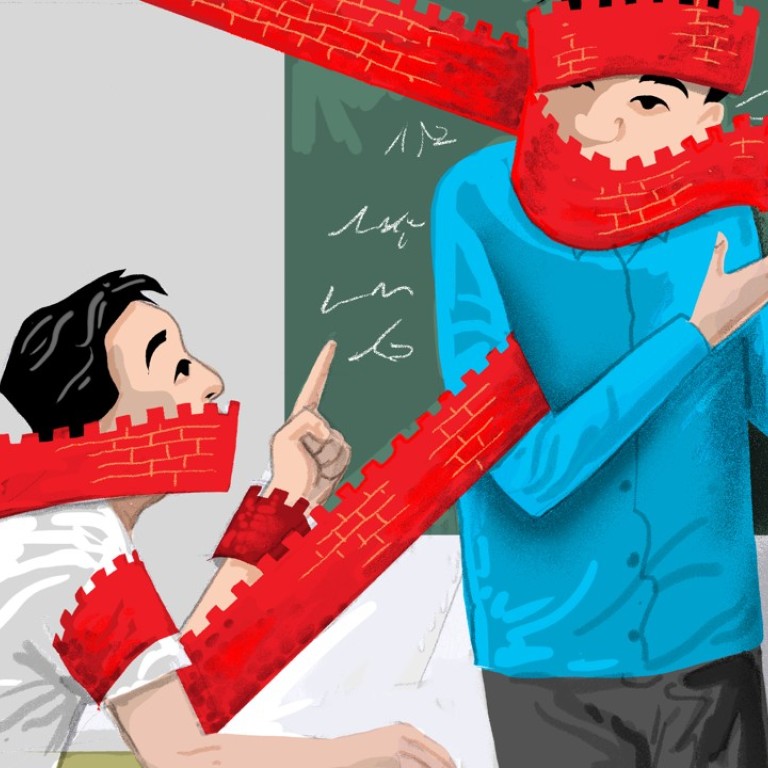

As Communist Party censors ban all criticism in China’s classrooms, what remains?

Audrey Jiajia Li says the Chinese ‘rectification campaign’ to ensure ideological purity is being exported beyond its borders, and is a cause for concern in being reminiscent of Mao-era zealotry

The move triggered sharp criticism worldwide, mainly because such a reputable Western publisher had gone this far to bow to pressure for accessing the Chinese market, and that China is now exporting its notorious censorship.

Bravo to Cambridge University for its U-turn on China’s censors

To those familiar with the status of academic freedom in China in recent years, this came as no surprise. This year alone, scores of professors have been sacked as a result of their online views. Li Mohai, for example, a faculty member at the Shandong Institute of Industry and Commerce, was the victim of a tip-off and lost his post because of his tweet: “‘People’ is a political term while ‘citizen’ is a judicial one. When you are willing to be a slave, you are just one of the ‘people’; but once you want to become a citizen, you might already be labelled as the enemy of the people”.

The Chinese authorities often cite “public safety” concerns over such online expressions. But if a teacher keeps his or her mouth shut online, is that the safer option? Not really.

What was China’s Cultural Revolution?

The “rectification campaign” began in late 2014, when the Liaoning Daily, a provincial party mouthpiece in northeastern China, ran an open letter accusing university lecturers of lacking ideological loyalty and being excessively negative about the country. The newspaper claimed that upon receiving a student’s complaint about having “heard a lot of negative things in her classroom”, it sent dozens of “undercover reporters” to 12 colleges in five cities to audit the situation. They concluded that scholars, especially in the social sciences, were inclined to “denigrate China’s image”. The article sent a chilling warning to the lecturers, demanding “objectivity” and a focus on the “bright future”.

Xi calls for more thought control on China’s campuses

When students are encouraged to snitch on their professors for “improper discussions” in class and professors are concerned about possible government monitors in the audience, the atmosphere in the classroom can hardly be conducive to great thought.

China-India border dispute spills over into Australian university

This awkward mix of ideological and academic language generates concern, as they are reminiscent of the political zealotry of the Mao era, when it was common to see headlines like “Undefeated Mao Zedong thoughts guide me to becoming a good butcher” and “Using Mao thoughts to cure mental illness”.

Audrey Jiajia Li is a freelance columnist and 2017 Elizabeth Neuffer fellow at MIT