Hong Kong’s legal system is undergoing ‘nationalisation’, and the opposition must realise this

Tian Feilong says opposition lawmakers’ protests against the disqualification of their peers are misguided, as the case has strengthened the rule of law in Hong Kong and shows increased integration with the Chinese legal system

Second, the opposition camp have themselves used Hong Kong’s independent judiciary and the rule of law as political tools to challenge and interfere with government policy, abusing the right to judicial reviews. Their demands are not entirely based on a wish to protect the rule of law.

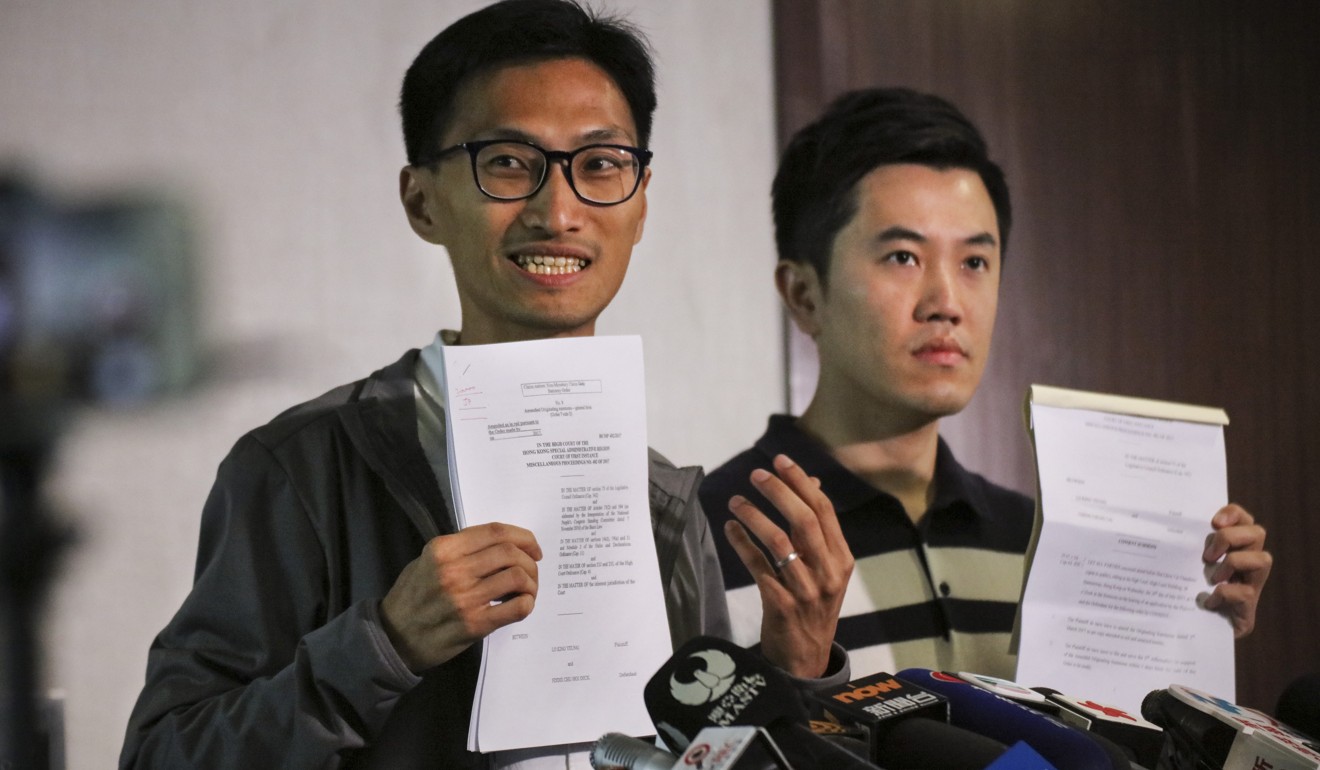

Oath-taking antics: The acts that got six Hong Kong lawmakers disqualified

In fact, the disqualification case has strengthened the rule of law in Hong Kong, allowing national interests to be gradually included as part of jurisprudence. The case also shows that the common law of Hong Kong is being fine-tuned, improved, and integrated into the Chinese legal system step-by-step.

Watch: Four more lawmakers disqualified over oath-taking

Since the handover, the rule of law in Hong Kong has been maintained and developed according to the common law tradition and under the Basic Law. However, since the change of sovereignty, the original common law system of Hong Kong and the characteristics of its legal system have been undergoing a process of “nationalisation”. The opposition has been resisting the trend, as seen in their attitudes towards interpretations of the Basic Law, and has made use of two political agendas to maintain and strengthen Hong Kong’s “quasi-fully autonomous” status.

Governing Hong Kong according to law is not equal to, but higher than, a high degree of autonomy

The political positioning of this “quasi-complete autonomy” does not comply with the original intent of “one country, two systems”. It may even cause institutional damage to Basic Law principles, such as national sovereignty, security and developmental interests. In order to restrict and balance such political movements aimed at achieving “quasi-complete autonomy”, the National People’s Congress has resorted to institutional tools, such as interpreting the Basic Law.

Beijing ‘would not hesitate’ to interpret Basic Law if Hong Kong hurt by Legco filibustering

Beijing is increasingly focused on “administering Hong Kong according to law”. That is based on the characteristics of “one country, two systems” and of Hong Kong as a society governed by law.

The principle of governing Hong Kong according to law is not equal to, but higher than, a high degree of autonomy. It is the main way for Beijing to fully and accurately implement “one country, two systems”. A high degree of autonomy is a part of the rule of law. By institutionalising its governing powers, Beijing can have grounds for normalising its governance of Hong Kong in accordance with law. This was not prominent in the past 20 years, but will be in the future.

Watch: Hong Kong – 20 years in four minutes

More Hong Kong pan-democrats in ‘highly risky’ position after ouster of four lawmakers

The rule of law is conservative and cannot serve simply as a supporter for ‘adversarial politics’

Such a shift in the rule of law in Hong Kong has surprised the opposition camp, but is inevitable.

First, the rule of law is conservative and cannot serve simply as a supporter for “adversarial politics”.

Third, the NPC interpreted the Basic Law based on the intent of legislation and the will of the country. Statutory bodies must follow and apply the interpretations, and this is part of the spirit of the rule of law.

Tian Feilong is an associate professor at Beihang University’s Law School in Beijing, and a director of the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies