Copyright bill is no ‘Article 23 of the internet’

Danny Friedmann says neither the original ordinance nor the proposed bill carries provisions that stifle freedom of expression or creativity, as critics fear, and the city must be encouraged not to follow outdated laws

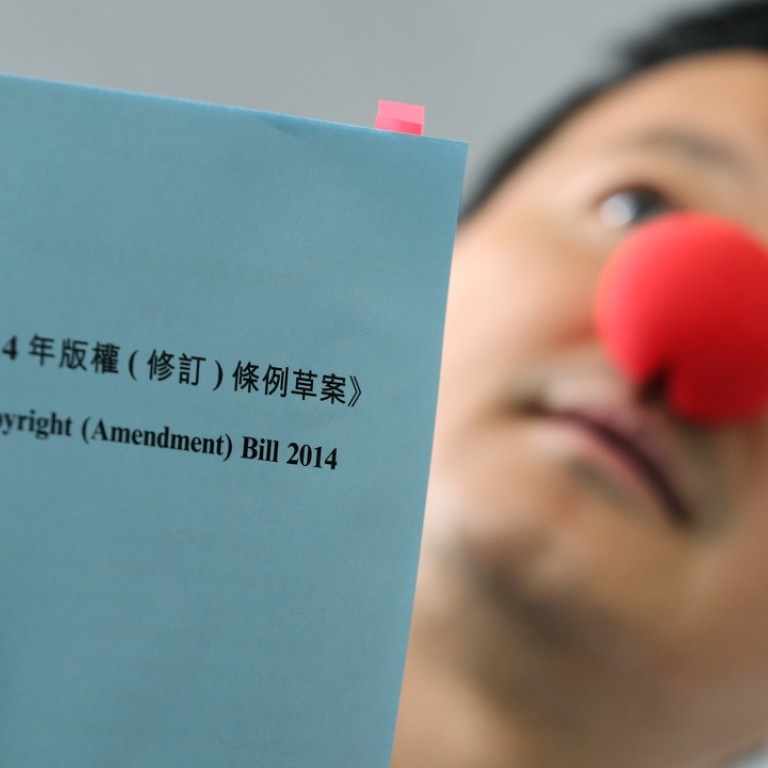

As a researcher of intellectual property law, it makes my heart rejoice that the general public passionately takes notice of a copyright amendment bill. However, what surprises me is the demonisation of the existing copyright ordinance in favour of the Copyright (Amendment) Bill 2014. At the same time, I do not understand the framing of the bill as the Article 23 of the internet.

READ MORE: Fair use or fair dealing? Here’s a fair case for postponing Hong Kong’s new copyright law

I do think that the amendment bill misses some opportunities to make it future-ready, but it is difficult to see why the bill would stifle creativity or freedom of expression. I would argue the opposite.

Let us first quickly review the existing law: A Post editorial last week ominously warned that it “should be noted that if the law is rejected, the proposed safeguards for freedoms will also lapse. This means some draconian provisions in the existing law will continue to apply. Opponents should therefore think twice.”

The old law was not that bad, and the new bill is not that good. But both do not actually harm freedom of expression

However, it remains unclear to which “draconian provisions” it referred. The existing law applies its fair dealing tests to exempt from copyright infringement use for the purposes of “criticism, review and news reporting”, and “research, private studies, education and public administration”. One can argue that the use of a copyrighted work for the purpose of parody already falls within the category of criticism.

Then, courts apply the fair dealing factors, such as the purpose and nature of the use (whether the work is used in a commercial way), the nature of the work (whether the work is more factual or creative, and already published or not), the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the whole copyrighted work, and the effects of the use on the value of the copyrighted work.

READ MORE: Pan-dems’ proposed changes to Hong Kong copyright bill too broad, says Anthony Tong

In comparison to the existing copyright ordinance, the amendment bill expands the exemptions of copyright infringement with the more explicit categories of “parody, satire, caricature, pastiche” and “comments on current events, and quotation”. This expansion does not harm, but harnesses, freedom of expression. The same fair dealing factors apply as in the existing law.

The courts in Hong Kong have interpreted fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression, in a generous way

An extra category to exempt predominantly non-commercial user-generated content from copyright infringement, following the Canadian example and advocated by concern group Keyboard Frontline, is in fact a modest extension. In practice, user-generated content is created on social media, where contractual relations rule supreme. Therefore, copyright exemptions can have less influence on social media, because of pre-upload filtering. By using this technology, online service providers avoid being overwhelmed by copyright holders’ take-down requests and being sued by them. It also prevents internet users from being held liable for copyright infringement.

Hong Kong does not have to follow outdated laws but can make use of the “law of the stimulative arrears”, and leap forward. Each provision of a bill should be judged in light of the incentives it is providing to the creation of original and derivative works.

The old law was not that bad, and the new bill is not that good. But both do not actually harm freedom of expression. The courts in Hong Kong have interpreted fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression, in a generous way. One can always ask permission from the copyright holder, and otherwise one can transform the primary work to such an extent that a new work is created. Freedom of expression, the lifeblood of society, does not mean a premium on a lack of creativity.

Dr Danny Friedmann is a researcher and lecturer at the Faculty of Law, Chinese University of Hong Kong