Why economic reforms in China mean a bigger role for the state

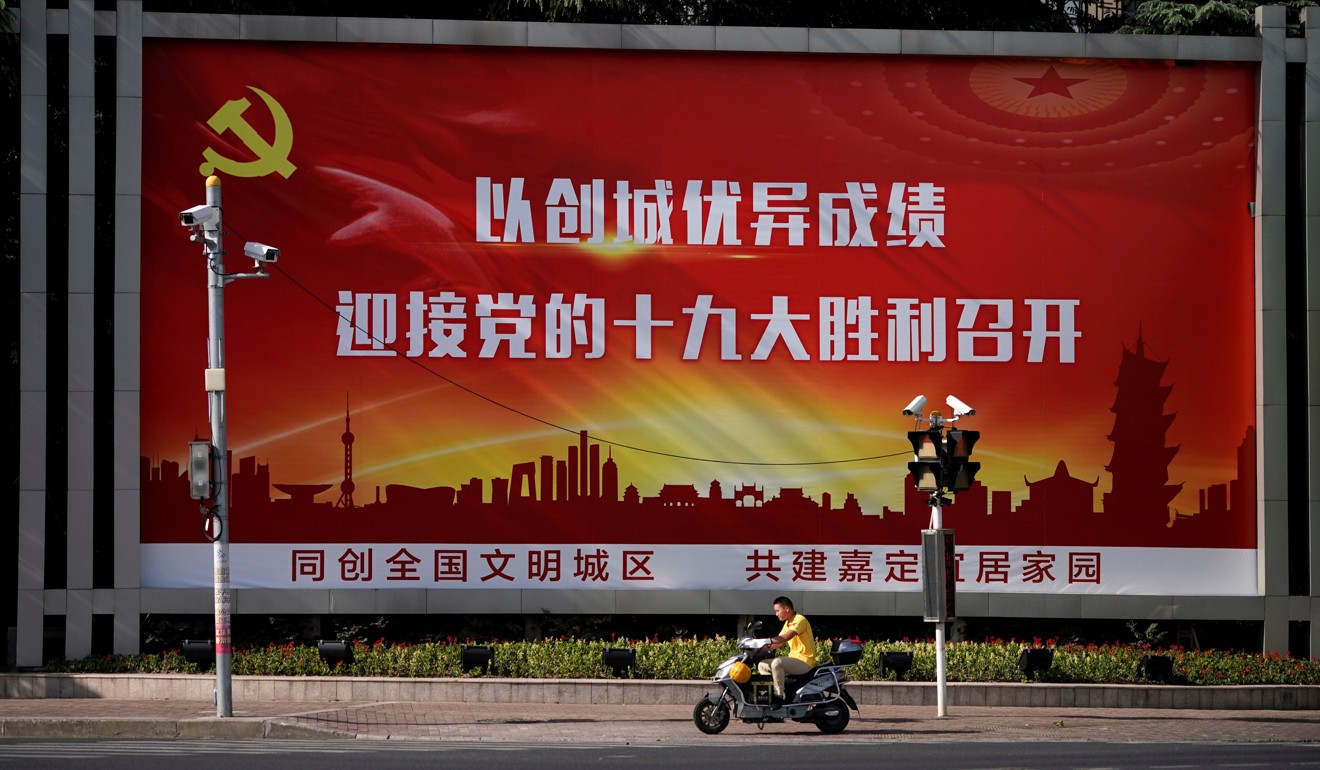

Max Zenglein says under Xi Jinping, the state’s role in economic planning has only increased, and signs point to more controls being announced at the 19th Party Congress, rather than liberalisation, given that national interests take precedence over market principles

Rather than breaking up state monopolies, China’s reforms of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) focus on mixed ownership and public-private partnerships. The idea is to bring in private companies to help transform SOEs into financially sound, innovative and internationally competitive national champions.

In this process, the country’s private tech giants are particularly vulnerable to more government influence. Sectors such as artificial intelligence, big data, digital payment systems and industrial robots are seen as crucial building blocks for establishing China’s global technological leadership. Now that their products fall in the range of national strategic economic interests, they are at risk of closer state entanglement.

Xi Jinping’s political thought will be added to Chinese Communist Party constitution, but will his name be next to it?

Another prominent example is an ongoing effort to establish party committees in private, even foreign-owned, companies. Once established, these committees may influence management decisions towards pursuing national targets.

It will be harder to evaluate the competitive landscape in China as lines between policy-driven and market-driven forces blur. Foreign companies will be ill prepared to face growing Chinese competition at home and abroad – just as more liberal economies struggle to respond to China’s state-led forays into their markets.

China’s leaders do not plan to withdraw state influence from the economy. Political stability and the pursuit of national interests take priority over market principles.

Max J. Zenglein is an economist at the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin