Why Germany’s coalition talks matter for China, Europe and the world

- Three German political parties are negotiating a new coalition, which will have implications for Berlin’s foreign policy

- The recent election indicated a relative political consensus on topics like global warming, but a sharper divergence over China and related human rights issues

The anticipated German “traffic light” coalition – led by the centre-left Social Democrats, with the pro-business Free Democrats and the Greens as junior partners – could soon be driving important policy changes.

While many expect the Greens, who placed third in last month’s election, to make a contribution to sustainability or environmental issues, it could be other issues such as China where they have an unexpected impact.

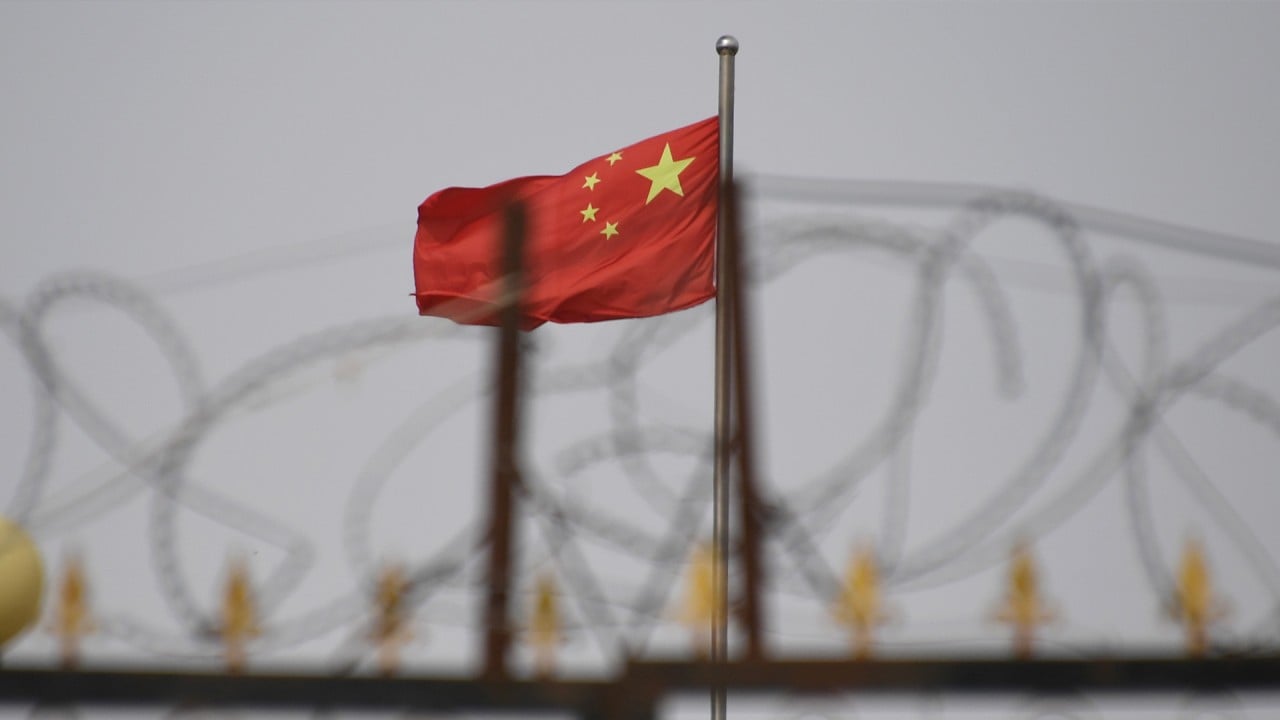

The Greens advocate a more strongly human-rights-centric approach to Beijing. Recently, one of the party’s members of the European Parliament, Reinhard Bütikofer, asserted that, “Germany’s unbalanced China policy [is] heavily skewed towards the interests of a few multinational corporations at the expense of other sectors of our economy, and certainly at the expense of our values and security concerns.”

Beijing regards Merkel as a stabilising ally who helped to counteract the growing number of American and European politicians, including former United States president Donald Trump, who have been calling for decoupling from China.

Why Germany’s post-Merkel shift is no threat to China’s interests

Owing in part to the strong economic relationship between Germany and China, Berlin has traditionally been non-confrontational with Beijing on human rights.

In the years preceding Merkel’s rise to power in 2005, China joined the World Trade Organization; German firms, many of which set up operations in China in the 1970s, profited big time. Since 2015, China has been Germany’s largest trading partner, with the pair exchanging more than US$250 billion in goods in 2020.

China aside, one of the broader concerns held by many about the potential coalition of three, rather than two, parties is that the direction of Germany’s foreign policy will be more contested.

And this after the last decade and a half of Merkel on the international stage, helping to steer Europe through the political and economic tumult, whether it was the euro-zone economic crisis or the more recent migration challenges.

This underlines that, ultimately, Germany’s political flux is not just a domestic issue, but an issue that also matters deeply for Europe, and indeed for the world at large.

Historically, many Germans have been generally content with their post-Cold War lot, seeing themselves as beneficiaries of globalisation. However, this may be changing as shown by the rise of smaller parties with, for instance, the Greens leading polls five months before the recent elections.

Going forward, the nation’s multiparty future may mean that politics will generally be more unstable and less predictable, with an even greater challenge each election cycle to establishing a governing coalition.

Such rotating coalitions could bring problems, including political paralysis and the prospect of the chancellorship becoming weaker, a challenge Scholtz may soon have to contend with if he replaces Merkel.

The nation is now at a historical crossroads. While a multiparty system could have some positives, the political danger is a potentially weaker Germany and Europe in a decade of geopolitical flux and economic uncertainty.

Andrew Hammond is an associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics