Noble Group’s amazing story of how to soar, then fall back to Earth

Commodity trader Noble Group, helmed for many years by Richard Elman, is among the great corporate tales of shifting fortunes in recent years

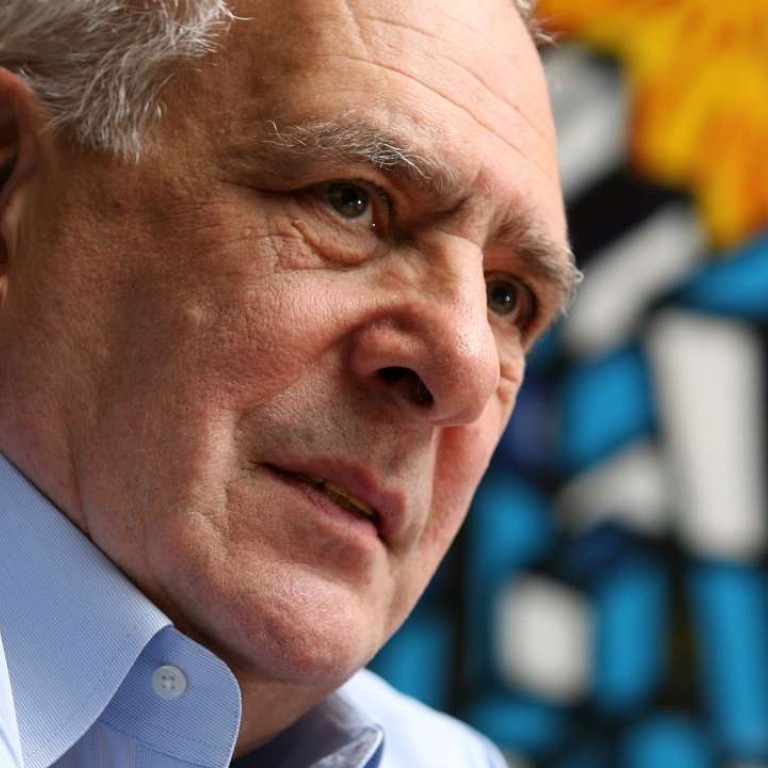

When I first arrived in Hong Kong I kept hearing great things about a company formed in 1986. The company was called Noble and its CEO, Richard Elman, was widely regarded as a genius. He built the Noble Group into being one of the world’s biggest commodity traders but now its very survival is in question.

This is a classic tale of smoke and mirrors, hubris and denial. In a different world it might be possible to say that lessons will be learned from Noble’s demise but then again that’s what we were told after Enron’s collapse in 2001. By no coincidence Enron’s business model was very similar to that of Noble, except that Noble has not yet filed for bankruptcy.

Noble, like Enron, had a great story to tell. True, no one outside the company was exactly sure how it made money but the proof seemed to be in the pudding as its share price rose and rose again. The heady rise in its market capitalisation was frequently punctuated with news of acquisitions and fabulous deals; only wimps questioned how they were leveraged.

When Noble, founded in Hong Kong, made its move to Singapore, there were strenuous efforts to keep it here. Some of the biggest names in banking and accountancy joined Noble’s cheerleaders and quite respectable analysts and other commentators joined the chorus. Today, unsurprisingly, they are all suffering from acute amnesia. Some, however, claim not to have forgotten but are bitterly accusing Elman and his colleagues of misleading them. Others, with the benefit of hindsight, are busy claiming a degree of foresight that they remarkably kept under wraps.

Somewhere in all this was genuine business genius, yet what really mattered was the Noble story which, in essence, was: loads of money could be made from trading commodities, many of which are in short supply and all it needed was for the smartest kids on the block to find a way of skewering the best deals and then moving on to skewer yet bigger and better deals.

When the shine came off commodities as the price of products like coal and oil plummeted, a frisson of unease spread among investors. Yet Noble cheerfully assured them that lower prices also meant greater opportunities.

However in February 2015 a small outfit called Iceberg Research produced a report that made a pretty good job of showing that the emperor had no clothes. The crux of its findings were that in the past five years Noble had been reporting higher net profits than the sums it was generating from cash sales.

This was followed by trenchant rebuttals from Noble, litigation against the research company and the usual questioning not so much of the report’s facts but of the motives of those purveying the information, accompanied by sniffy questioning of why a previously unknown outfit was in any position to understand or comment on the business of a mighty company like Noble.

However the facts had a nasty way of not disappearing as the share price plunged and plunged again. Investors, who had been quiescent in not demanding information about Noble’s business decided that the time had come for far more disclosure.

Digging deeper in its hole Noble promised greater transparency but said it would be circumscribed by the need to retain confidentiality over its trading methods because much of this could impact on its ability to conduct business. Then executives started deserting the sinking ship and last February Nobel was forced to disclose a massive loss. It was then discovered that its net debt amounted to some US$3.7 billion compared with a market capitalisation of just over US$1 billion.

This was followed by announcements of asset disposals and job cuts and a promise that Elman would step down as Executive Chairman within a year. On the way Noble was kicked out of the Straits Times Index and there were a flurry of brokerage reports bearing a clear “keep away” message. A knockdown rights issue, aimed at eradicating some of the debt, only succeeded in further depressing the share price. In other words it was a case of too little, too late.

Earlier this year Elman insisted that Noble would carry on and that the company would be run “as good as any other company is run”. His protestations would have fallen on sympathetic ears when Noble was riding high but markets are cruel places and once it is widely perceived that the story has changed it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to get back to the original tale.

Noble enthusiasts failed to apply the smell test; it didn’t smell right because so little about its activities added up. This is not the first, nor the last time for the smell test to be ignored.

Stephen Vines is a Hong Kong broadcaster, writer and entrepreneur