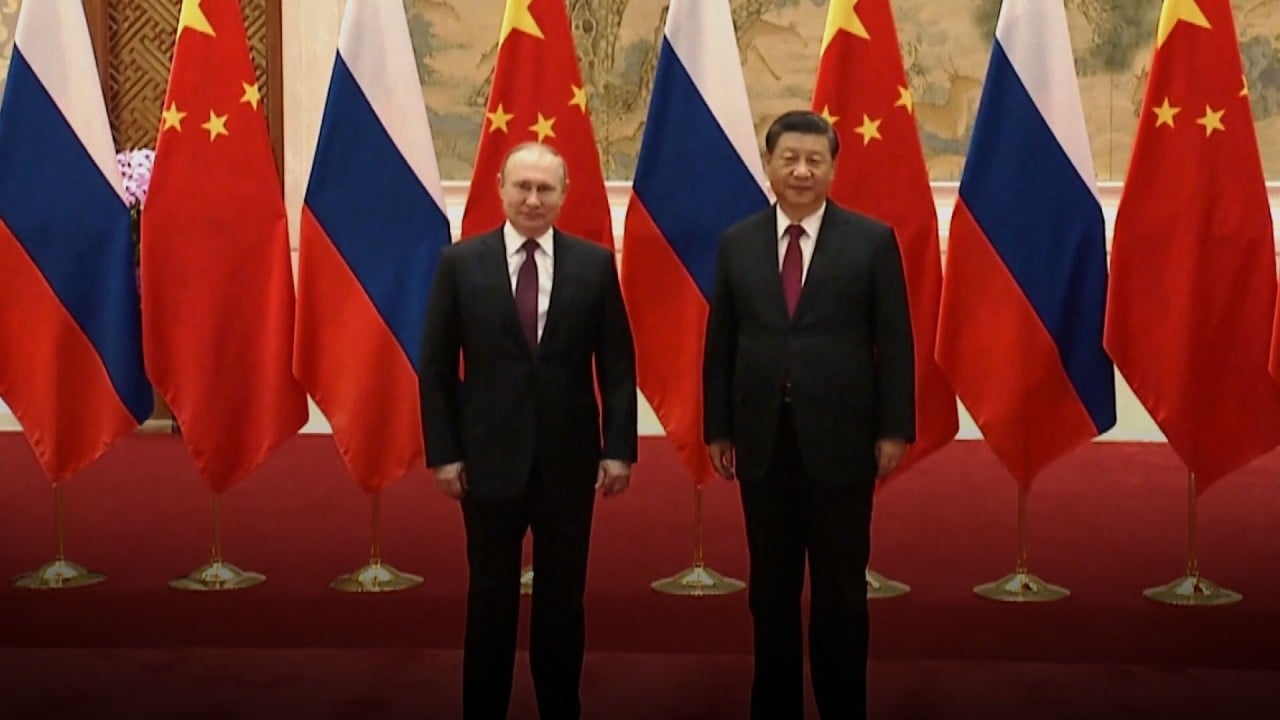

The link between Putin and Xi is less ideological than geopolitical – not global Leninism but time-honoured Machiavellianism. What adds to one’s pessimism is the degree to which the US serves as the convenient focal point for the Russian and Chinese hyper-nationalism needed to rally people.

As long as Washington takes a global policeman’s dim view of countries with national interests different from its own, almost any perceptible difference anywhere could be made into a major issue.

Is it a sign when we find that Germany, which historically should doubt the utility of warfare as much as anyone, is out in front in the anti-war campaign? Last week, Olaf Scholz, Germany’s new chancellor – successor to the extraordinary Angela Merkel – laid it on the line in Moscow when he put it to Putin that today’s leaders have an absolute obligation to avoid war.

Notably, the utopian German philosopher Ernst Bloch (1885-1977) insisted that humanity must live by “the principle of hope” if we are to remain human. But as the negatives pile up these days, only a true optimist can envision a hopeful course. That’s precisely why I stick with optimism, especially for Asia. The alternative is too depressing for words.

Tom Plate, LMU Clinical Professor of Asian and Pacific Studies, is vice-president of the Pacific Century Institute, a non-profit dedicated to peace building between Asia and America