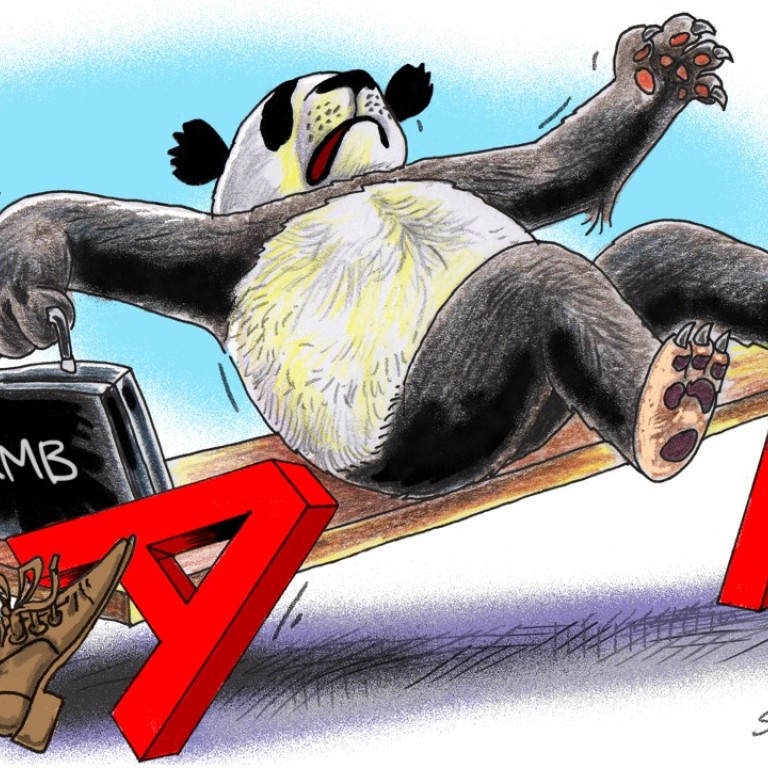

Why is China being penalised for its debt problem, but advanced economies aren’t?

Dan Steinbock says China’s debt-to-GDP ratio is in fact no higher than those of major countries that enjoy a higher credit rating. And unlike these other, more mature economies, China can look forward to years of solid growth

Interestingly, S&P also revised China’s outlook to stable from negative, although ratings cuts usually go hand in hand with a more negative outlook.

Like major advanced economies, China has now a debt challenge. Yet, the context is different, and so are the implications.

Here’s why S&P may be on to something with its cut of China’s sovereign credit rating

In 2008, on the eve of the global financial crisis, China’s leverage – as measured by a ratio of credit to gross domestic product – was 132 per cent of the economy. Even in 2012, it was still barely 160 per cent. Yet, today, it amounts to 258 per cent of the economy and continues to soar. Why has Chinese debt risen so rapidly?

The increase can be attributed to two surges. The first was the result of the 4 trillion yuan (about HK$4.5 trillion then) stimulus package of 2009, which supported new infrastructure but also unleashed a huge amount of liquidity for speculation. Today, the latter is reflected by China’s excessive local government debt (whereas central government debt remains moderate).

China’s mortgage debt bubble raises spectre of 2007 US crisis

China’s leverage is likely to continue to rise, to 288 per cent of the economy by 2021. Nevertheless, the debt-taking is now slowing, which suggests that the central government’s effort to deleverage corporations has started to bite, even before the 19th party congress began.

Nevertheless, there is a degree of double standards in China’s rating cut. Ratings agencies punch emerging economies around, but treat advanced economies with silk gloves.

China’s uneasy relationship with foreign credit ratings firms

When China’s leverage is reported internationally, it triggers much concern about the future. Indeed, that leverage (258 per cent of GDP) is higher than that of emerging economies overall (189 per cent). But is the latter still an appropriate benchmark? After all, most emerging nations are still industrialising, but China is shifting to a post-industrial society. That’s the goal of the rebalancing of the economy from investment and net exports to consumption and innovation.

How China’s billion savers embarked on a household debt binge

By contrast, advanced economies’ leverage – at 268 per cent of GDP – exceeds that of China. While the ratio of the US (251 per cent) is close to that of China, those of the UK (280 per cent), Canada (296 per cent) and France (299 per cent) are significantly higher. Yet, the credit ratings of these advanced economies – Canada (AAA), US (AA+), France (AA) and the UK (AA) – are substantially better than that of China (A+).

The ratings agencies appear to presume that the outlook of advanced economies is more stable than that of China. But is it?

In advanced economies, total debt has accrued in the past half a century, decades after industrialisation. In these countries, the accrued debt is the result of high living standards that are no longer sustained by adequate growth and productivity. So leverage allows them to enjoy living standards they can no longer afford.

Moody’s downgrading of China’s credit rating is without basis amid ‘new normal’ in the economy

An even more interesting example is Japan, whose leverage is one of the highest in the world (373 per cent). While that rating is much higher than China’s and continues to soar, thanks to record-low interest rates and massive monetary injections, Japan’s current credit rating is A+, the same as China’s.

Is Japan’s long slump finally ending?

The context of leverage is very different in China, where excessive debt was accrued only in the past five years, not in the past 50 years as in most advanced economies. And unlike the latter, different regions in China are at different stages of industrialisation. Meanwhile, intensive urbanisation will continue for another decade or two, which ensures solid growth prospects.

However, due to differences in economic development, Chinese living standards remain significantly lower relative to advanced economies’. Nevertheless, they will double between 2010 and 2020, due to solid growth outlook and rising productivity.

In advanced economies, debt is a secular burden; in China, it is a cyclical side-effect. Yet, China has been penalised with a lower credit rating, but not the advanced economies, which suffer from secular stagnation and have little hope of reducing their debt.

Indeed, the central government’s efforts to rein in corporate leverage could stabilise the prospects of downside financial risks by the early 2020s. Yet, even then, credit growth will remain at levels that increase financial stress over time.

What is even more problematic is that, after the next five years, advanced economies will face a far greater leverage distress.

That’s precisely when ratings agencies’ double standards will come back to haunt them, as secular stagnation deepens in advanced economies.

Dr Dan Steinbock is founder of the Difference Group and has served as research director at the India, China and America Institute (US) and visiting fellow at the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Centre (Singapore). See: www.differencegroup.net